June 30, 2016

NJ DEP//Provided photo

NJ DEP//Provided photo

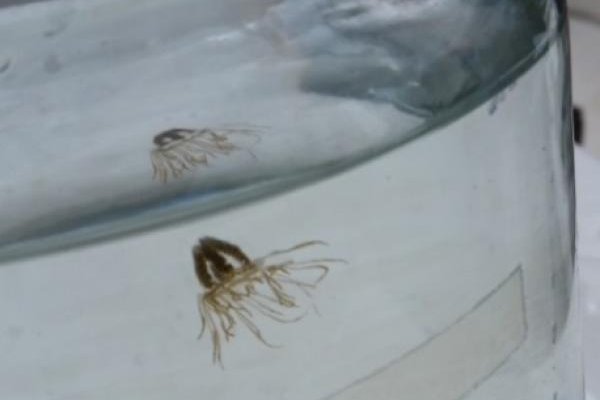

Tiny and translucent clinging jellyfish with a potent poisonous venom have made an appearance on the New Jersey coast for the first time ever. Their sting can be excruciating. The DEP is studying them, hoping to map their occurrence and track their DNA to determine where they originated.

A bigger boat is not gonna help.

A clinging — and stinging — organism has blossomed off the New Jersey coast this summer. And it's tiny.

Even worse, the poisonous venom in the tentacles of the clinging jellyfish showing up in Jersey waters is more potent — and more excruciatingly painful — than the venom found in other populations of the same species in neighboring states.

Sting operation: Jellyfish targeted before they can multiply

Just how bad is the sting?

A man swimming in the Shrewsbury River at Monmouth Beach, about nine miles north of Asbury Park, was hospitalized for two days in June. The venom can cause muscle weakness and other medical problems, including most seriously kidney failure.

A single tentacle sting feels like a jab with a hypodermic needle. But the tiny critter — less than an inch in diameter — has up to 90 sticky tentacles. More contact with more tentacles means more venom — and more pain.

Water sports events on the Shrewsbury, Navesink and Manasquan rivers were canceled this summer as a result of the jellyfish incursion.

That’s a pretty scary effect for a hard-to-see clear blob about the size of a dime or nickel.

They rest in shallow waters during daylight, clinging to eel grass and bay lettuce. At night they swim free, dropping down through the water feeding on tiny zooplankton. They sting their prey in order to capture it.

In reaction to the surprise invasion, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and Montclair State University have just launched a 30-day mapping study.

The study areas are on the bays and rivers of Ocean and Monmouth counties, including the northern end of Barnegat Bay, where they have not yet been detected. Clinging jellyfish do not show up in the ocean surf, which is too rough.

A plan of action is possible once the study concludes, but how that might work besides monitoring and issuing warnings is difficult to know.

“These jellyfish have been found in waters of Massachusetts and the eastern tip of Long Island, but have never been reported in noticeable numbers in New Jersey until this year,” said Gary Buchanan of the DEP. “We do not know if these recent reports of clinging jellyfish are isolated or if they are becoming established in areas of the state.”

So for now, the scary part is no one is sure why clinging jellyfish have moved into Jersey waters, according to Matt Landau, a professor at the Richard Stockton University, who has literally written the book on venomous sea critters.

“No one is clear. It could be acidity, overfishing of some fish that ate them, water temperature, too many nutrients in the water producing more algae,” said Landau, a Stockton professor for 30 years. “No one has a great answer. It’s very complicated.”

More frightening, Landau and his colleagues aren’t sure why the venom in the New Jersey population is more potent and painful than the same species in neighboring states.

But a genetic analysis planned as part of the DEP study might address that question.

Atlantic populations of clinging jellyfish range from Maine to the Carolinas, but they had until this summer bypassed New Jersey.

Landau said a strain of clinging jellyfish in Japan – they are a native Pacific species, but first showed up on the Atlantic Coast beginning in the 1890s – have always been more venomous than strains elsewhere. It’s possible that the Jersey coast iteration may have recently come from the Japanese strain, not from states north or south of New Jersey, explained Landau.

But it is also possible the little blobs in Jersey have simply evolved to deliver a more potent sting, added Landau. That's a worrisome possibility.

“Analysis of these organisms may permit us to assess their geographic origins as well as the genetic diversity and stability of these populations,” said Montclair professor John Gaynor, and “may also permit us to monitor other waterways and determine if they are present elsewhere.”

Landau has never been stung by a clinging jellyfish — Gonionemus vertens is not a true jellyfish, but it is related to the better-known Portuguese man-o'war — but he’s been tagged five or 10 times each year by a near-relative.

It isn’t pleasant and there’s not much to be done about the sting, he said.

“Some people are more sensitive than others,” said Landau. Avoidance, wetsuits and waders are the only real ways to keep from being stung.

Applying white vinegar to wash away remaining tentacles is advised, but scientists don't have an anti-venom. Doctors can, though, treat pain symptoms.

Any who sees a clinging jellyfish in a Jersey waterway is asked to report it to the state by calling 877-WARN-NJDEP.

DEP is also asking observers to take a photo from a distance.