February 12, 2015

ReelBlack TV/via YouTube

ReelBlack TV/via YouTube

MK Asante discusses his book, "Buck: A Memoir," with ReelBlack TV at the Crefeld School in Chestnut Hill in November 2013.

MK Asante has come full circle.

A teenaged drug dealer and delinquent on the streets of "Killadelphia" in the late '90s, his life was changed by a teacher with an open mind and a blank sheet of paper.

It was a challenge he embraced.

A poet, hip-hop artist and filmmaker, he joined the faculty of Morgan State University in Baltimore at the age of 23, and became its youngest tenured professor three years later.

In an interview on National Public Radio, after the memoir's release, he said:

Well, I think first of all, the story is about education. It's about miseducation, reeducation, self-education, street education. It's about the difference and the distance between school and education. Mark Twain said, don't let school get in the way of your education. I learned this firsthand.

Through his creative writing and film classes at the university to his many visits to Baltimore schools, Asante is closing that distance. It's not lost on him.

Two weeks ago, for ThrowBack Thursday, he posted a photo on his Instagram account from the graduate keynote speech he gave at Vassar College last year. "The young buck that got expelled from schools," he wrote, "has now given graduation speeches at #Harvard, #ASU, #UCLA, #UW, etc. Lol oh the irony...."

• • •

Born in Zimbabwe, MK Asante set out to write his story by returning to the state of mind he had as a black teen growing up in North Philadelphia.

“Philly is a state of mind I’m always in. The city is truly a character in its own right, and it’s served me well because the people I was exposed to gave me that cultural rootedness.” – MK Asante

His older brother was imprisoned in a faraway state. His mother and his sister each suffered from a debilitating mental illness. His father, a trailblazing Temple University scholar who developed the theory of Afrocentricity, struggled to meaningfully connect with him. Asante’s deepest attachments were to the intrepid pulse of hip-hop and the knowledge he found entrenched in Philadelphia’s streets, stolen cars and flirtatious subways.

“Taking that perspective from 15-plus years ago and turning it into a present-tense narrative was one of the biggest challenges of writing Buck,” Asante, now 32, said. “It’s not just anyone, it’s me, but I was looking at it from the vantage point of a kid."

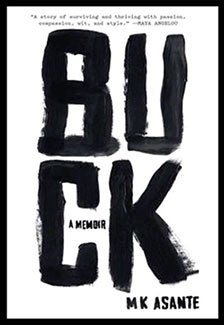

Buck is Asante’s unapologetic expression of how grappling with the pressures of race and class in urban America became a springboard for greater appreciation of his roots. In the span of 45 lyrically charged chapters, narrator Malo splinters the surfaces of family turmoil, anatomizes Olney’s urban decay, and chronicles a truant drift through schools until Asante arrives at Chestnut Hill’s Crefeld School, where he finds his calling in life to write.

The Crefeld School in Chestnut Hill, where a teacher challenged MK Asante to write his future.

“Philly is a state of mind I’m always in,” Asante maintains. “The city is truly a character in its own right, and it’s served me well because the people I was exposed to gave me that cultural rootedness.”

The memoir has garnered accolades, from 2014’s In the Margins Book Award to the Sundance Institute’s Feature Film Program Grant. Still, Asante says his proudest honor has been to take what he learned from Philly and use it to strengthen and free young minds.

“Living uptown, in Germantown, in Oak Lane, Olney, all of these experiences taught me a lot about people,” he said. “Going back to that for a project like Buck made me realize—okay, I need a book that will not only be useful for academics, as a teaching guide, but that a kid on Erie Avenue will pick up at Black and Nobel, read it, and go, ‘Oh, s--t!’—and it changes his life. I had to know—is that even possible?”

For a book that freely quotes Tupac lyrics, reviews the art of twisting a blunt, and takes its narrator’s nickname as an acronym for Me Against Law & Order (MALO), high school classrooms might seem an unlikely landing place.

Certain educational settings have become a home for Buck, however, in part because wizened teachers realize that their students can better identify when narratives speak the language of both b.s. and serious business.

“I’ve never met anyone who connected with every single one of our scholars in a way that was not only genuine, but based on his work engaging them. This is the impact of him showing his commitment to the youth of tomorrow." – Chelsea Kirk, educator at Maya Angelou Academy

Nate Brown, who works with the PEN/Faulkner Foundation’s Writers in Schools Program, coordinates visits by local authors to schools in Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. Brown has organized more than a dozen high school visits with MK Asante since 2013, donating copies of the memoir to English students at the request of their teachers.

“We’re trying to engender, through interaction with students, a genuine attachment to reading,” Brown said. “That sounds sort of nebulous, but in using a book like Buck, especially in a school with a predominantly African American population, it resonates. Not just because of the demographic similarities, not just because North Philly is somewhat like East Baltimore, but because culturally many of these students find it familiar.”

Though MK attributes Buck’s triumphs to the legacy of hip-hop binding politics with poetics, he also knows that the realities of contemporary American life give his memoir added currency. With racial awareness and tension higher in the United States, classroom discussion about a book like Buck helps establish a tone for confronting the issues a younger generation is inheriting.

MK Asante signs books for students following their class discussion at Academy of College & Career Exploration in Baltimore's Hampden neighborhood in December 2014. (Photo by Nate Brown)

“Students are most often interested in the rarer experiences MK has, like film production or playing basketball at Lafayette,” Brown continued, “but MK also can guide the conversation into serious terrain.”

Brown recalled a particular visit to Northwestern High School in Baltimore last fall, when the discussion turned to passages in the book that examine the problem of racial profiling. Asante’s back-and-forth with students led to a broader talk about the meaning behind protests for justice in Ferguson.

“When a group of 15-year-old African American sophomores are talking about racial profiling,” Brown said of the visit, “what they’re assuming isn’t, ‘Does it happen?’ but rather ‘when and how?’ It was a deeper and more nuanced conversation about what it means to be young and black in the United States.”

For Asante, this is, in many ways, what sets his story apart. By his own careful admission, the upbringing he had was more or less middle class, enabling him to attend a private school like Crefeld. How he wound up posted on corners went beyond socioeconomics. While his racial background undoubtedly influenced his frustrations over inequality, Buck suggests Malo’s struggles were just as much a reaction to family heartbreak.

It’s a theme anybody can relate to, and yet one so puzzlingly overlooked when trying to trace hostility and destructive behavior in people—regardless of race or income. When Asante’s writing deals with drugs, sex and violence, his intention isn’t to endorse or glorify, but to depict real scenarios that carry the consequences of choices made in life.

“How Buck teeters the line goes beyond whether it’s appropriate or inappropriate,” said Chelsea Kirk, an assistant principal and English teacher at Maya Angelou Academy, a D.C. transitional facility for youth who have committed crimes. “The fact that it’s raw and breaks boundaries of aesthetics helps it accomplish a crossover in how this kind of story can be told.”

“I feel like the least I can do is provide that same support to young people who are coming up now,” Asante says. “Maya Angelou told me that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle. Sometimes we feel like it might diminish us, but it really doesn’t.” (Nell Redmond, File/AP)

Asante visited the school twice in December, and Kirk was awestruck by his willingness to talk openly about life with her students, approaching them all as adults. She found that MK’s interest in learning from them was every bit as strong as their desire to know him.

Based on those visits, Buck became a model to help guide Kirk’s students in writing their own memoir assignments, taking ownership of their own life stories without feeling shunned or stigmatized.

“I’ve never met anyone who connected with every single one of our scholars in a way that was not only genuine, but based on his work engaging them,” Kirk said. “This is the impact of him showing his commitment to the youth of tomorrow. He truly believes in these intergenerational changes and the place of these kids being fundamental to what his work represents.”

If MK Asante’s time spent in schools is a testament to anything, it’s his appreciation for those who formerly inspired and mentored him. As a graduate student at UCLA, he reached out to the late Maya Angelou, who enthusiastically offered to collaborate with him as the narrator of his 2008 Kwanzaa documentary, The Black Candle.

“I feel like the least I can do is provide that same support to young people who are coming up now,” Asante said. “Maya Angelou told me that a candle loses nothing by lighting another candle. Sometimes we feel like it might diminish us, but it really doesn’t.”

“I see that growing up in Philadelphia is the basis for me being able to speak to so many audiences,” Asante says. “Whether it’s in a prison or in a university, people see pieces of Buck that mean something to them.” (Photo by Lee Steffens)

Ultimately, this is what makes Buck so forceful in conveying Asante’s devotion as an artist and emerging role model. The crossroads of his own adolescence was about choosing whether to rebel constructively, through art, or forfeiting his powers of observation for a life left unattended. The memoir plays with fire not by fanning flames of contempt, but by voicing the kinds of messages that reach toward universality, love, knowledge, and generosity—even when the truth in between them hurts.

For this, he credits Philadelphia’s unique history of social confrontation and compromise, which repeatedly gives rise to greater understanding.

“I see that growing up in Philadelphia is the basis for me being able to speak to so many audiences,” Asante said. “Whether it’s in a prison or in a university, people see pieces of Buck that mean something to them.”

As Asante adapts his memoir into a Sundance film in the coming year, his schedule will include further visits at schools. By popular demand, he may need to find his way up I-95. In a touching, yet routine example of the book’s impact, Asante shared a note he received from a student at Philadelphia’s Mastery Charter School-Thomas Campus:

I just wanted to say thank you for being an inspiration to not only African American boys but also young teenagers everywhere, especially in Philly…I hope I can hear one of your motivational speeches one day.

Kirk said a visit here by Asante would inspire students in his hometown.

“I feel fortunate and lucky that my students have had the opportunity to meet someone who is such a successful author, activist and advocate,” Kirk said. “An underlying message at our school is that things don’t come easy, nothing comes easy. For our students, MK defines and personifies hard work.”