December 14, 2015

Provided by Joel Feldman/For PhillyVoice

Provided by Joel Feldman/For PhillyVoice

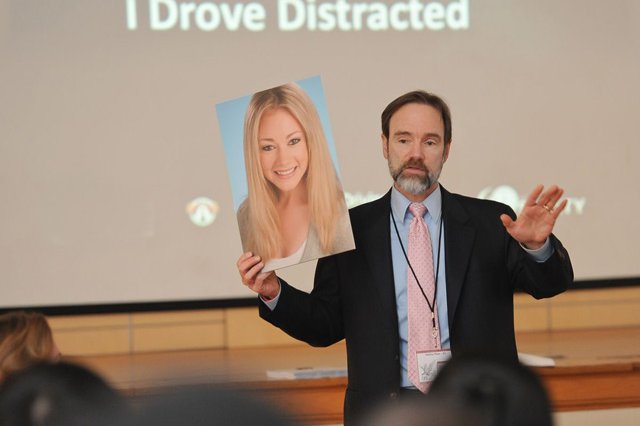

Joel Feldman holds a poster with a photo of his daugher Casey, who was killed in Ocean City, NJ after being struck in a crosswalk by a distracted driver.

“When you lose somebody who should bury you, you question everything and there’s no answer that’s ever satisfying.”

Those are the words of Joel Feldman, a Philadelphia attorney who – in 2009 – faced the horrendous burden faced by parents who bury their children.

Casey, his 21-year-old aspiring-journalist daughter, died after being struck by a distracted driver while she was heading to her summer waitressing job in Ocean City, New Jersey.

The driver would plead guilty to careless driving and get a $200 fine; he’d been fiddling around with a GPS device in the vehicle. The mourning father was left to do the type of soul searching that alters the course of one’s life.

“Today, it’s culturally unacceptable to drive drunk, but it’s not that way yet with driving distracted. I’m optimistic that the younger generation can make that change.”-- Joel Feldman, EndDD.org

“People used to say that ‘you must hate the guy,’ and it would be different if he’d been on drugs or driving drunk,” said Feldman on Friday. “Instead, I had this nagging thought in the back of my mind that 'I drive distracted, I do what he did.' It felt hypocritical. It took my daughter’s death to change the way I drive.”

Feldman talked to PhillyVoice a day after taking his "End Driving Distracted" mission to The Today Show and several days before he’ll continue a speaking engagement commitment on Wednesday night at Lower Merion High School.

The years since Casey’s death have seen Feldman and wife Dianne Anderson create The Casey Feldman Memorial Foundation and EndDD.org. He’s given more than 300 presentations in an effort to tell some 60,000 youths – and their parents – that distracted driving leads to injury and/or death but is a bad habit that can be broken.

“We told a bunch of parents to come if you want to keep your kids safe, and they think we’re going to lecture the kids,” he said of an upcoming event. “But, it’s going to turn on mom and dad, who are not being good role models in this respect.

“Seventy-five percent of drivers admit to driving distracted, whether it’s cell phones, apps, playing Tetris. I’ve heard, eight times across the country, of breast feeding while driving. I heard someone say their dad brings a quart of milk, Cheerios, a bowl, a spoon and eats breakfast in the car. We laugh about that, but it’s kind of sick.”

The ultimate goal is to bring about a cultural change akin to the gradual vilification of drunk driving, potentially in the form of a national law against distracted driving.

“I drove distracted all the time before Casey was killed, and represented tons of people in these cases,” he said, hearkening back to a story about a dump-truck driver who crossed the center line and caused a collision that left a four-year-old dead because he was looking at “a hot girl in shorts” walking into a convenience store.

Still practicing law part-time with the firm Anapol Weiss, Feldman said that he’s optimistic that distracted-driving campaigns are making a difference as youths seem to grasp the message to the point of chastising their parents for unsafe vehicular behavior.

Feldman notes that most of the presentations end with parents signing “safe-driving agreements” as their distracted-driving habits came more into focus when forced to think about them in that manner.

He estimated that he’s talked to roughly 100 parents who’ve lost children and about 25 who’ve killed while driving distracted.

“What they tell me is that 'it was just for a few seconds, that it was an important call, that they didn’t think anything bad would happen,'” he said. “I haven’t been to a high school anywhere in America where there wasn’t an administrator, teacher, parent who didn’t admit they drive distracted. It’s pretty easy for them to control when it’s presented as doing something to keep their kids safe.”

Between studies – and anecdotal observations – Feldman is confident that the message is getting through to youths that they shouldn’t follow the lead of parents who drive while distracted. He noted that he’s only gotten one email critical of his approach.

Getting word out has also been easy thanks to companies like Travelers Insurance – which has sponsored his End Distracted Driving effort at several races including October’s Rock ‘n’ Roll Half Marathon in Philadelphia. He also received 2013 Magee Rehabilitation Hospital Humanitarian of the Year Award.

Education, he said, is a key component of changing behaviors when laws are slowly catching up to the dangers while it’s not feasible to expect something like a “blood test” to detect instances of distracted driving.

“Today, it’s culturally unacceptable to drive drunk, but it’s not that way yet with driving distracted. I’m optimistic that the younger generation can make that change,” he said.

“I was talking at a high school in Kansas City and a young mother came up and said her five-year-old daughter has one of those orange and yellow Fisher Price cars, but flips out every time unless she has a cell phone because she ‘wants to drive like mommy,’" he continued. "Children learn from adults. The only thing you can do is model safe driving and be the driver you want them to be.”