September 07, 2016

Handout Art/Quaker City Mercantile

Handout Art/Quaker City Mercantile

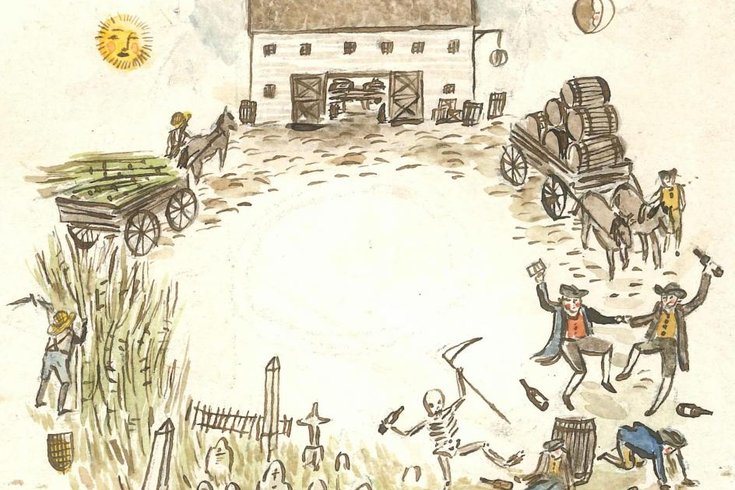

Art from Steve Grasse's 'Colonial Spirits" book of colonial drink recipes.

Quaker City Mercantile principal, Philly native and all-around booze connoisseur Steven Grasse has a new book out this fall, and boy is it a doozy.

In "Colonial Spirits: A Toast to Our Drunken History," out Sept. 15, Grasse explores the history of drinking in Colonial America, commissions some quirky folk illustrations and excavates cocktail and beer recipes that have been buried for hundreds of years. If not a great coffee table piece, it's most definitely a pretty rad gift. (Bookmark it for the upcoming holidays, people.)

Here, Grasse talks scrappy colonials who would probably qualify as alcoholics today, the original craft beer movement and what Ben Franklin was drinking while inventing all those important things.

Why did you write this book?

Two very obvious reasons.I am in the spirit business — I create spirits brands and I own a distillery. And the second thing, is I’m a history buff. Particularly the colonial and federal periods with emphasis on Philadelphia. So my two worlds have come together in one smashing book.

‘We got drunk and invented America' is how you're pitching the story of the book. How literal are you being when you say that?

Well, what’s interesting is, contrary to popular beliefs, people drank a lot in those days, and everyone drank — from grandpas down to kids because the water wasn’t safe. But also, it’s just what you did. For instance, the taverns were for widespread — they were where political dissent reached a fever pitch, and all those sorts of things. And I think the real interesting thing about the book — and a scenario not covered before — is you get into the whole folk recipes and things, because what happened in America is when they came here they made spirits out of whatever they could get their hands on. For instance, that’s why American beers tend to be corn-based or adjuncts. Because you couldn’t get ahold of the barley or hops.

The book goes as far back as 1600, but I can’t imagine the colonies — barely surviving in many cases — were even making alcohol.

It was a simple ingredient of life! If you think of [the word 'whiskey'] it literally means ‘water of life.’ So, spirits were a very essential part of peoples' lives back then. It started with the idea that the water wasn’t safe. But spirits were also seen as medicines. So a lot of bitters we use in cocktail ingredients today actually started as medicine.

There's a recipe in the book for cock ale. It’s chicken stock in beer. And it was seen as an aphrodisiac. Like 18th-century Viagra.

My understanding is that Quakers actually drank quite a bit?

They drank quite a bit in the sense of ciders and ale, but that wasn’t really considered serious drinking. Again, it’s what you drank. And you drank it for breakfast. Because you couldn't drink water.”

How were they mixing up cocktails? How'd they feel about shake v. stir?

Well, they weren’t really making cocktails — cocktails as we know them didn’t exist. A lot of times the alcohol was so strong they would mix in herbs and fruit juices just to dull the taste, but really what people drank back then was punch. And it would come out in a huge bowl with a ladle, and just be passed around until it was gone. But that stuff was lethal. We have quite a few recipes in the book — particularly the Fish House Punch, which was based in Philadelphia. And I mean, yeah — so 17th- and 18th-century cocktails were usually in the form of punch.

How did you research what the Ben Franklins and Thomas Jeffersons were drinking?

Well, what we did, our process was to go through and research tons of old recipes. And there are various ways you can do that. By finding old tomes. Then also as simple as going on the internet. But finding these old recipes was tricky because we include a lot of these old recipes in the book.You then have to translate them for modern day. 'How can you translate that to modern day ingredients?' Our process was to research the old ingredients and then work with our team of mixologists and chefs to then translate these ingredients into something you could do at home. And our publisher was insistent we test them all so they wouldn’t kill you. [Laughs]

So people can rest assured they won’t die from these old recipes.

They won’t die unless they make it very wrong, yes.

How does our drinking culture compare? Were they drinking more?

Oh totally. Much more. It was an all-day affair. You’d get up in the morning and drink. All day into the evening. It was a big part of your calorie intake back then. The way we drink now, it’s also the way we process food. So, a lot of what we drink is kind of crap. I do think our beer culture has changed significantly. Because I would think the proliferation of craft beer rivals — if not exceeds — what was going on back in that time. Everyone made their own beers but there are far more styles to choose now than back then, but that’s only recent. We’ve come full circle. It was only 20 years ago there were only 10 major breweries in America. Now there are almost 5,000.

In some ways, we’re going full circle. The same is true of craft distilling. We own a craft distillery in New Hampshire, and what’s going on is it’s all becoming local again. Back in the day, people would make their own gin out of their own garden ingredients. And now they’re doing that again. So it’s really come full circle, but only in the last 10 or 15 years. It’s exciting.

Our business is, we make spirits but also consult with all the major spirits and beer companies around the world. One of the things I do is work with Guinness in Ireland, and they were founded in 1759. We have recently come out — we went through historical archives and came out with Guinness styles that hadn’t been out for 250 years. An Irish porter and West Indies porter we recently launched out of their historical archives. What we do with this book is actually how I make money for a living. I go through all these big companies and find out how they used to make stuff and remake it.

So, George Washington. Did he really drink applejack, or is that just a branding thing?

I’m sure George Washington drank applejack. Lairds. Lairds was a distilling [company] with License No. 1. They’re still in business. That applejack that Lards sells really has nothing to do with the historical recipe. Apple-jacking, the way you made applejack back in the day, wasn’t distilled. You took fermented hard cider and put it out in very cold temperatures, and then you skim off the concentrated alcohol and do it again and again until it becomes high-proof. Applejack today is really apple whiskey. So you take a brandy and barrel age it for however long. The Lairds applejack, made in New Jersey, isn’t true applejack. It’s made with neutral grain spirit.

It’s kind of a fraud.

If all these Founding Father folks were drunk at the time, maybe we should put less weight into the documents they produced.

Washington did — he had the biggest distillery in America at one point, actually. He made rye whiskey. He was quite profitable at it, too. And they’ve recently reconstructed his distillery and it’s doing very well. They do it quite authentically.

What was Ben Franklin drinking?

Steve Grasse, author of 'Colonial Spirits' and founder of brand consulting firm Quaker City Mercantile.

He really liked everything. He drank Madeira. Which is aromatized wine, like a vermouth or sherry, but it comes from the island of Madeira. But he also drank cider. And rum. Rum was what most of us drank in Philadelphia. It wasn’t until after the — during the revolution when the British cut off our sugar supply, that we turned to making whiskey. And there’s a whole story past with whiskey and we make – it was all rye whiskey for a time, and then the whiskey rebellion with Alexander Hamilton caused all the Scottish and Irish immigrants to say ‘Screw this. Let's move to Kentucky, Bourbon County, and make corn.’ And that’s how we got bourbon.

And there's a great story in the book about how rum was really part of [Triangular Trade], with the slave trade, and Brown University was really the big slave trader... And Yale; that was also a big slave trader. It was all about the rum sales. So, all these college kids having these student protests need to understand they should be up in arms. Brown should change its name because it’s founded on slave money by rum. Stuff like that.

What can brewers today take from looking at the past?

I think back then they were much more experimental. Because they needed to make things out of what was available to them. So, for instance, spruce ale. They used spruce tips because they couldn’t get enough hops. So I think that, again, it’s this idea of going full circle. I think we’ve learned already. We’re already doing that, with the craft movement coming back. Stay the course and keep doing that.

Also, there’s a lot of great recipes in there. Bartenders should buy this book to make new syrups to use in their mixology.

Tell me about the cutesy art.

OK, so the Reverend Michael Alan is someone we worked with for years, he did all the Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction spirits brands — the labels. He’s also a chef. So not only did he do the artwork, but he was the guy who was given the impossible recipes and found a way to translate them with modern ingredients. Michael’s role in the book was beyond just doing the art. He did it in a very Pennsylvania folk style but also a federal era — it’s very authentic to the era, but we had fun with it as well.

Have a favorite recipe from the book?

I like cock ale. And it works, too. There’s also the spruce ale. In November we’re coming out with spruce ale as well. Narragansett is one of our brands, and we’re releasing a limited-edition spruce ale in November. To go along with the book. And we’re also releasing a cherry bounce recipe, Martha Washington's. Whiskey with cherry. And it’s delicious. We’ve made that in our distillery in New Hampshire and that will be for sale in limited batches.

Anything I missed?

We tried to make history fun. And we put it into a format that you can digest it even if reading tomes of history isn’t your thing.

'1775 Punch,' from Steve Grasse's spirits recipe book, 'Colonial Spirits.'

2 limes thinly sliced

4 1/4 cups gold rum

2 1/2 cups pineapple juice

1 1/4 cups fresh lime juice

6 cups spiced black tea

• Arrange the lime slices on the bottom of a Bundt pan. Fill the pan with water to cover the slices and freeze until solid

• In a 1-gallon container, combine the rum, pineapple juice, lime juice and tea. Cover and chill until cold

• Transfer the chilled mixture to a punch bowl and add the frozen lime ice ring

• Serve the rum punch in glasses full of ice

Handout Art/Quaker City Mercantile

Handout Art/Quaker City Mercantile