April 19, 2016

Hayden Mitman/PhillyVoice

Hayden Mitman/PhillyVoice

Susan Gobreski, community schools director for the Mayor's Office of Education in Philadelphia.

Susan Gobreski has her work cut out for her.

The newly appointed director of the community schools initiative for the city's Office of Education is tasked with bringing a potentially transformative citywide program to Philadelphia.

With a proposed budget of about $39.6 million over the next five years, Gobreski and her team plan to transform 25 city schools into "community schools" over the next five years – at a pace of about five to seven a year. In an interview Thursday we chatted with Gobreski about the program:

So what's a "community school"?

The initiative has been promoted as a way to transform schools into community hubs to boost student performance and revitalize neighborhoods by providing access to basic programs and services. It would involve a coordinated effort by parents, educators and community members.

Right now, the education office, in conjunction with the school district, is gathering feedback from students, parents, school administrators and staff, and service providers to learn about the communities, the potential for community partnerships, and assess the needs of schools. (On Thursday night, in fact, Gobreski attended a meeting with a group in southeast Philadelphia to gather input.)

Gobreski and her team will evaluate that feedback and ultimately select a group of schools to launch the city's program. Each community school will have its own "strategic, coordinated plan" to address the needs of its children.

A coordinator will be hired at each community school to guide how the city will provide services that "best meet the needs of the community." The coordinator, a city employee, will be in charge of working with educators and principals at community schools to enforce the plans, organize services and coordinate with community service partners.

They will also meet regularly with community members to make sure that school needs – as well as community needs – are being met.

"The whole notion of community schools is that rather than a top down, you have a bottom up framework," said Gobreski. "So schools need to make decisions about what their individual needs are."

Overall, the goal of the community schools initiative is less about directly altering academics – that's the school district's responsibility – and more about removing barriers to learning, she added.

That spurs academic achievement, she said.

What types of "individual needs" will these community schools fill?

Depending on the needs of the neighborhood, the new community schools could look very different. But some examples of the types of services that could be provided include literacy programs, food banks, health services and career training programs.

"Part of the notion of this is: this is something more than a school," Gobreski said. "It's a strengthening of the neighborhood and bringing an increased capacity of community services to the neighborhood."

Last year, Kenney and other elected officials from the city traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, to learn about community schools, see them in action and learn how to create them here.

"Children have a set of needs and, right now, we've placed the responsibility for dealing with those needs entirely on the school system. The schools are expected to produce the same results for a kid, no matter if they are poor or hungry or have an asthma problem that's untreated, or whether or not they have a tutor at home, and that's really not reality." – Susan Gobreski, community schools director for the Mayor's Office of Education

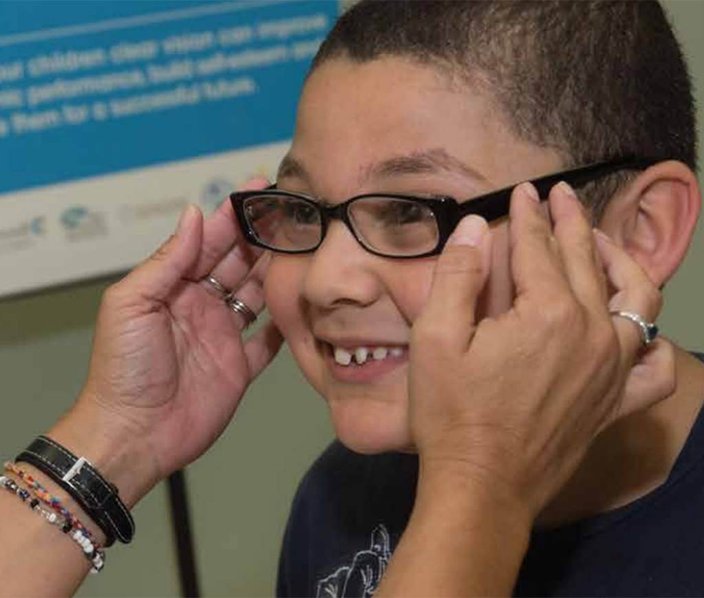

During that trip, they toured Oyler Community Learning Center, a community school that boasts optometry and dental services for children.

That transformation cost $21 million and, as pointed out recently by Anna Orso at Billy Penn, just how the community schools model has improved academics at that school remains to be seen – state test scores improved for a bit, but graduation rates there are still under 50 percent.

But Julie Doppler, coordinator of community learning centers for Cincinnati Public Schools, has said that independent evaluations suggest the effort has helped it become the highest-performing urban school system in Ohio. Data consistently show, she said, that students targeted for community learning center services show performance gains.

The OneSight Vision Center at Oyler School in Cincinnati is the first self-sustaining school-based vision center in the United States. Opened in October 2012, it served thousands of public, private and parochial students. Oyler is a community learning center.

Are there other examples nationwide of successful community schools?

The Mayor's Office of Education cites other examples.

Kentucky, once one of the worst-ranked states for education, has risen to the top 50 percent of states in education after implementing community schools plans. More than 25 years ago, that state committed funds and resources to transform every school with 20 percent or more of students living in poverty into a community school.

And in Austin, Texas, two of the lowest performing schools in the district – Reagan High School and Webb Middle School – implemented community schools plans and became two of the highest-performing schools in that city. According to its annual report, campus-based programming includes crisis intervention, individual counseling, support groups, life skills, tutoring and mentoring.

When will the community schools be selected?

No schools have been selected yet to become community schools, Gobreski said. Meanwhile, the Office of Education is taking socioeconomic factors and geography into account along with other factors as they consider their choices.

In some cases, she said, access to grocery stores, the age of school buildings, or the amount of special needs students at a school are all factors that could be considered.

"We will be taking a look at a lot of need indicators," said Gobreski. "Some places, there's really nothing going on but the school... We want to be really smart and intentional in how we are providing the resources."

How long before improvement can be expected?

"Academics are sort of the long-term target on this," Gobreski said, noting that "the full effect will take a little while. It's not instantaneous."

Instead, the plans are focused on improving conditions for students at these schools so that the school district and educators have a better path to engaging students and working to improve attendance rates, grades, and promotions/graduations.

"Children have a set of needs and, right now, we've placed the responsibility for dealing with those needs entirely on the school system," she said. "The schools are expected to produce the same results for a kid, no matter if they are poor or hungry or have an asthma problem that's untreated, or whether or not they have a tutor at home, and that's really not reality.

"So, what we want to do is say, 'Look, we can do a better job at providing supports and services to meet – the term that is used in education circles is – the needs of the whole child'."

• • •

To find out about upcoming meetings on the community schools plan in your neighborhood, visit the office of education's website here or you can join the community school initiative's mailing list, here.