June 04, 2018

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris/Public Domain

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris/Public Domain

This painting depicts Blackbeard being captured in a 1718 battle. The famed pirate terrorized the Philadelphia region in 1717, when he captured six or seven merchant ships in the Delaware Bay.

Benjamin Franklin once described a scene that left the young printer quite bewildered.

Fueled by "a vain hope of growing suddenly rich," Franklin wrote in 1729, many early Philadelphia residents had taken to searching for buried treasure "almost to the ruining of themselves and families."

Laborers and crafters could be seen wandering through the woods by day and returning there at night – only to be spooked by fears of "malicious demons" guarding the treasures.

"This odd humor of digging for money, through a belief that much has been hid by pirates formerly frequenting the river, has for several years been mighty prevalent among us," Franklin wrote, "insomuch that you can hardly walk half a mile out of the town on any side, without observing several pits dug with that design, and perhaps some lately opened."

Franklin penned those words in 1729, as the so-called "Golden Age of Piracy" was drawing to a close.

But Philadelphia – founded by William Penn in 1682 – was a hotbed for pirates in its early years, when some of the most notorious pirates freely roamed city streets. And tales of buried treasure quickly became part of local legend.

"There were pirates on the Delaware River," said Craig Bruns, chief curator at the Independence Seaport Museum. "We're talking in the 1700s, before the creation of the country. ... Because Philadelphia is the largest port in the colonies at the time, it attracts a lot of commerce."

As dozens of merchant ships headed toward the West Indies each year, that commerce caught the eyes of pirates. With Philadelphia lacking naval protection, pirates could intercept the merchant ships and steal commodities to resell elsewhere.

"Yes, they would get some gold here and there," Bruns said. "But it was more about basic commodities that they could resell."

It did not hurt that many city leaders, including Gov. William Markham, sympathized with the pirates who frequented the city's taverns and conducted business in its marketplaces. Though Markham publicly denied associations with pirates, his daughter was married to wanted pirate John Avery.

Even those who railed against piracy were not always practicing what they preached.

The Rev. Edward Portlock, the rector at Christ Church, agreed to hide some 600 pieces of gold handed to him by Robert Bradenham, a physician to the famed Capt. William Kidd. Portlock, who decried piracy from the pulpit, hid the pirate treasure beneath the church floor.

But Portlock's secret was uncovered, leading to Bradenham's arrest. And Bradenham flipped on Kidd, serving as the primary witness at the pirate's trial in London.

Kidd, once a privateer, denied the accusations of piracy. But he was found guilty of murder and piracy and was executed in 1701.

Nearly two decades later, another famed pirate had Philadelphia business leaders in a tizzy.

Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, appeared off the mid-Atlantic coast alongside Stede Bonnet in the summer of 1717, effectively scaring off commerce.

Blackbeard, who reportedly had visited Philadelphia two years prior as a mate and likely had family here, stationed his ship, dubbed "The Queen Anne's Revenge," in Delaware Bay.

The waterway provided ample places for him to ambush merchant ships, according to Arne Bialuschewski, who detailed Blackbeard's movements – and the campaign against him – in the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography:

"During the peak years of pirate activity off the North American coast in the summer and fall of 1717 and 1718, several vessels from Philadelphia were captured by Blackbeard and Bonnet's marauding gang. However, the surviving evidence makes it easy to overestimate the losses. The number of vessels lost to pirate attacks, either through theft or destruction of a prize, appears rather small. More important was the fact that local shipowners were frightened by Blackbeard and his fellow pirates."

By October, Blackbeard had captured six or seven ships, prompting statesman James Logan to inform New York and New Jersey Gov. Robert Hunter of the problem, noting that many of the pirates were familiar with Philadelphia.

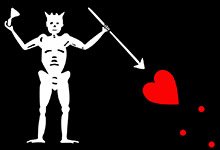

Blackbeard's Jolly Roger flag depicted a skeleton piercing a heart, whilst toasting the devil. This illustration is from an image in 'Blackbeard the Pirate' (2007) by Angus Konstam.

The news spread throughout the colonies. A newspaper account from Philadelphia, published in the Boston News-Letter, detailed the seizures, detailing the ship's weaponry and the pirates' treatment of passengers and cargo:

"They have arms to fire five rounds before load again. They threw all Codds Cargo over board, excepting some small matters they fancied. One Merchant had a thousand Pounds Cargo on board, of which the greatest part went over board, he begg'd for Cloth to make him but one Suit of Cloth's, which they refus'd to grant him."

Seeking an end to the disruption in trade, the British government offered amnesty to any pirates who surrendered to colonial officials. Pennsylvania Gov. William Keith also offered an award to anyone who discovered pirates who chose not to surrender.

With winter approaching, Blackbeard steered his ship south, possibly pillaging ships in the Caribbean Sea before eventually accepting amnesty in South Carolina. It was short-lived.

By May 1718, Blackbeard had returned to sea, stationing his ship off the coasts of the Carolinas. Three months later, Keith issued a warrant for his arrest in Philadelphia.

An arrest was never made. A naval force killed Blackbeard in North Carolina, with the pirate's head famously being carried off to Virginia. A South Carolina militia captured Sted Bonnet, who was hanged.

“The Pirate's Ruse: Luring a Merchantman in the Olden Days” by is a 19th-century interpretation of pirates attempting to lure in a ship so they can board it.

But the legend of Blackbeard and tales of buried pirate treasure continued to grow through the ensuing decades.

An 1846 book containing historical collections from New Jersey, tells of two haunted trees in Burlington County, including one large black walnut tree known as "Pirate Tree."

Blackbeard and his associates allegedly buried silver and gold there, doing so in silence on a stormy night. The legend claims a Spaniard, known for being a reckless outlaw, offered to guard the treasure by surrendering his life.

"He was shot through the brain by Blackbeard, with a charmed bullet, which penetrated without occasioning a wound, thus leaving him as well prepared as ever for mortal combat, except the trifling circumstance of his being stone dead," the historical collection states. "He was buried in an erect position; and so well has he performed his trust, that, for any evidence we possess to the contrary, the treasure remains there to the present day."

There are countless tales of pirate treasure buried throughout the Jersey Shore, and even in Pennsylvania, said Dan Rolph, a historian at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The treasures often allegedly belong to the most famous pirates – Blackbeard or Kidd – and are protected by spirits. But such tales involve a motif that dates back well before Blackbeard terrorized the Atlantic, Rolph said.

"This belief of treasure and spirits goes way back into early medieval literature, belief and superstition," Rolph said. "So it's not just something that came around in the 18th century, or is a product of Hollywood. This is something that's been with us as a culture for centuries."

But that doesn't mean pirates – or other people – didn't bury treasure. In fact, plenty of people have found pots of gold or coins buried in the ground.

"We have actual, literal documentation that piracy was a big problem in this area," Rolph said. "To then also have local legend to support the burial of treasures, I don't think, is beyond the imagination.

"Now whether all the legends are true, of course, no. There's all kinds of ... poetic license that's come in. But that doesn't in any way negate the story or negate examples of actual treasure that has been found."

So maybe Ben Franklin shouldn’t have been griping about those early Philadelphians after all.

Source/Public Domain

Source/Public Domain Source/Library of Congress

Source/Library of Congress