July 28, 2015

We all age, whether we like it or not.

The eye creams, serums, antioxidant pills, and so-called “superfoods” we throw our money at supposedly slow the process down — but even a legitimate anti-aging product would only delay the inevitable.

Getting older affects every part of the body. Along with the visible changes, like white hair and wrinkles, bones shrink and become less dense, muscles lose their strength and flexibility, and our brains aren't as sharp or quick to react anymore. Psychologically and socially too, time takes its toll on us — living with new physical limitations isn't easy, and there's a greater likelihood of family, friends, or spouses passing away.

“There's another way to think about aging, and it's based on evolutionary theory,” Johnson said. “We age because there's no strong reason to not age – it's happening sort of by accident.” – F. Bradley Johnson, Fellow at Penn's Institute on Aging.

Why does this happen to us? Do our bodies simply start to break down after awhile from general wear and tear, like an old pair of shoes? In a mechanistic sense, this is more or less correct.

“The simplest way to think about aging is that your cells and tissues are constantly being damaged: oxygen that is necessary for life has the side effect that it can damage molecules, toxins in our food, radiation coming from sunlight — things you can't avoid,” said F. Bradley Johnson, associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and Fellow at Penn's Institute on Aging.

Aging is a consequence of this type of damage building up within our bodies over time. Every unintentional break in DNA, misfolded protein, or cell that doesn't divide properly adds up year after year, eventually leading to overall deterioration and, possibly, disease.

But this decline also happens because, as humans, evolution dictates that we aren't really meant to live longer than the seventy-odd years our bodies last. In other words, the average human life span is sufficiently long enough to fit in all the reproductive and parental duties necessary to pass on our genes.

“There's another way to think about aging, and it's based on evolutionary theory,” Johnson said. “We age because there's no strong reason to not age — it's happening sort of by accident.”

The energy required to maintain a longer life span in the face of accumulating damage to cells and tissues would perhaps be too great and without any added benefit to the species. So instead, we hand down our genetic material and wisdom to offspring as a sort of reboot.

Nevertheless, research has shown that aging — at least in animals — can be manipulated to a certain extent. Studies on worms, mice, and monkeys have found that life span and health span may be extended with certain drugs or lifestyle practices.

Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, believes that delaying aging is the best way to hold off disease. He is currently planning a clinical trial called Targeting Aging with Metformin (TAME) to see if the antidiabetes drug can stall the onset of disease, and ultimately death.

“What do people in the U.S. die from? Heart disease, cancer, stroke, infectious disease, neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer's,” said Johnson. “Aging is the major risk factor for all of these diseases. If we could target the underlying aging process, we would simultaneously alleviate all of these disease at once.”

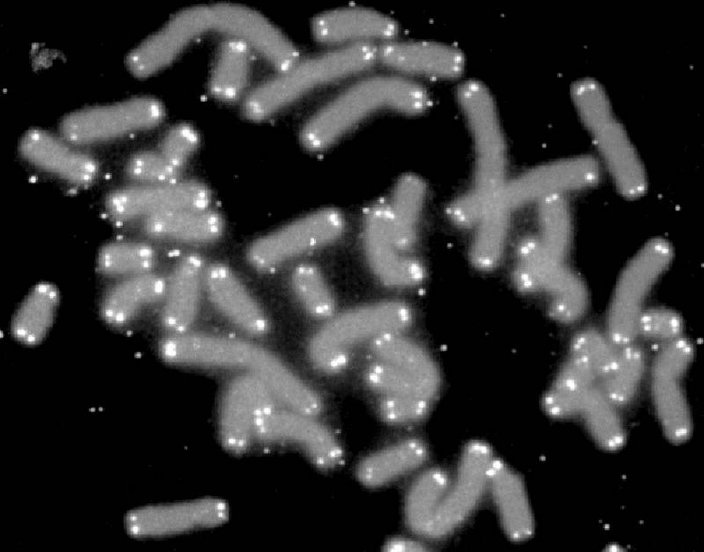

Johnson's own research focuses on telomeres, the protective structures at the end of chromosomes, which appear to be an important component to aging. As cells divide, telomeres get shorter — but they are also shorter in cells at risk for cancer, so there could be some net benefit for the decrease in length. But cells with short enough telomeres are no longer able to divide. His lab explores ways in which telomeres might be maintained or repaired.

And last year, three studies were published simultaneously on the regenerative effects of blood from young mice given to elderly mice. When given injections of young blood or a special protein found within, their stem cell activity in muscle and brain saw a boost. For the next few weeks, the elderly mice could perform better on strength, endurance and memory tests.

The first young blood clinical trial, taking place at Stanford University, is currently recruiting subjects with Alzheimer's disease to see if a transfusion of blood plasma from people younger than 30 will improve their cognitive function.

Until science or technology finds a way to halt the process completely, we will have to accept aging as part of our lives.

Albert Finestone, the former director of Temple University School of Medicine's Institute on Aging, recommends keeping the mind active, a proper diet, and regular exercise. At 94 years old, he knows that his body isn't what it used to be, but he still reads the news daily, uses an exercise bike, and keeps frequent contact with his children and grandchildren.

Finestone emphasizes things like getting the right vaccines and preventing injuries if possible. But most of all, it's important to express gratitude and value what life has given you.

“Happiness is an ephemeral kind of thing,” he said. “The best thing is not to be happy, but to be satisfied and to be honorable — to do the honorable thing, be satisfied with what you've achieved, and don't take any shortcuts with morality.”