July 14, 2023

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory/United States National Archives and Records Administration

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory/United States National Archives and Records Administration

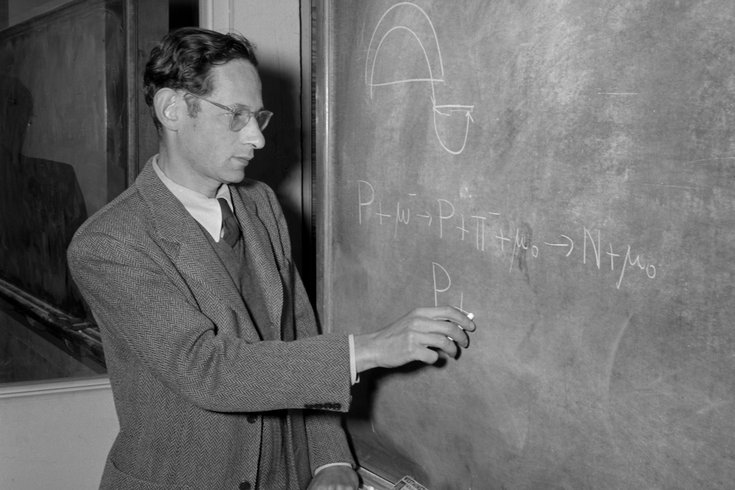

Robert Serber, shown above in 1948, followed his mentor J. Robert Oppenheimer from Berkeley to the secret Los Alamos National Laboratory, where the atomic bomb was developed.

Mere weeks after atomic bombs leveled the Japanese cities of Nagaski and Hiroshima in 1945, a physicist from Philadelphia traveled abroad to report on the impact. He met locals with discolorations, almost like sunburn, streaked across their faces and passed trees with sickly shades of yellow and brown. Nothing two miles from the Nagaski explosion had withstood the blast.

"No one that has not actually seen the completeness and utterness of the destruction...can have any idea what a terrible thing atomic warfare is," he wrote. The damage was "so great that it will never be possible to know accurately how many people were killed."

Robert Serber was no ordinary bystander to these tragedies. He was one of the American scientists who built the bombs that created them.

Serber was one of the many members of the Manhattan Project, a massive World War II research and development project aimed at creating the world's first nuclear weapons. As the longtime protege and friend of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called father of the atomic bomb, Serber was called to the Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1943, spending two years at the secret New Mexico site working out the theoretical physics that would make the bomb possible. He will be fictionalized, for at least the third time, by actor Michael Angarano in the upcoming blockbuster "Oppenheimer," out Friday, July 21.

Serber was born into a family of Russian and Polish Jewish immigrants in West Philly in 1909. In his memoir "Peace & War," he recalls living in a house on 41st Street near Girard Avenue, right by Fairmount Park. "I spent a lot of time wandering around the park — along the banks of the Schuylkill River and in Horticultural Hall and Memorial Hall, both of which had been built at the time of the Centennial celebration in Philadelphia in 1876," he wrote. (Horticultural Hall was destroyed by a hurricane in 1954.) He later graduated from Central High School and Lehigh University, working summers at Philadelphia oil refineries and gasworks — the latter of which apparently paid him in gold.

After earning a PhD at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Serber planned to accept a fellowship at Princeton. That was until he met Oppenheimer at a University of Michigan physics summer school. "His mind was so quick and his speech so fluent that he dominated nearly every gathering," Serber wrote. "I soon became fascinated by him." On the spot, Serber decided to switch his fellowship from Princeton to the University of California, Berkeley, where Oppenheimer was a faculty member. Serber and his wife Charlotte packed up their lives and drove cross-country in a secondhand Nash-Healey roadster, which broke down 13 miles outside of Berkeley.

Oppenheimer's friendship with Serber truly began a week or two later, when the pair went to the movies to see the 1937 thriller "Night Must Fall." The Serbers soon became regular guests at Oppenheimer's rather inhospitable Perro Caliente ranch in New Mexico, where amenities included one sofa and running water. Under Oppenheimer's guidance, Serber quickly became involved in nuclear physics research at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory. According to Oppenheimer biographers Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, he believed Serber was "one of the few really first rate theoretical men" he had worked with.

Serber had moved on to a position at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign when America joined World War II. But after a call from Oppenheimer, he quietly left the campus to travel back to Berkeley and work on the atom bomb project his mentor was now running. He and Charlotte lived in a room over Oppenheimer's garage.

After spending much of 1942 working out the calculations for the bomb, Serber and Oppenheimer's entire team moved to a secret laboratory in Los Alamos, near the Perro Caliente ranch. Serber was tasked with delivering a series of lectures on the basic principles of the bomb to new recruits, the content of which was later collected into the Los Alamos Primer, a document that would not be declassified until 1965. Charlotte, meanwhile, worked as the site librarian, making her the only female group leader on the Manhattan Project — a role she nearly lost over her leftist politics. Unbeknownst to her or Robert, the FBI wiretapped the couple during their time at Los Alamos and they were nearly fired due to suspected Communist beliefs and association with "radicals."

Oppenheimer would also not permit Charlotte to attend the Trinity test, the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, on July 16, 1945, citing the lack of "sanitary facilities" at the site. But Serber was present, and recalled the explosion in great detail in his memoir:

"We left for the viewing site that night and got there about three in the morning. It was cold, damp and there were thunderstorms around which delayed the test. At about 5:30 it cleared up a bit and a warning rocket went off in the distance. We all lay down facing the test site. We'd each been issued a pair of welder's glass to shield our eyes, and were supposed to hold them up while awaiting the explosion. Of course, just at the moment my arm got tired and I lowered the glass for a second, the bomb went off. I was completely blinded by the flash, and when I finally began to regain my vision the first thing I saw was a violet column that must have been very bright and was thousands of feet high. In about half a minute my vision cleared and I saw a white cloud rising, to what must have been twenty, thirty, forty thousand feet high. I could feel the heat on my face a full twenty miles away. The fireball was about as bright as the sun on a clear summer afternoon."

Serber also named the project's various prototypes, drawing inspiration from popular stories of the time. The plutonium assembly gun was the "Thin Man," named after the Dashiell Hammett novel and movie, which served as the basis for the eventual "Little Boy" that was dropped over Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. The "Fat Man," which would detonate in Nagasaki three days later, referenced a character in Hammett's "The Maltese Falcon." Serber was supposed to photograph the explosion of the "Fat Man" aboard a U.S. military plane but was kicked off at the last minute due to a shortage of parachutes.

Serber would travel to the two cities that fall, where he documented the ruins and witnessed the "completeness and utterness of the destruction." After he returned, he went back to work at Berkeley, where he developed new atom smashers and patented a pinpoint X-ray device. He faced further scrutiny from the U.S. government as McCarthyism spread, passing a security hearing in 1948 but losing security clearance to attend a conference in Japan in 1952. Serber returned to the East Coast in the 1950s for a professorship at Columbia, where he worked until his retirement in 1978. Upon his death in 1997, he was dubbed "the intellectual midwife at the birth of the atomic bomb."

But Serber indicated some reservations over nuclear warfare later in his life, joining over 15,000 physicists in signing a 1983 letter to the United Nations calling for a de-escalation of the nuclear arms race. But he generally celebrated his work with Oppenheimer, and praised his mentor in life and after his death in 1967, the same year as Charlotte. (Serber would take up with Oppenheimer's widow Kitty, embarking on planned trip around the world with her aboard a sailboat they dubbed the Moonraker. The trip ended abruptly in Panama, where Kitty died of an embolism.)

"Oppie had told me that the medical corps was prepared for half a million casualties, and I had no reason to doubt him," he wrote in a 1995 article for The Sciences. "My thoughts about the wisdom of using the atomic bomb to bring a quick end to the war have not changed a bit since then."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.