August 12, 2016

Source/phlcouncil.com

Source/phlcouncil.com

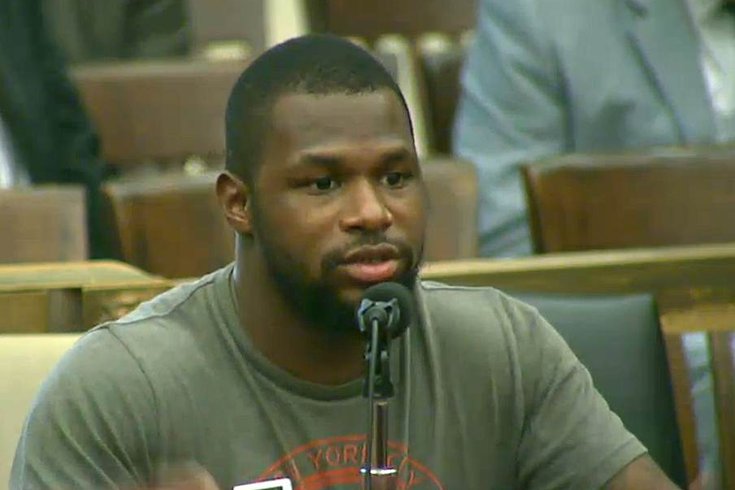

In this screenshot from phlcouncil.com, Joshua Glenn, 28, testifies before Philadelphia City Council's Special Committee on Criminal Justice Reform. Glenn spent 18 months in jail waiting for trial on a charge that was eventually dropped. He and his family couldn't afford the $2,000 bail, he said.

Every day in Philadelphia thousands of men and women languish in jail, yet to be convicted of a crime.

Some have been locked up for a few days. Others for weeks or months, or longer.

They remain behind bars to await trial – jeopardizing employment and housing, for some – because they can't afford bail.

"With a cash bail system, rich people go home and poor people don't," says J. Jondhi Harrell, executive director of The Center for Returning Citizens and a member of City Council's Special Committee on Criminal Justice Reform.

Across the country, cash bail as an institution is being re-evaluated in a drive for pretrial justice. Many cities are asking if it's cost-effective — or, in some cases, even unconstitutional — to lock up individuals for weeks and months as they await trial.

Next year, the state of New Jersey will implement bail reforms. New York City has recently implemented bail reforms intended to reduce the number of people in prison for minor offenses, and Chicago is adopting a new system that would allow those accused of committing non-violent crimes to be released if their cases take more than 30 days to get to trial.

Some are looking to learn from Washington, D.C., a city that hasn't required bail in more than two decades.

Including Philadelphia, which was awarded a $3.5 million grant recently from the MacArthur Foundation to find ways to cut its inmate population by 34 percent over the next three years.

City Councilman Curtis Jones Jr. believes the city can exceed that goal.

He and others are convinced bail reform is the way to do it.

Jones has studied the problem extensively, learned how a no-bail system works and holds a powerful position to help scuttle the current bail system he finds offensive.

"I think we are at a time in Philadelphia where people are coming to the table sincerely wanting to change the criminal justice paradigm," Jones said in a recent interview about bail reform. "We want to get down to like 5,000 [inmates] and we are at 7,500 on average. This alone will do that."

Jones, who represents the 4th Councilmanic District and co-chairs the Council's new Special Committee on Criminal Justice Reform, noted that potentially as many as 70 percent of those 7,500 inmates are being held as they await trial. Many can't afford bail to gain their release.

By significantly reducing its prison population, the city can save big money.

"We are paying roughly $132 to $134 a day for someone who is there only because they can't afford the bail," Jones said.

According to Shawn Hawes, a spokesperson for the Philadelphia Department of Prisons, the city pays somewhere closer to $100 to $110 per day. Hawes noted that the figure can fluctuate depending on variable costs, including inmate medical expenses.

"I have two types of people in my tent: Those who want to save souls, and those who want to save money. These types of programs appeal to both. When you reduce bail, you reduce costs." – City Councilman Curtis Jones Jr.

Jones cites the higher figure of as much as $134 a day, figuring in ancillary costs, like the expenses incurred by the Sheriff's Department, which is tasked with transporting prisoners. That responsibility includes staff and vehicle expenses, he said.

For a city that spent more than $246 million on corrections costs alone in 2015, the huge savings realized by incarcerating significantly fewer inmates could help pay for other needed city services.

"You cannot save city dollars if you don't attack this," Jones said. "I can count all the paper clips in the world I want, but if you don't drill down into the cost of justice and the cost of crime prevention and law enforcement, we're not going to make headway on this."

Jones has a good understanding of the economics of justice. In addition to his work on Council's Criminal Justice Reform Committee, he chairs Council's Public Safety Committee, which has responsibility for police, fire, prisons and the courts – more than a third of the city's entire budget. Gov. Tom Wolf also appointed Jones to represent Philadelphia on the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency.

"I've had a rapid learning curve on this stuff. But I have immersed myself in it," said Jones. "I have two types of people in my tent: Those who want to save souls, and those who want to save money. These types of programs appeal to both. When you reduce bail, you reduce costs."

Reforming the bail system would mean retooling a system that can have a huge impact on the lives of low-income citizens. Many defendants unable to post bail find themselves losing their jobs, educational opportunities or even their homes as they sit behind bars.

Ask Joshua Glenn, 28, of West Philadelphia, who believes the city would benefit immensely from bail reform.

He knows firsthand the damaging effects that the city's current system can have on the lives of young defendants.

In a recent interview, Glenn said the cash bail system robbed him of pivotal moments in his young life.

At the age of 16, he was arrested on a charge of aggravated assault. The charges were eventually dropped, but Glenn spent 18 months in jail waiting for his case to be heard.

According to Glenn, his family couldn't afford bail of $2,000 — 10 percent of $20,000 — in order to get him out.

In that time, he lost a job and missed his high school graduation and his prom.

"I missed out on all the pinnacles of being a young person," he said. "And, when I try to get jobs, that arrest can still show up."

Last week, Glenn had the opportunity to share his story with Jones and the other members of Council's Criminal Justice Reform Committee.

It was a story that Jones took to heart.

"We kept him for 18 months... for $2,000 worth of bail," Jones said. "When you walk in those doors, your life changes, whether you're convicted or not."

Using Jones' figures, Philadelphia paid more than $72,000 to keep Glenn in prison on $2,000 bail.

The Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility on State Road in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia. About 7,500 men and women are incarcerated in the city, and about 70 percent of those are awaiting trial, according to City Councilman Curtis Jones Jr. Many of those are being held because they cannot afford bail.

The day after that hearing, Glenn, Jones and about 15 others, many of them members of the No215Jail Coalition, traveled to Washington, D.C., to see how the no-bail system – in effect since 1992 – works there and help them determine if a similar system can work here.

In the nation's capital, about nine of every 10 people arrested are released within 24 hours. A defendant is never held because he is unable to afford bail.

After an arrest, the individual is evaluated to determine if he is a risk to society or at risk of not showing up for a court date. Then they work with counselors – think a hybrid of parole officer and social worker – and some may be required to undergo drug testing or meet with a pretrial officer.

Defendants charged with violent crimes or sexual offenses could be held for trial without monetary bail or could be released with conditions, depending on a judge's determination considering the defendant's flight risk or if they pose a potential danger to the community. However, Jones said if there are changes in Philly, these types of offenders wouldn't likely be released.

"If it is violent or sexual or those kinds of heinous kinds of things, you're going away, no release. Or, if you're a fugitive, have demonstrated that you're a flight risk, then when you go to jail, you're going to stay there," Jones explained. "But if you're a guy who did retail theft and what really is wrong with you is that you have an addiction, you aren't getting released without consequences. There are consequences to every act. So for you, the judge may say you've got to report to rehab, you've got to be here and you've got to do community service until your court date to stay out."

Harrell, of The Center for Returning Citizens, said that by removing the bail requirement, Washington has reinforced one of the most sacred principles of American criminal justice, that one is considered innocent until proven guilty.

"If we are innocent until proven guilty, then we shouldn't need to have a monetary bond to make that statement," he said.

Harrell, who spent 25 years in prison, mostly for robbery convictions, visited Washington with Jones and met with judges there to discuss how the system works.

According to a recent report in the Washington Post, 91 percent of all individuals arrested in 2015 were released before trial. Of those pretrial releases, 90 percent did not commit additional crimes before their trial dates. Of the remaining 10 percent who were arrested for another crime before their trial date, the overwhelming majority of those offenses were not violent.

In some cases, defendants in pretrial release are found not guilty.

That's why the system is set up so that community service — and aspects of the Day Reporting Center — are voluntary, Harrell said. A defendant can choose to remain in custody to await a court date or voluntarily participate in the pretrial protocol.

"The idea is – would you like to sit in jail or would you like to be out there in control of your life?" he asked.

For bail reform to happen here, Jones said, City Council would need to agree to overhaul the current system. The Special Committee on Criminal Justice Reform was formed to evaluate such a proposition.

"We have the authority to decide if we would require bail or not," Jones said of Council. "We don't have to ask anybody."

Assuming it costs about $134 per day to house each of the 7,500 or so inmates on a given day, the city pays about $357 million annually. Reducing the population by 70 percent – about 5,250 inmates – would save the city about $247 million, taxpayer dollars that could be used to create a system of pretrial services, Jones said.

Jones said he envisions Day Reporting Centers in each of Philadelphia's 48 ZIP codes with counseling staffs and classes to address the myriad issues facing those held in jail.

"The shift is pretrial. We want to start addressing whatever is wrong with you before you actually go to court," he said. "You're never going to fix whatever is wrong with you, if you don't start addressing it now."

After last week's trip, he said, the special committee will meet again, followed by discussions with the full Council. Input from city judges and the city's District Attorney's Office will be solicited, in part, to figure out how such a pretrial system would be implemented.

In an interview Thursday, District Attorney Seth Williams said he would support getting rid of cash bail.

"Oh yeah, 100 percent," Williams said, adding that he'd support a system similar to Washington's. "We've got to try to reduce our prison population in Philadelphia."

But it's an ambitious plan that won't be achieved overnight, Jones said.

"I feel we have to do something different to get a different result. Caution is the watch word; when you start tinkering with things, you need to do a beta test first to see what your results are," Jones said. "So we are going to be slow with it."

Google Maps/Street View

Google Maps/Street View