March 23, 2023

Provided Image/SEPTA

Provided Image/SEPTA

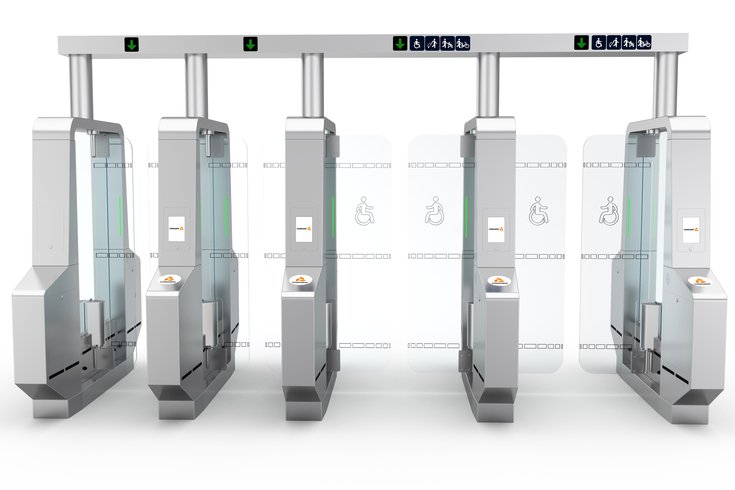

SEPTA will install the fare gates shown above at 13th Street and 34th Street station on the Market Frankford Line in 2024. The new technology is intended to prevent fare evasion, which costs SEPTA an estimated $22.9 million each year.

SEPTA will install new fare gates at 13th Street and 34th Street stations early next year in an effort to stop subway fare skippers. The new technology will be evaluated to decide whether the gates should be expanded across the transit system.

The SEPTA board voted Thursday to test the 8-foot-tall gates, whose glass shields separate after riders swipe their SEPTA Key cards. The height of the gates prevents riders from jumping over, crawling under or skirting past the gates. These are the most common methods fare evaders use to get beyond the metal turnstiles at subway stations.

The new gates will be equipped with 3D-imaging that can detect people and objects that pass through them. Their scanners can distinguish whether multiple subway riders are "piggybacking" on one fare swipe, or if a person is pulling luggage or a stroller. The gates also can tell whether someone is in a wheelchair. SEPTA's existing ADA-compliant gates are often used by groups of people trying to pass through at once.

SEPTA estimates that it loses about $22.9 million annually as a result of fare evasion — about 10.9% of its revenue. About $12.6 million of that loss occurs on the Market-Frankford and Broad Street subway lines.

The estimates are calculated by measuring automated passenger counters against actual revenue, as well as manual fare evasion counts done by staff.

"The Market Frankford Line, just because it's a high ridership line, we see more issues there," SEPTA spokesperson Andrew Busch said.

In the context of SEPTA's roughly $1.6 billion operating budget, losses from fare evasion aren't astronomical. But Busch said they affect a bottom line that's already suffered in recent years.

"It's significant when you look at how our ridership has been depleted through the pandemic, and we're trying to get it built back up now," Busch said. "Overall, we're at about 60% of where we were pre-pandemic. It's important to keep the revenue that we raise increasing so that we're getting everything possible for matching local, state and federal funds."

One of the challenges with fare evasion is that it's difficult to enforce. There are only about 210 SEPTA Transit Police officers, and SEPTA has shifted more of them onto trains and in problem areas to respond to serious offenses.

"Wherever possible, we're trying to use technology to help us with (fare evasion) incidents," Busch said.

Even when people are given citations for fare evasion, SEPTA often struggles to collect the $25 fee, which used to be $300. In cases when SEPTA commits resources to chasing down unpaid citations, fare evaders frequently fail to appear for their scheduled court dates.

Citations dipped from 3,268 in 2019 to 1,948 in 2021, but they rebounded to 2,792 last year. Through February, SEPTA has issued 355 citations for fare evasion this year.

People who fail to pay at least four citations – for fare evasion or other policy violations – can be banned from the system for one year.

Still, this system depends on SEPTA's ability to identify and follow repeat offenders when it's already difficult to catch them at all.

"The other problem with fare evasion is it can be indicative of other problems that might be happening on the system," Busch said, pointing to growing complaints about smoking on trains, thefts and fights.

Other subway systems in the United States are using similar fare gate technology to prevent revenue loss, Busch said. The design SEPTA has chosen for the test program comes from Conduent Transport Solutions, Inc., the same third-party vendor that manages the SEPTA Key fare system. The specific design is currently used as a fare gate by the National Society of French Railroads.

At 13th Street Station, 16 of the new fare gates will be installed, with eight on each platform. Six will be installed on the mezzanine level of 34th Street Station. The contract for all 22 fare gates was priced at $924,950.

SEPTA chose 13th Street and 34th Street stations to test the fare gates for two reasons.

"Those stations were picked, in part, because we do see a significant number of evasion incidents there," Busch said.

The other reason is that the stations' configurations are representative of most others where these fare gates could be installed in the future. They offer a good indication of how the the gates would work elsewhere.