March 10, 2023

Staff photo/PhillyVoice

Staff photo/PhillyVoice

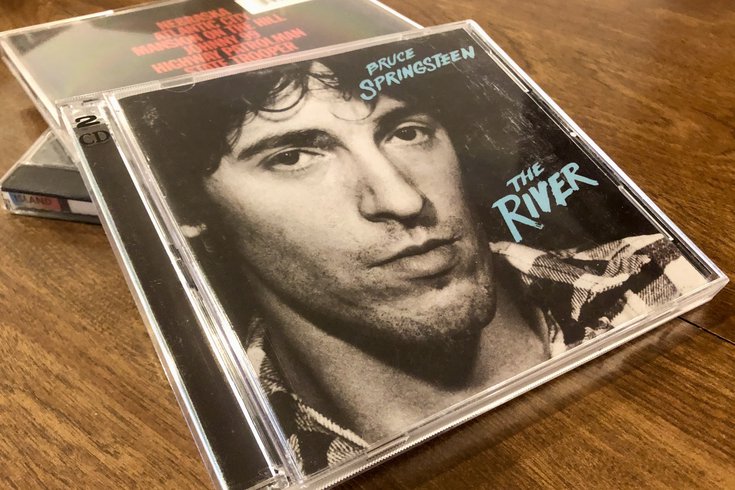

The photo on the cover of Bruce Springsteen's album 'The River' was taken in Haddonfield, New Jersey in 1978, during photos sessions with Frank Stefanko, which also produced the album cover art for 'Darkness on the Edge of Town' and other well-known images of The Boss. Springsteen plays in concert at the Wells Fargo Center on March 16.

In the winter of 1978, Bruce Springsteen drove his Corvette to the quaint borough of Haddonfield.

He pulled up to the home of Frank Stefanko, a meatpacker by day who snapped photos whenever he was off the clock. They'd been introduced by a mutual friend, Patti Smith, because Springsteen needed a cover for his album "Darkness on the Edge of Town," his first in three years, and he wanted something very different from the photo on his last one, "Born to Run," which features the rocker slyly grinning over his guitar.

As Springsteen later recalled in his 2016 memoir, "Frank was a rough-edged, but easygoing kind of guy. My recollection is he borrowed a camera for the day, called a teenage kid from next door to come over and hold up his one light and started shooting. I stood against some flowery wallpaper in Frank and his wife's bedroom, looked straight into the camera, gave him my best troubled young man and he did the rest."

Photos from the Haddonfield sessions, which included later shoots with the E Street Band, landed on the cover of not just "Darkness on the Edge of Town" but "The River" two years later. And for cover of his memoir, Springsteen chose another Stefanko image from those shoots, showing the musician leaning against a front fender of the 1960 Corvette he had just driven to Haddonfield, as it was parked on a snowy street outside the photographer's home. Stefanko has called that photo "'Thunder Road' incarnate."

Stefanko would photograph Springsteen many other times over the musician's legendary, ongoing career — so much so that Stefanko released a limited-edition, 400-photo book in 2017 — but the pictures he captured in and around his home 45 years ago helped define Springsteen's image as a melancholy voice of the working class.

When Stefanko and Springsteen crossed paths, the rocker — who will perform at the Wells Fargo Center in South Philly on Thursday, March 16 — was at a turning point in his career. "Born to Run," his third album with the E Street Band, had been a critical and commercial hit in 1975, but legal battles with his former manager Mike Appel kept him out of the recording studio for three years. He was looking to return with a different sound, something more political and cynical, grounded in his blue-collar background and influenced by everyone from Hank Williams to The Animals.

Not that he told Stefanko any of this.

"I knew what his past music sounded like but I had no idea what intention he had for 'Darkness on the Edge of Town,'" he told Pitchfork in 2010. "I actually didn't hear it until several weeks later. So the original shoot was just done with my perception of how I thought he wanted to look or how I wanted him to look."

On Smith's recommendation — she knew Stefanko from college, and Springsteen from the single they'd just written together "Because the Night" — the two men connected, quickly bonding over their Jersey roots and Italian mothers. Stefanko took Springsteen all over his house, posing him in wicker chairs and up against his bedroom window. The latter location, with its now-famous flowery wallpaper, provided the backdrop for the "Darkness on the Edge of Town" cover.

But Stefanko also took him out in the streets, stopping and snapping photos on the steps of Indian King Tavern, at 233 Kings Highway East, and next to the rotating, striped pole outside Frank's Barber Shop, which closed in 2013. When Springsteen returned with the entire E Street Band, they piled into Stefanko's living room, and crowded a pinball machine at Shellow's Luncheonette in East Camden.

"Frank's photographs were stark," Springsteen wrote in his memoir. "His talent was he managed to strip away from your celebrity, your artifice and get to the raw you. His photos had a purity and a street poetry to them. They were lovely and true, but they weren't slick. Frank looked for your true grit and he naturally intuited the conflicts I was struggling to come to terms with. His pictures captured the people I was writing about in my songs and showed me the part of me that was still one of them."

The house where it all began was sold long ago — and Stefanko told Pitchfork the new owners took down the wallpaper — but nearly half a century later, the images endure, snapshots of a "troubled young man" who could have been anyone, but went on to become one of the most famous rock stars on the planet.

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.