January 18, 2017

U.S. Naval Historical Center/PROVIDED PHOTO

U.S. Naval Historical Center/PROVIDED PHOTO

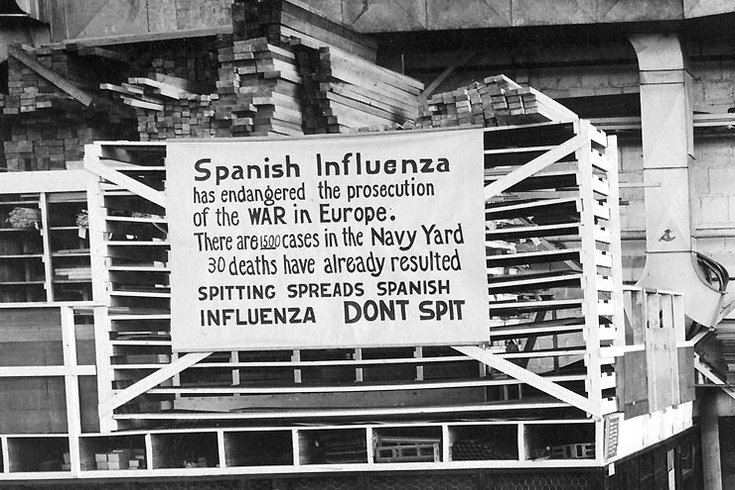

One of the main entry points for the 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak to Philadelphia were sailors from overseas returning home through the U.S. Navy's shipyard in Philadelphia.

Flu kills. Not so much during the 2016-2017 season, which is peaking in terms of numbers in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, yet remains relatively mild in terms of severity, according to the city’s health department.

But 99 years ago, Philadelphia was the epicenter for the one of deadliest diseases in history.

Around the world, the Spanish Influenza outbreak of 1918-1919 killed as many or more people in a few months than the Black Plague did in years.

Flu infected about half the world's population in 1918, killing 50 million people globally. Some estimates put the death toll at as many as 100 million. More than 25 percent of the U.S. population became sick. About 675,000 Americans died.

But the hardest hit place worldwide was Philadelphia.

The city had more than 47,000 reported cases. More than 30 percent of the city’s 1.6 million residents contracted flu.

In fewer than five weeks, from September until early November 1918, more than 12,000 Philadelphians died – meaning more than 25 percent of those who contracted the flu in the city died, a far greater percentage than elsewhere.

Public places – such as churches, schools, and bars – closed as officials struggled to get a handle on the outbreak. Camden, on the other hand, kept its bars open, and Philadelphians crossed the river in droves. Camden eventually closes its bars, too, worried about the spread of the disease. Some local businesses closed voluntarily, others loaned their delivery trucks to authorities to offer assistance.What made the flu so devastating, especially in Philly?

First, there was the science.What exactly caused the flu remained unknown because the study of viruses was still in its infancy; viruses were so small they could not readily be filtered, seen and examined. Scientists did not identifying the correct virus causing influenza until 1933.

Karie Youngdahl, of the Philadelphia College of Physicians’ “History of Vaccines” site, said mistaken efforts to immunize patients against bacteria at least clarified that a virus was the cause of flu. (The College of Physicians of Philadelphia is making plans for an anniversary exhibit on the outbreak.)

But that doesn’t explain: Why Philadelphia?

Stacey Peeples, the curator of Pennsylvania Hospital's Historic Collections, has answers drawn from the archives of the oldest hospital in the country.

There was the military fighting World War I, troops crammed in close living quarters, around-the-world military movements, Peeples said, and the deployment of the majority of Pennsylvania Hospital's medical personnel to a hospital in France.

Sailors, assigned overseas, brought the virulent strain of the disease from Europe in the fall of 1918, first to Boston, then to the U.S. Navy Yard in South Philly.

On Sept. 28, 1918, sailors and soldiers mixed among citizens as 200,000 people turned out for a Liberty Loan Drive parade on Broad Street.

Within days, more than 600 people in Philadelphia had contracted the disease.

A Liberty Loan parade and rally to raise money for World War I down Broad Street on Sept. 28, 1918 helped spread flu from sailors to the general population of Philadelphia.

The University of Pennsylvania, which now operates Pennsylvania Hospital as a part of Penn Medicine, got hit especially hard. Many of its students, living in close quarters in a military officer training program and in dorms, contracted the flu.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania Hospital – understaffed because so many doctors and nurses were in France – treated the first wave of sick sailors. Peeples said two nurses and an ambulance driver soon died from the flu.

In the coming days, an average of 28 nurses on any given day were stricken with flu, further reducing the medical personnel available. And there simply were not enough beds available, meaning the hospital accepted only the sickest patients.

Nursing students were pressed into service at the hospital, Peeples said, and they were soon augmented by untrained volunteers from the community. But infections “snowballed.”

Burial were not taking place fast enough to keep pace with the rate at which people were dying — sometimes hundreds awaited burials.

Then at the end of October, the disease suddenly eased up in Philadelphia. Churches reopened on Oct. 27, with other public places soon following. Many believe the virus mutated, causing it to spread more slowly, become less deadly.

By February, the Spanish influenza pandemic was at an end worldwide.

U.S. Naval Historical Center/PROVIDED PHOTO

U.S. Naval Historical Center/PROVIDED PHOTO