March 14, 2017

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

An aerial view of Logan Circle and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Logan Square's history, as rich and diverse as any of founder William Penn's original squares, includes public executions, burial grounds and world-famous museums.

Each spring, the blossoming of the Paulownia trees in Logan Square transforms the landscaped traffic circle into one of the most scenic sites in Philadelphia.

By the summertime, students at Hallahan Catholic Girls High School will slip into the Swann Memorial Fountain to mark the end of the school year. Others looking to cool off on a muggy day will do likewise.

Yet, Logan Square was not always so sunny. Its history, as rich and diverse as any of founder William Penn's original squares, includes public executions, burial grounds and revamped neighborhoods.

Originally known as Northwest Square, its history also includes visits by a pair of popes and one of the most famous American presidents.

Alongside the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, it has played host to numerous large-scale events, with another — the NFL Draft — coming in April.

Here's a look back at some notable moments since Penn first unveiled plans for the square in 1682.

William Penn envisioned Philadelphia's settlers buying up plots along the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers, with the city's edges slowly pushing inward. Instead, the city initially developed along the Delaware and gradually moved westward.

Logan Square was slow to develop in the years after the city's founding as a result. The areas around the square remained untouched hardwood forest for much of the 18th century.

By the 1800s, the western side of Philadelphia included country estates and farms. Logan Square itself was a potter's field used as a pasture, graveyard and execution ground.

Many of Penn's squares initially served as a public burial space for foreigners, convicted criminals, indigent poor and African Americans. Logan Square was no exception.

Over the years, coffins and human remains have been uncovered in Logan Square. In 1890, a plumber uncovered an intact coffin and human remains on the north edge of the square. Just seven years ago, archaeologists found about 60 intact graves at Sister Cities Park, located on the square's east end.

Logan Square did not begin to take the form of a park until sometime after 1825, when the renamed square was improved with walkways and plantings. Decades later, iron railings also were installed.

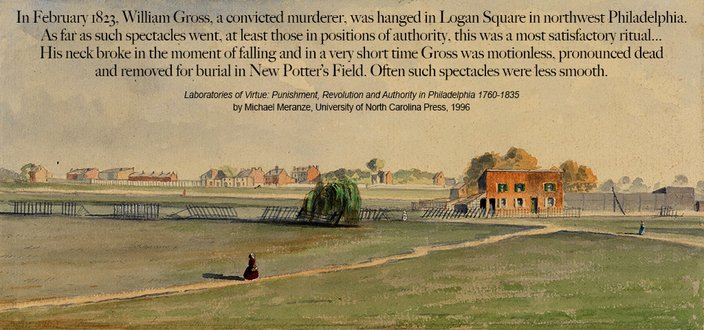

This watercolor by David Johnson Kennedy shows Logan Square (Potters Field), from Vine Street looking toward Market Street, in 1836.

Huge crowds reportedly came to Logan Square on Feb. 7, 1823 to witness the execution of William Gross, a one-time orphan convicted of murdering his mistress.

More than one hundred people previously had been executed in Philadelphia. But Gross' hanging marked the city's last public execution.

Criminal punishment was shifting away from physical coercion and public humiliation, long-believed to serve as a criminal deterrent, toward the silent confinement and soul redemption practices later propagated at Eastern State Penitentiary.

A repentant Gross, 27, who had stabbed Keziah Stow to death following an argument about her social life, delivered a scaffold warning against gambling and bad company, according to Michael Meranze, who documented Gross's execution in his 1996 book, "Laboratories of Virtue: Punishment, Revolution and Authority in Philadelphia."

Gross also had authored a pamphlet detailing the ways his addiction to gambling, dancing and other vices had led to Stow's slaying and his capital punishment. Distributed among the crowd, it included a note to his mother, a description of his prison experience and a copy of the hymn sung at his hanging.

Gross reportedly died quickly, his neck snapping as he fell. That was unlike some hangings, in which the victim died by strangulation or the drop was bungled altogether.

Sometimes, public executions drew sympathy for the victim or discontent if the public doubted the verdict or disagreed with the punishment.

"There was no guarantee that the lesson of the scaffold would be learned as it was taught," Meranze wrote. "The state, through a ritual designed to reaffirm the bonds of a public community, risked turning the criminal into a martyr or hero."

A few months after Gross's execution, the cornerstone of Eastern State Penitentiary was set in place, ushering in a new model for criminal punishment.

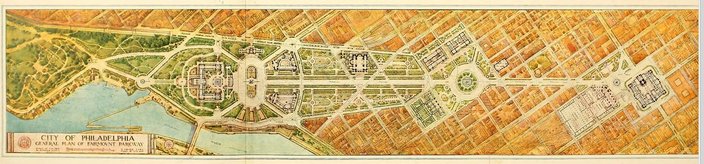

This map shows a plan of The Fairmount Parkway, better known today as Benjamin Franklin Parkway, including the Logan Square traffic circle at right. From “The Fairmount Parkway: A Pictorial Record,” 1919, Fairmount Park Art Association.

Logan Square was known as Northwest Square until 1825, when the city renamed four of its public squares to commemorate its history.

James Logan, the square's namesake, served myriad roles within colonial Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia mayor and chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. But he first came to Philadelphia to serve as William Penn's colonial secretary.

The square was named for statesman James Logan.

When their boat, the "Canterbury," was attacked by pirates, Logan helped defend it while the pacifist Penn retired below. Afterward, Penn reportedly lectured Logan, protesting his actions.

As a public official, Logan advocated for proprietary rights. He also gained considerable wealth through his business ventures, which included fur trading and land investment, and built an estate, known as Stenton, in the Germantown area.

An avid reader, Logan had a private library comprising nearly 3,000 books that are now housed by the Library Company of Philadelphia. Coincidentally, the Parkway Central Library — the main hub of the city's public library — borders the north side of Logan Square.

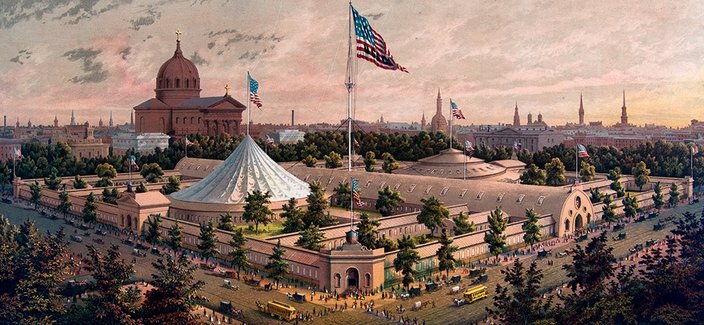

Artist James Queen captured the scene at Logan Square during the Great Central Fair in June 1864. President Abraham Lincoln attended the three-week-long fundraiser to benefit sick and wounded Union soldiers.

Logan Square has hosted some of the most of the most massive, if not prominent, events in Philadelphia's storied history.

Most have come in the decades since the square was absorbed by the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. But in 1864, the square hosted The Great Central Fair, a three-week-long fundraiser benefiting sick and wounded Union soldiers.

As the Civil War stretched into its fourth year, cities across the Union began hosting sanitary fairs designed to benefit the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a precursor to the American Red Cross.

Philadelphia's fair, among the biggest, was attended by President Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln visited during the middle of the event, accompanied by his wife, Mary, and their son, Todd. He signed 48 copies of his Emancipation Proclamation, which sold for $10 apiece.

The fair raised more than $1 million, outdone only by New York. It averaged more than 29,000 people each day, with Lincoln's appearance particularly crowded.

For $1 admission, fairgoers could view more than 100 booths, including fine arts galleries, a "curiosities and Relics" exhibit and "Arms and Trophies." They also could smoke Turkish cigarettes or sip beers.

The fairgrounds included massive temporary structures, all built within 40 days by volunteer laborers. Union Avenue, the central exhibit space, sat in the middle of the 200,000 square-foot complex, which included two large rotundas, gothic arches and connecting corridors.

The fairgrounds sat in the shadow of the Basilica Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul, which opened on the east side of the square that same year.

The 'Schuylkill Girl' is one of three figures in Logan Square's Swann Memorial Fountain that represent the major waterways in the Philadelphia region.

The development of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, designed to resemble the Champs Elysees in Paris, in the early 20th century forever changed the working-class neighborhood surrounding Logan Square.

By the parkway's completion, some 1,300 residential, commercial and industrial buildings had been razed. And Logan Square was no longer a square.

The Parkway was designed to curve around Logan Square, effectively creating Logan Circle. Like the Parkway, the circle has Parisian influences. Architect Jacques Greber modeled the circle after the Place de la Concorde.

The circle's centerpiece, the Swann Memorial Fountain by sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder, pays tribute to the founder of the Philadelphia Fountain Society. Its three bronze figures represent Wissahickon Creek and the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers. Surrounding the fountain are 12 Paulownia trees that blossom every spring.

The square's transformation added Logan Circle to the city's lexicon.

To some extent, the terms Logan Square and Logan Circle are used interchangeably, but Logan Square also includes two smaller parks sliced apart by the circle. Aviatar Park sits to the west of the circle, across from the Franklin Institute. Sister Cities Park is east of the circle, in front of the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul.

Logan Square also can refer to the neighborhood surrounding the public square. The Logan Square Civic Association defines the neighborhood as the area north of Market Street, west of Broad Street and south of Spring Garden Street. The Schuylkill River marks its western border.

Thanks mostly to its connection to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Logan Square occasionally plays a part in large-scale events.

In 2005, the crowds for the Live 8 concert stretched into the square. Earlier this year, it served as the starting location for the Women's March on Philadelphia, which drew thousands of protesters following the inauguration of President Donald Trump.

But its most notable modern events, perhaps fittingly, include a pair of Catholic Masses.

Pope John Paul II celebrated Mass on an altar constructed atop Logan Circle fountain as part of his much-heralded tour of the United States in 1979. The event is said to have brought between 1.2 million and 2 million pilgrims to Center City.

When Pope Francis held public Mass on the Parkway in 2015, the crowds stretched through Logan Square. And as Francis circled the crowds on his popemobile, he made an unscheduled stop to bless the Knotted Grotto alongside the Basilica.

The events marked a notable difference from when the cathedral was erected in the 1860s, when anti-Catholic furor spurred church officials to avoid low-level windows that would be susceptible to vandalism.

This photo of the Academy of Natural Sciences at 19th and Race streets in Logan Square was taken circa 1892. The academy was joined on the square by the Franklin Institute in 1934. Today, the Barnes Museum, the Rodin Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art all sit along the Parkway.

Today, Logan Square and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway boast world-class museums and educational institutions.

That designation stretches back to 1876, when the Academy of Natural Sciences moved into a location bordering the south side of Logan Square. The museum still boasts one of the world's largest collections of bird specimens.

That same year, The Academy of Fine Arts opened its current building just a few blocks east of Logan Square.

The Central Library building, also designed with Parisian influences, opened in 1927. The Franklin Institute — the most famous museum sitting on the square itself — followed in 1934, moving from a smaller location on South Seventh Street.

The Basilica, the head church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, and the former Family Court building — a twin to the library — also border the square. And other prominent neighbors are within walking distance of the square.

The city's Mormon temple, which opened in 2016 and pays homage to colonial Philadelphia, sits just northeast of the square.

The Barnes Museum, the Rodin Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art all sit along the Parkway, which forever revamped the look of Logan Square.

Source/Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Source/Historical Society of Pennsylvania Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org Source/Wikimedia

Source/Wikimedia Source/Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Source/Historical Society of Pennsylvania Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice Source/PhillyHistory.org

Source/PhillyHistory.org