June 28, 2018

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

John Kopp/PhillyVoice

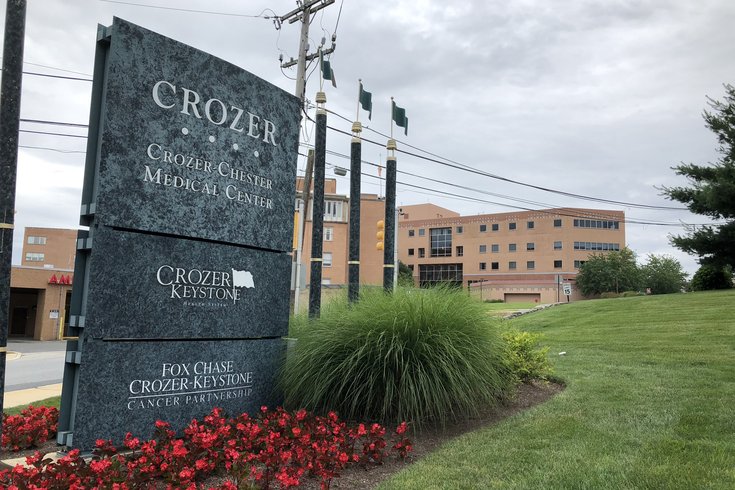

Crozer-Chester Medical Center in Upland, Delaware County, houses one of 45 so-called "Centers of Excellence" designed to engage people battling opioid addiction in Pennsylvania.

Crozer-Keystone Health Systems has engaged more than 1,000 people battling opioid addiction since opening its Center of Excellence, a full-service case management program launched in January 2017.

That milestone reflects two major factors – the considerable outreach efforts made by Crozer-Keystone and the grave state of the opioid epidemic, which continues to claim thousands of lives in Pennsylvania each year.

"We are one of the most busiest, robust centers," said Dr. Kevin Caputo, Crozer-Keystone's vice president of behavioral health. "We have engaged people in treatment – both inpatient and outpatient. It has been highly successful in what I call the opioid war."

Gov. Tom Wolf's administration has funded 45 centers of excellence since 2016, an attempt to help more people receive treatment for opioid addiction. More than 19,000 people have interacted with those 45 centers, with 68 percent engaging in some form of treatment.

Prior to the creation of the centers, only 48 percent of Medicaid patients diagnosed with opioid use disorder received treatment, according to the Department of Human Services. And only 33 percent of those patients remained in treatment for more than 30 days.

Crozer-Keystone's center includes a First Steps Treatment Center, a 52-bed facility that provides both inpatient hospital and nonhospital services, including detoxification, treatment and rehabilitation.

The residential facility at Crozer-Keystone Medical Center in Upland, Delaware County, is so frequently filled that another 27-bed facility is being built at Delaware Memorial Hospital in Upper Darby, Caputo said. The new facility is expected to open within the year.

"When we opened the (First Steps) unit in March 2017, within a week we were full – both the downstairs and the upstairs," Caputo said, noting the different sections of the facility. "That was partly because of the Center of Excellence engaging people, saying 'We have treatment ready for you,' and partly because of the whole epidemic."

Caputo relayed those housing challenges to state DHS Secretary Teresa Miller, before she toured the facility Wednesday morning.

"Housing seems like it's a huge issue," Miller said during a 40-minute meeting with Crozer-Keystone officials, including Chief Executive Officer Patrick Gavin. "Everywhere I go, I hear about that."

Source/Crozer-Keystone Health Systems

Source/Crozer-Keystone Health SystemsPatrick Gavin, chief executive officer of Crozer-Keystone Health Systems, greets Teresa Miller, secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, prior to touring the First Steps Treatment Center at Crozer-Chester Medical Center.

Crozer-Keystone's residential facility is supported by nearly $1 million from Delaware County. It also receives a $50,000 annual grant from DHS.

That grant has been used to deploy staffers to emergency rooms around the clock, meeting with people who have been admitted for opioid-related issues, Caputo said. The idea is to remove one of the biggest barriers the patients face – asking for help.

The "golden time" to reach people battling addiction is when they are in the emergency room following an overdose, Caputo said. The staffers include three certified recovery specialists and a registered nurse who work to keep people in treatment by coordinating follow-up care and community supports.

"A lot of our outreach involves almost hand-holding," Caputo said during a 40-minute meeting with Miller. "Because, as you're aware, many of our addicts are ambivalent about treatment. They (think) they don't need it. They don't know about it. They're confused. They're scared.

"Our team is informative, gentle, kind and most importantly facilitates that transfer easily. Any barrier you put up for an addict is going to get in the way of treatment. ... They remove the barriers."

The state's Centers of Excellence are designed as so-called "hub and spoke" networks, with the center serving as the hub and an array of referral sources – primary care providers, social service agencies and the criminal justice system, among others – serving as spokes.

At Crozer-Keystone, patients also have access to programs that assist expectant mothers who have substance abuse disorders – and their unborn babies. The medical center regularly treats babies with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, a condition in which a newborn experiences withdrawal after birth.

"Addiction is a disease," Caputo said after the meeting. "It's not a moral failing or a weakness. And we need to treat it like we treat hypertension and diabetes. Our role in behavioral health is to make it as easy as possible for people with the disease to get that treatment."