August 04, 2023

Provided image/Yepoka Yeebo

Provided image/Yepoka Yeebo

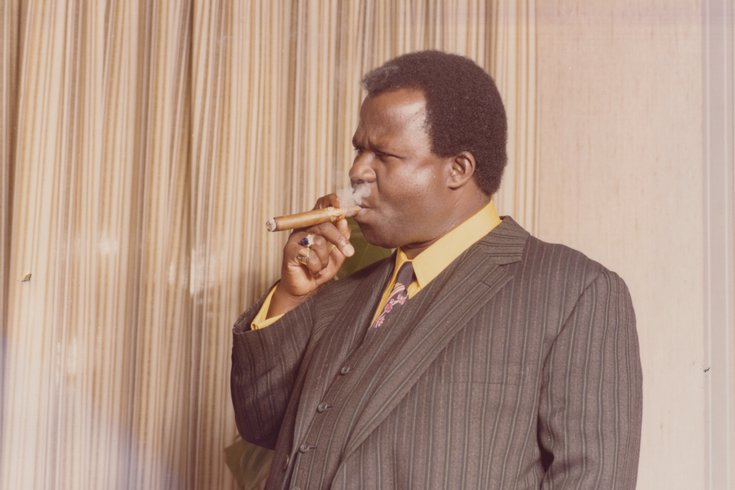

John Ackah Blay-Miezah, pictured above, solicited investors in Philadelphia in the 1970s and 1980s for a fund to develop Ghana. It was a con to enrich himself.

Over the years, there have been many stories about a man named John Ackah Blay-Miezah. That he had traveled from his native Ghana to Philadelphia for an education and he was a proud Penn grad with a medical degree. That he was related to prominent Ghanaians, including Robert Samuel Blay, a justice on the West African nation's supreme court, and Kwame Nkrumah, the country's first president. But most importantly, that he had sole access to a multi-million, possibly multi-billion, dollar fund created by Nkrumah, and he was willing to cut anyone in for the right price.

In reality, none of this was true. Blay-Miezah did not have a secret fund or family connections, and he had never even enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania. But hundreds of people in this region and all around the world believed him, enough to pour millions of their own money into Blay-Miezah's coffers. They never saw a cent of it again, but Blay-Miezah died a very rich man.

Blay-Miezah's con, which prosecutors would call the "biggest scam in the history of Philadelphia," is detailed in the new book "Anansi's Gold: The Man Who Looted the West, Outfoxed Washington and Swindled the World" by Yepoka Yeebo. The nonfiction narrative chronicles the con artist's lies and daring escapes from justice, and his many misdeeds in Philly before he left the city to escape a warrant for his arrest in 1974.

Blay-Miezah's checkered past in Philadelphia began in 1959, shortly after he sailed from the port of Takoradi in Ghana to Brooklyn. He had told his family and his new friends in America that he was pursuing a college degree at Penn, joining the wave of African immigrants seeking higher education in the City of Brotherly Love. As Yeebo writes, Lincoln University had more African students enrolled in the 1950s than any other college in the United States. Many of them were wealthy, and some even came from royal families. Others did not, but still claimed to be, leading to a proliferation of "African princes" in West Philadelphia.

"I think for a lot of people it was easier to present as like an exotic version of yourself, as an African prince, than it was as, like, a Black person in general. I think people wore it as a sort of protection in a way. (They) would reach for lots of ways to make the best of a situation and that was one," said Yeebo, a British-Ghanaian freelance journalist. "Anansi's Gold" is her first book.

But Blay-Miezah was not a royal, or even a student. While his roommates went off to class, he worked at the Union League of Philadelphia, the private club for the city's wealthiest and most influential residents. There, Yeebo writes, "he studied what money and power looked like," laying the groundwork for his decades-long scheme.

After several years back home in Ghana, Blay-Miezah returned to Philadelphia in 1972, presenting himself as a doctor with diplomatic ties. He proceeded to run up a $2,700 bill at the Bellevue, and was arrested after the hotel discovered the Ghanaian embassy would not, in fact, be covering the expense. Blay-Miezah claimed it was all a big misunderstanding, but that couldn't save him from a nearly a year-long sentence at Graterford State Prison. It would have been longer were it not for the prison chaplain, Rev. James Edward Woodruff, who was one of the first Americans to buy into Blay-Miezah's tall tales.

The basic story, which would change many times over the decades, was that Blay-Miezah had been a close ally of Ghana's President Nkrumah, who became that county's first leader after the new nation had declared independence from Great Britain. He would be deposed in a coup in 1966, and he eventually died in exile in 1972. But before he passed, as the legend went, the president had entrusted his good friend Blay-Miezah with the deed to a secret fortune: millions in gold that Nkrumah had smuggled out of the country to a Swiss bank. It was the key to Ghana's future.

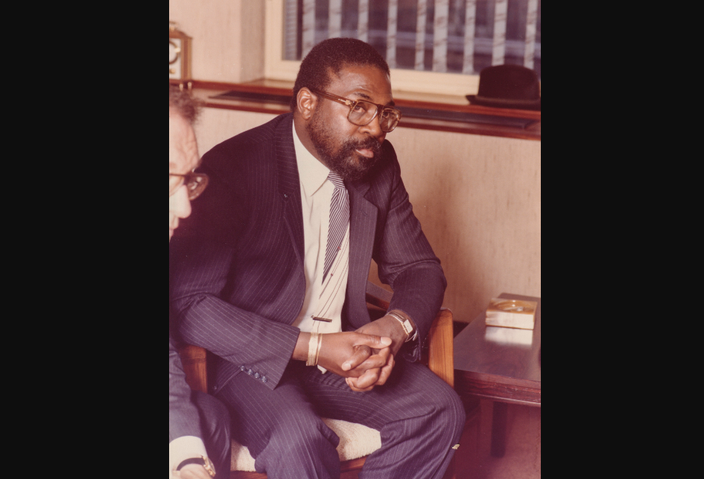

Blay-Miezah was not a good friend of Nkrumah. By some accounts, the late president had never met the man. By others, his security team had Blay-Miezah jailed. Either way, he was far too young to have been a key figure in the Nkrumah administration, but an American wouldn't necessarily know that — and just to be safe, Blay-Miezah aged himself up. The Philly reverend who heard this story, hoping to support a budding Black leader who would bring prosperity to Ghana, was able to secure his early release with the help of his friend Robert Ellis, the well-connected owner of a construction company. Ellis would become the head of the scam in Philadelphia, and would eventually go down for Blay-Miezah's crimes.

Robert Ellis, pictured above, ran the Philly operations out of offices in Bala Cynwyd. He was sentenced to prison in 1987.

But that was still years away. First, Blay-Miezah would establish an office for the Bureau of African Affairs and Industrial Development, an import-export company designed to resemble an actual government agency. From their headquarters in Bala Cynwyd, Ellis and Blay-Miezah would sign new investors to the so-called Oman Ghana Trust Fund. Many were lawyers or business owners who were also promised lucrative contracts with the Ghanaian government, but as "business" continued, college students and elderly widows were roped into the scheme too. All were told that their investment would help Blay-Miezah clear the necessary red tape to bring the money home to Ghana, and that they would be repaid tenfold, perhaps even twenty. When the initial payment date passed, there was always an excuse, a promise of a still greater return and requests for more money.

"I think a lot of the people who ended up investing in the Oman Ghana Trust Fund did know about Ghana or West Africa ... and initially it probably made perfect sense and dovetailed with what they'd heard," Yeebo said. "But as they opened up to a wider and wider pool of investments, I think it was just something that sounded like a good bet to people, who were either feeling greedy or had the money to spare and didn't mind potentially losing it. Or people who really, really, desperately or optimistically wanted to do something with that money.

"I think it just sounded like a grand adventure that would make people a great deal of money and that would let them put their name in lights in this very specific way."

In addition to swindling many Philadelphians out of their money, Blay-Miezah would also marry one city resident to solve his immigration problems and steal college degrees from another — his former roommate Jacob Badu. As prosecutors would later prove in Ghanaian court, Blay-Miezah had contacted Penn claiming to be Badu, asking that his undergraduate and graduate degrees be reissued to him under his new name. All it took was a standard administrative fee.

What eventually ran the con artist out of town was a failed check scam on Girard Bank, the former financial institution. Using blank traveler's checks he obtained from an assistant branch manager, Blay-Miezah made each one out for $50,000 and forged signatures on them. One of his associates would later attempt to cash them at a Deutsche Bank branch in Germany. When both banks caught on to the scheme, Blay-Miezah fled the city and never returned to Philadelphia, spending increasingly more time in Ghana and London courting investors and favors. The assistant branch manager was arrested.

Ellis continued to run the scheme in Philly for years, until state prosecutors caught up to him in 1986. After losing patience with Blay-Miezah's excuses, one of the investors, a Philly lawyer named Barry Ginsberg, had contacted an assistant district attorney for Philadelphia. Ellis was arrested in January and hauled into court that spring, when he stood trial before Judge Lynne Abraham, who, as Yeebo puts it, "carried a gun, drank three cups of coffee a day and was a vociferous supporter of the death penalty." She would become Philly's first female attorney general in 1991.

Prosecutors estimated that the scheme had swindled 300 people in the wider Philadelphia area — though those were just the victims willing to talk, and many of them, amazingly, still believed in the con. They had lost more than $15 million, collectively, a drop in the bucket of the $100 million Blay-Miezah reportedly had scammed from people all over the world.

An arrest warrant was issued for Blay-Miezah, but he already was out of the country. Ellis eventually pleaded guilty and received a sentence of 5 to 15 years in prison. He would be indicted a second time for tax evasion in 1992, the same year that Blay-Miezah died in Accra, the capital of Ghana, while under house arrest. Given his endless spin and many feigned heart attacks, some doubted he was dead until the government obtained fingerprints from his corpse, at the request of the FBI.

Many of Blay-Miezah's supporters still believe the made-up millions are out there somewhere, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It was a scheme that, at various points, involved not just average Philadelphians, but the prominent figures, like nightclub owner Ben Bynum and even John Mitchell, the former U.S. attorney general disgraced by his involvement in Watergate. Everyone wanted to believe in the treasure buried in the Swiss vaults, which could instantly uplift Ghana after years of colonialism and bloody coups and make them fabulously wealthy in the process.

"After you've like arranged your life around something and invested not just money, but also time, it's really, really hard to pull away," Yeebo said. "This has been going on for huge chunks of people's lives, there are children who grew up as part of this organization. And also it would just really be nice if it were true, as ridiculous as it sounds, if there was so much money that Ghana could rebuild itself properly with all the wealth that had been disappeared or stolen from it.

"I think a lot of people held onto it with a kind of religious fervor, like the hope. Not just the greed and the excitement and the adventure and the intrigue of finding out about all this, but also the hope of it carried a lot of people."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.

Provided image/Yepoka Yeebo

Provided image/Yepoka Yeebo