April 29, 2015

Bryan Woolston/For PhillyVoice

Bryan Woolston/For PhillyVoice

Cathy Messina of Warminster came home last year to find two of her sons overdosing on heroin. Her son, David, died. An older son survived and is clean now.

It’s been more than a year, but the memory of the night Cathy Messina returned home to find two of her sons overdosing on heroin remains a fresh wound.

RELATED STORY: A South Jersey man's journey from pills to heroin

She found David, 21 at the time, first, on the bathroom floor after he overdosed in their Warminster home. She ran upstairs, screaming for David’s older brother. She discovered him lying prone on his bed, also unconscious. Two of her five sons had overdosed that February night.

At one time, heroin’s primary clientele was urban black men, but that's an antiquated image. Now statistics show that 90 percent of teen heroin addicts are white. The drug and its prescription-pill incarnations are invading predominantly white suburbs.

The older brother, who Messina asked not be named, is clean now. But David never came home from the hospital.

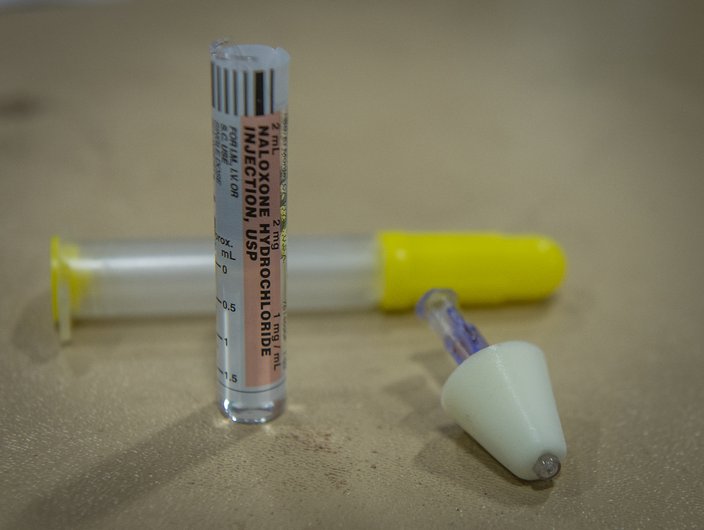

Last week, Messina stood before fellow parents of addicts at the St. Robert Bellarmine Church gymnasium, in Warrington, relaying the story of David’s final days as a harbinger to those whose sons and daughters still live. Messina has launched a program in Bucks County, in partnership with Prevention Point Philadelphia, which trains family members to administer Nalaxone, an anti-overdose drug.

Heroin tore a chasm in her family, and she’s helping other families avoid the same fate.

Heroin is stealing children away. It’s the monster that snatches them in the night, shackling them in prison and burying them in cemeteries. And the Messinas are among thousands of parents across the country who must face that fear daily.

While rates of addiction and overdose death are skyrocketing, no demographic is succumbing more severely than young adults. More than 1,200 Americans aged 18-24 died in 2013 from drug poisoning involving heroin, compared to only 210 in 2000. The number of teens seeking treatment for heroin abuse has jumped from 4,414 in 1999 to more than 21,000 in 2009, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reports.

In Pennsylvania, it seems the problem is worse. Heroin/morphine are the No. 2 most frequently detected drugs for mortality cases with a presence of narcotics, 36.8 percent, in Philadelphia. While the city has certainly seen the most overdose cases in the state, the suburbs are catching up: Heroin and other opiate-related accidental drug deaths in Bucks County rose from 56 in 2008 to 97 in 2011. Montgomery County has faced a similar fate, with 83 drug-related deaths in 2009, compared to 134 in 2013. Heroin deaths more than doubled in the same time, from 20 to 46 deaths.

At one time, heroin’s primary clientele was urban black men, but that's an antiquated image. Now SAMHSA reports that 90 percent of teen heroin addicts are white. The drug and its prescription-pill incarnations are invading predominantly white suburbs, making their rounds through high school halls and college parties.

Cathy Messina tells fellow parents how heroin tore her family apart. (Bryan Woolston / For PhillyVoice)

“David didn’t fit the stereotypical person who uses drugs,” Cathy Messina says. He grew up in a stable suburban community and household, with both parents present. He played high school football. He wasn’t a troublemaker and he didn’t have an attitude.

“He was always smiling,” she says fondly.

Talk to parents whose children have succumbed to drug addiction, and their response is textbook: He was a good kid. He was the star of his soccer team. Everybody liked her. She always seemed so happy.

It’s those same “good kids” who end up aimlessly wandering Kensington’s alleyways, strung out after a rendezvous with their dealer. Or with a litany of bench warrants for drug paraphernalia. Or six feet under.

America’s “good kids” are hiding dark secrets.

In Messina’s class, Drug Addiction oVerdose Education, or D.A.V.E., families are fraught with worry, coming to terms with the idea that their kids can be both good and addicted.

While parents busy themselves checking under the bed for usual monsters – the “wrong crowd” of friends, criminal acts or sexual activity – teens and young adults are most often falling victim to addiction, exacerbated by the swath of mental-health issues that develop at a young age: depression, anxiety, anger. Addiction is the chronic disease that helps them cope, and heroin is the brief albeit euphoric high.

Some parents, like Messina and her husband, Christopher, knew their son’s demons. They checked David into a treatment program, and in his final days, he was on lockdown in their home. Still, Cathy Messina attributes his overdose to anxiety.

“I think he was desperate,” she says, adding that David had a court date scheduled just two days after the day he overdosed.

“I don’t want to have to tell a 4- or 5-year-old that mommy’s never coming back again.” – Margie, talking about her daughter, a mother and an on-again-off-again heroin user for 12 years

“Dave was a charmer, he was such a nice person,” his father recalls. “[But] there was something not right about his thinking process.”

Other parents, Messina says, are naive. "'My kid tells me everything,'" she says, quoting fellow moms. “No, they don’t. People want to believe that, so that’s what they say.”

She and her husband believe the only way to combat youth addiction is education. Which is why she and family friend Denise Frattara are hosting D.A.V.E. classes in Bucks County.

“This is kind of helping me with Dave,” Cathy Messina says. “I feel that Dave is beside me, and this is helping me make it through each day, and not feel sorry for myself. If I can help somebody else, by putting a smile on their face or saving someone’s life, it’s like I saved Dave.”

Margie, whose 30-year-old daughter has been an on-again-off-again heroin user for 12 years, was part of the anxious and hopeful crowd in the gymnasium. Her daughter, currently pregnant, is receiving treatment at a methadone clinic, but Margie fears the day she returns to the drug postpartum.

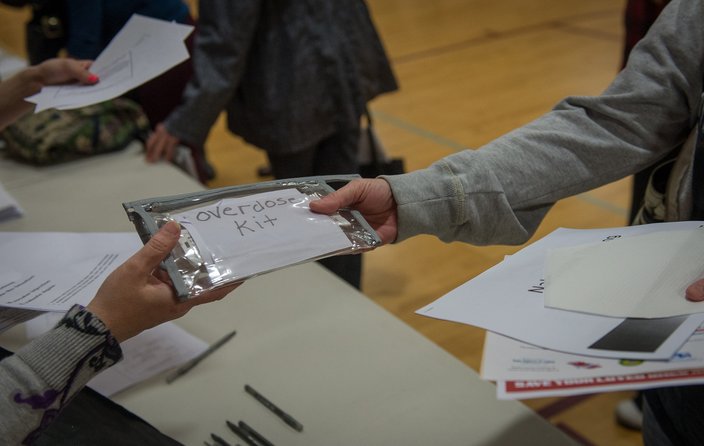

“I hope to God she doesn’t go back (to using)," she says, asking that her last name not be used. But "just in case she does go back,” Margie attended Messina’s Naloxone administration class and waited to get an overdose kit, which contained needles, vials of the anti-overdose medication and instructions.

A used vial of Naloxone. (Bryan Woolston / For PhillyVoice)

“She has had guns held to her head, she went through all the horror stories,” Margie says of her daughter, a mother who has overdosed many times previously. “It’s horrible, because I have her kids. And, it’s just like a nightmare.”

“Right before she got pregnant this last time, she was found in the middle of a parking lot just laying there,” Margie recalls.

The toll on the family is “horrendous,” says Margie’s daughter-in-law, who declined to give her name.

“It’s a worry, it’s a wonder, it’s anger, it’s fear, it’s … when you get a call at 2 in the morning, is someone sick or do I have to go find her,” she explains.

Margie said while the stigma of heroin addiction used to be “hush-hush,” it’s coming more into the light. But that stigma doesn’t stop her from her main priority: saving her daughter.

“I’ve called the cops on her, I’ve had her 302’d, just to get her off the street,” Margie says. “I wasn’t taking it anymore, I was doing whatever I could to have her locked up or committed.”

“I don’t want to have to tell a 4- or 5-year-old that mommy’s never coming back again.”

Veronica Bills’ son, Blake, is serving 17 years in a maximum security Pennsylvania state prison after his infamous heroin-propelled “Bonnie and Clyde” crime spree in Camden and Philadelphia in 2013. She is the sole caretaker of Blake’s daughter, who was born only months before Blake and girlfriend Shayna’s interstate binge.

Watching the news unfold that March day last year, when her son and his girlfriend stole two police cars and took Pennsylvania and New Jersey police on a chase made for the movies, Bills said she thought her son was dead.

“Panic. Hysterics. I was screaming and yelling and crying,” she said. “I still cry every day.”

Now, lawyer and prison fees are crushing Bills, who currently lives in Pilesgrove, Salem County. Prison isn’t free, she says. Blake is locked up, but she’s the one footing the bill. She puts $150 each month on his phone card, and $200 a month toward his commissary.

“From a family’s perspective, it’s devastating,” she says. “It’s ruined our lives … Financially, it has destroyed us. I’ll be paying … until 2027. I’ve already paid $100,000.”

“We’ve got the baby, that’s a whole new thing with financials,” she adds.

Blake Bills is serving 17 years in a Pennsylvania prison after a heroin-fueled crime spree in Philadelphia and Camden in 2013. (Source: Change.Org)

Then there’s the worry about his safety.

“Is he getting raped, is he OK, is he getting beaten up,” Bills says. “I’ve seen him ... his hands have been bloody, he’s had black eyes, his arms have been beaten up. To go through this, and to think he’s going to be there for 17 more years.”

But more than anger, more fear or worry, more than self-deprecation, more than shame, these parents yearn. Yearn for their sons and daughters to return home, to sit at the dinner table. For more hugs, more "hellos," more holidays. For their younger children to not follow the same fate. For the chance to go back and do it all differently.

“I would’ve taken him away with me,” Christopher Messina said about his son. “I would’ve taken him anywhere, just to get his mind right.”