January 12, 2024

Wikicommons/Clark Art Institute

Wikicommons/Clark Art Institute

Possessing hair from a friend or loved one was common in the 18th and 19th centuries. More than 100 U.S. institutions claim to have samples of President George Washington's hair. The Museum of the American Revolution is among them.

Picture a portrait of George Washington. He's probably looking a bit severe, back straight and lips drawn in a stiff line. His coat is dark, his cheeks likely flushed. And his hair is always a wispy white, curled just above his ears.

There's nothing especially remarkable about this hairstyle. Many of America's Founding Fathers sport a version of it in their own portraits, with slight adjustments for length, texture or hairline. But Washington's hair was once so prized that it sparked its own cottage industry, fueled by mourners of the nation's first president and grifters trading on the family name.

According to a map maintained by historian Keith Beutler, over 100 institutions in the U.S. boast bits of Washington's hair, with most of the tresses concentrated along the East Coast. (The former president's home at Mount Vernon has more than 50 samples alone.) One of those locks is currently housed in the archives of the Museum of the American Revolution, the Old City institution that opened in 2017.

"Washington, during his lifetime, sometimes gave people hair," Aimee Newell, the museum's director of collections and exhibitions, explained. "Because hair is part of you that doesn't disintegrate when you're gone. So it was very meaningful and it was a memory for people to share between themselves. There was no camera to take pictures."

While treasuring a piece of your friend's hair might seem creepy now, it was a common custom in the 18th and 19th centuries. The locks could be kept in a decorative box or placed in a ring, brooch or locket. "Hair jewelry" got incredibly elaborate, featuring braids and curls bound by pearls or sculpted into flowers.

In Washington's America, it was perfectly normal to gift someone your hair even while you were still alive. When he was living in Philadelphia — the nation's original capital — the Founding Father presented his secretary of treasury Oliver Wolcott and Wolcott's wife Elizabeth with a trimming encased in a locket as a "memorial to the General."

After Washington's death in 1799, however, interest in his hair skyrocketed. The vast majority of presidential locks circulating today, Newell said, were collected shortly before Washington's burial.

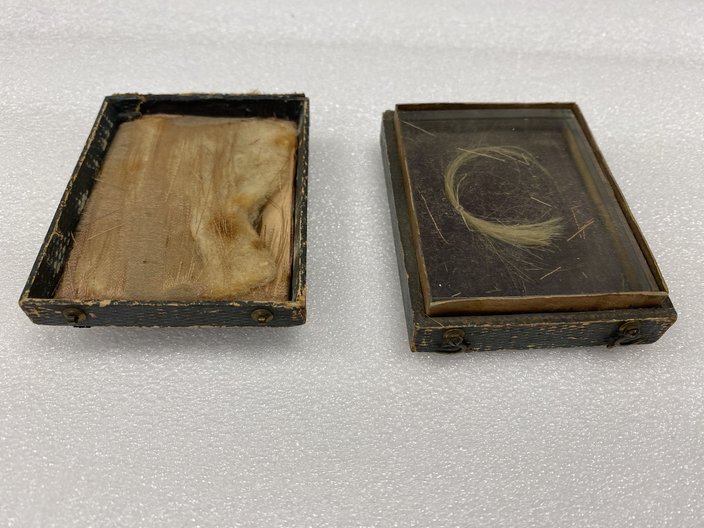

The Museum of the American Revolution's lock of George Washington's hair is stored in black box with a simple gold leaf pattern, tucked away inside its Old City archives.

"I kind of am afraid he went to the grave bald," she joked. "That's really, I think, when they cut a number of locks off."

Washington's secretary Tobias Lear fielded requests for and distributed the hair to admirers across America. One such request came from Elizabeth Wadsworth, the daughter of Revolutionary War veteran and politician Peleg Wadsworth, who begged her father for a keepsake in a letter written weeks after Washington's death.

"Papa I will tell you what I want — more than any thing I think of at present — it is a scrap of General Washington's hand writing, perhaps his name," she wrote. "I should think you might obtain it without any difficulty, and I should value it very highly. Papa had he hair? A lock of that I should value more highly still."

Wadsworth's pursuit of a presidential memento reflects the intense national mourning over Washington at the turn of the century. Upon the announcement of his death, Congress immediately adjourned and got to work planning the country's first true state funeral. The national procession took place in Philadelphia on Dec. 26, 1799, and featured two troops of horses carrying flags, as well as an hour-long gun salute.

"I think it says the most about how people felt when he died, and the stature he had in America," Newell said. "There was this tremendous outpouring of grief."

As distraught Americans clung to scraps of their first president and wartime leader, some enterprising individuals saw an opportunity. Forgers like Robert Spring, an Englishman who moved to Philadelphia in 1858, began signing books and penning letters as Washington and then selling the items to collectors. Even later in the 1910s and 1920s, William Lanier Washington — a descendant of Washington's half-brother Augustine — held several auctions of buckles, buttons and other knickknacks that supposedly belonged to his famous ancestor. While some are considered authentic, Newell recalls at least one story of Lanier Washington selling off a one-of-a-kind Washington keepsake that turned out to be fraudulent. When the buyer confronted Lanier Washington, the tale goes, the man was so furious he dropped dead of a heart attack .

"(Lanier Washington) totally lied to him and cheated him," she said. "Some of the things probably are legit, but a lot of it — I mean, it's how Lanier Washington was making money.

"I'm sure he wasn't the only one out there."

The Washington hair at the Museum of the American Revolution did not come from a grifter relative, though Newell concedes that without DNA testing, there's no way to be certain of its legitimacy. The museum's sample belonged to a Dr. John Scott, whose backstory is unknown, and was later bought by the Rev. W. Herbert Burk, a Norristown preacher whose Washington artifacts formed the foundation of the museum's collection. It also once belonged to the Peale's Museum, the Philly institution founded by artist Charles Willson Peale in 1786. The museum closed shortly after his death in 1827, and his descendants sold most of the collection to a well-known arbiter of authenticity, P.T. Barnum.

As for the hair itself, it appears almost blond up close, a sharp departure from the white mane in Washington's most well-known portraits. Though the first president sprinkled his naturally reddish-brown hair with a (likely expensive) powder, he did not wear wigs, favoring instead the military style of pulling his hair back tightly into a braid or ponytail. Washington then teased out his side curls to mimic the appearance of a wig, without ever committing to the high-society trend.

Still, between the powder, pomade and silk bag he often donned to keep powder off his dark suits, it's clear the nation's first president cared just as much about his hair as his many adoring fans.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice

Kristin Hunt/for PhillyVoice