July 26, 2023

Thom Carroll/for PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/for PhillyVoice

Hotter temperatures, due in part to the urban heat island effect, force Philadelphians to seek relief in the shade, pool or public fountains.

The urban heat island effect is making the scorching summer significantly hotter, according to new research from Climate Central.

On Wednesday, the nonprofit released an analysis of the urban heat island effect, or the increase in temperature due to roads and other heat-absorbing infrastructure, in 44 major U.S. cities. It found that 38% of Philadelphians experience a temperature increase of 8 degrees Fahrenheit or more due to the effect, meaning that when it's 92 degrees outside, it really feels like 100.

Some city residents suffer even greater temperature spikes. Climate Central estimates that 18% of the population, nearly half a million people, experience an increase of 9 degrees or more. Almost 194,000 residents, or 8%, experience an increase of 10 degrees or higher.

"Some cities are exposing considerable numbers of people to that 10 degree temperature departure because of the urban heat island effect," said Peter Girard, vice president of communications for Climate Central, who includes Philadelphia in that category. "For what it's worth, under eight degrees is still potentially significant and still enough to create a different profile of human health risk. But especially with large cities, when you look down at five and six degrees, the percentage of people exposed to that level of temperature lift is really high, in some cases close to a hundred."

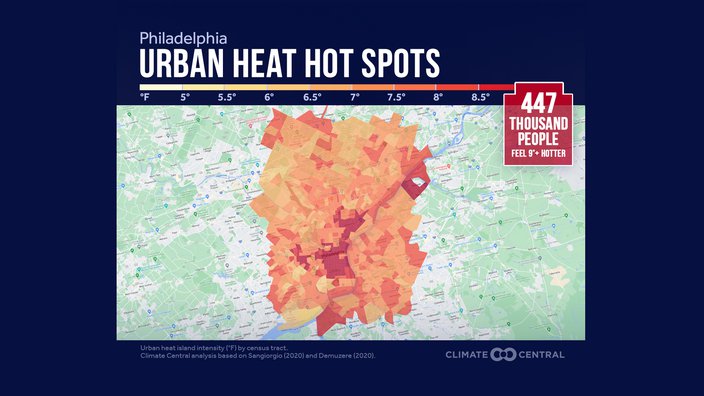

Climate Central found that the heat was the concentrated in "a distinct urban core" comprising Center City, South Philly, Kensington and parts of West Philadelphia, as illustrated in the map below. More developed areas tend to attract more heat intensity due to their blacktops, taller buildings and lack of green spaces. But Girard says Philadelphia's old, narrow roads may also be a contributing factor. The Schuylkill River might be, too, since bodies of water tend to have low albedo — meaning not much sunlight is reflected.

Provided image/Climate Central

Provided image/Climate CentralNeighborhoods experiencing the biggest temperature increases from the urban heat island effect are shaded in dark red.

The analysis was based on 2020 U.S. Census data. Using modeling developed in a previous study, Climate Central researchers calculated an urban island heat index value for each neighborhood based on tree coverage, building density and other factors.

Philadelphia did not crack the report's top urban heat rankings by total area, but it did when the averages were weighted by population. Philly tied with six other cities for seventh place in that ranking, with an average UHI index of 8 degrees Fahrenheit. It was beaten by Los Angeles, Seattle, Miami, Chicago, San Francisco and New York.

These temperature increases can put city residents at higher risk of heat stroke, Girard says, and could worsen preexisting conditions. "It places more stress on the very young and very old," he continued. "It also increases cooling costs. When you're exposed to these areas where you've got amplified heat because of the urban heat island effect, it simply costs more to keep buildings and public space is cool."

Rooftop gardens and cool roofs or pavements made of reflective material can lessen the urban heat island effect. So can planting trees, which Girard calls "one of the easiest interventions that cities can take." But Philadelphia has struggled to maintain, let alone increase, its arsenal of street trees over the years. The city's tree coverage actually decreased by 6% between 2008 and 2018, despite a citywide goal to increase it by 30% across all neighborhoods by 2030. Last year, Philly lawmakers imposed fees on developers who cut down trees without a plan to replace them.

Bringing down the heat will take more than a few trees, Girard says. Without serious climate solutions, he argues, temperatures will only continue to climb, as will health risks. Each year, an estimated 1,300 people in the U.S. die from extreme heat, which is considered deadlier than hurricanes, floods and tornados combined.

"People living in cities, which is a high percentage of people around the world and certainly in the U.S., are exposed to amplified effects of climate change," he said. "And even though these solutions can help reduce the effect of the urban heat island effect in their neighborhoods, the only persistent long-term solution to keeping people in our cities who are feeling more of this heat safer is reducing the effects of climate change. That means reducing emissions and confronting and hopefully reining in global warming."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.