December 12, 2017

Shortly after the Barrymore Awards in late October, Philadelphia playwright Ozzie Jones took to Facebook to blast organizers for failing to mention local actor Michael Leland II in the annual memorial, saying black artists are all too often overlooked – if included at all – in the theater gala.

“To quote Ice Cube,” he wrote, “here’s what they think about you.”

The omission, which echoed loudly throughout Philly’s theater community – and particularly on social media threads – inspired Jones to join several other men of color in the arts to talk frankly about their experiences with race, diversity and inclusion on a special podcast of RepRadio.

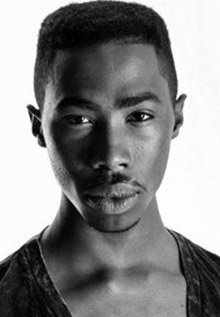

Terrell Green, a writer, performer and educator, says there are few opportunities for people of color in Philadelphia’s theatre community.

One of the guests on the show, Terrell Green, admitted to PhillyVoice a week earlier, “I feel used.”

Green, a writer, performer and educator in his 20s, says there are few opportunities for people of color in Philadelphia’s theater community. As such, he often writes and produces much of his own work, including his most recent show, “Blackberry,” which featured an Iranian character. Despite the enormous effort required to create and produce a show independently, he said it’s easier than trying to get the attention of mostly white theater producers in the city.

“I’m not seeing stories like mine being told on stage,” Green said. “So I’ve got to be the change agent. There’s a real responsibility now more than ever. And what we do really matters.”

Wayland Harris, an actor in his mid-30s with film and musical theater experience, agrees with Green, admitting that he spends most of his time working in New York City because there simply aren’t enough roles for black actors in Philly. Add to that the challenges he faces because he wears his hair in braids and cornrows, and the few roles that do exist tend to dry up.

“I often hear the usual ‘you’re not what we’re looking for’ from directors,” said Harris, who recently starred in “High Energy,” an off-Broadway musical. "More roles go to white people.”

For example, in January when Harris showed up to an open casting call at one of the largest theater companies in the city, he never actually had the chance to audition. “It deterred me,” he says.

And during another audition, one where he actually made it in front of the director, he was asked to cut his hair, as he explained, “so the director could try to see me in the role.”

Harris declined, saying he would not change his look unless he got the part. “I can’t begin to tell you how many times I hear things like, ‘I just can’t see you for this role,’” he said, “unless it’s for a drug dealer.”

The Barrymore Awards recognize excellence in theatre produced in the Greater Philadelphia area.

The Barrymore Awards for Excellence in Theatre are presented annually by Theatre Philadelphia for productions in the Greater Philadelphia area. Leigh Goldenberg, the new executive director of Theatre Philadelphia, admits the group has come under fire recently for lack of diversity, particularly during the most recent awards show, which was dominated by mostly white actors. Goldenberg says she is working to change the dynamic by rethinking who is nominating shows and actors citywide.

After conducting a survey of all Barrymore nominators, Theatre Philadelphia was struck by how many were straight white men.

“Upon surveying our nominators for the 2016-17 season,” Goldenberg explained, “we found that 15 percent were people of color and 15 percent were LGBTQ. We set a goal to reach 40 percent diversity for the 2017-18 season, meaning that 40 percent of our pool would be either a person of color, LGBTQ or gender non-binary.”

“It’s a conversation we’ve been delving deeply into on the board level.” – Jason Lindner, Theatre Philadelphia board member and Interact marketing director

Through outreach online and in person, she says Theatre Philadelphia has since received about 135 new applications. To date, about 33 percent of the 2017-18 nominators and judges are white and heterosexual. “We exceeded our goal of 40 percent to get to 67 percent of our pool with at least one diversity metric,” Goldenberg said.

The new pool includes 56 percent women, 38 percent men and 6 percent non-binary or gender fluid people. “We have 36 percent people of color,” she said.

“It’s a conversation we’ve been delving deeply into on the board level,” said Jason Lindner, a Theatre Philadelphia board member and marketing director at Interact Theatre Company. He admits a big issue on the table now has to do with the gender divide, namely how non-binary or gender fluid performers can and will be honored if Barrymores are only awarded to in best actor and actress categories. Lindner expects to see more gender fluid categories soon, especially as more productions are written and star transgender and gender non-binary artists.

Working with the Ghostlight Project, which designated theaters as safe spaces after the election of Donald Trump last year, has also inspired more Philly theater companies, said Lindner, to rethink how this translates in terms of diversity. “It’s all about accountability,” he said. “Believe me when I say we are attempting to have these conversations.”

And while representation at the Barrymore Awards level will likely help to spotlight more diverse performers and projects in the next few years, there remains a big question on the minds of many writers, directors and performers who feel left out of the conversation now: will people of color be cast in more productions, and if more diverse stories can ultimately be told on stage, will audiences show their support?

Leigh Goldenberg, the new executive director of Theatre Philadelphia, is seen during the Barrymore Awards presentation in October. She admits the group has come under fire recently for lack of diversity, particularly during the awards show, which was dominated by mostly white actors.

In an era when a musical like “Hamilton” – the immigrant story unconventionally cast across race lines using hip-hop – has broken records and won fandom and awards, one might expect the theatre world begin to embrace far less conventional notions about what works on stage, especially if it hopes to woo younger audiences. But there are challenges in a city as old, and as traditionally steeped as Philly. But that doesn’t mean the conversations aren’t happening among some of more progressive theater leaders.

Seth Rozin, the founder and artistic director of InterAct Theatre Company, says diversity is very much on the minds of his peers within the Philly community, both in terms of casting and productions, as well as staff at local theater companies.

One of the things he has been doing at Interact is keeping a meticulous spreadsheet that breaks down productions according to diversity. The data considers everything from works by women and transgender playwrights to how many actors of color were cast in lead roles.

“It tells us where we are with our own history,” Rozin said. “It tells us exactly where we are. We are trying to represent diversity and inclusion because it matters.”

In its 30th anniversary season, InterAct is producing two different plays by transgender playwrights, as well as "Human Rites," a play featuring an African-American actress in the lead role.

“People’s attitudes can sometimes take awhile to change,” Rozin said. “The short answer is just do it anyway.”

For InterAct, this has meant taking chances on more socio-politically driven shows that have helped to define the company’s reputation. In the last three decades, the stories have noticeably shifted to consider more international and LGBT voices, and welcomed more people of color onto the stage.

“I want to focus on racism and internalized white supremacy culture because it’s so present in our community right now.” – Amy Smith, co-director at Headlong Dance Theater in PointBreeze

In recent years, other companies, like the LGBT-driven Mauckingbird Theatre Company in Chestnut Hill, have helped to spotlight other less mainstream shows about queer artists and characters. And Beyond Orientalism, a discussion about the Asian-American experience on stage, has also inspired powerful questions about tokenism and stereotypes, while longtime black company Freedom Theater has been bringing important works written, directed and performed by black artists in North Philly.

Philly’s Fringe Arts has also helped nurture emerging voices that might otherwise be missing from the mainstream stages. Pig Iron’s most recent Fringe production, for example, featured an enormous cast ranging from kids to seniors, with a more noticeable racial diversity than has been seen in most of its prior productions.

Tom Reing, the founder and artistic director of Inis Nua Theatre Company in Center City, says that even though his company specializes in works from the United Kingdom, he’s interested in considering smart and thought-provoking multi-ethnic and racial storytelling. Example: This season’s “The Swallowing Dark,” a play written by a woman, told the story of Zimbabwe asylum seekers in Liverpool, England. Not only did the play address racial and cultural divides – it focused on immigration issues ripped from the headlines.

“The goal,” Reing said, “is to see something through a different cultural lens, though I definitely think the Philly theater community could be better.”

A few years ago Reing was involved in a production of Shakespeare’s “Richard II” at the Philadelphia Art Museum that featured a diverse cast he was especially proud of. “We wanted to reflect the community we live in,” he said, adding that for theater to ultimately be successful, it needs to consider many more black and brown, LGBT and women’s voices.

In its 30th anniversary season, the InterAct Theatre Company is producing “Human Rites,” a play featuring an African-American actress in the lead role, and two different plays by transgender playwrights.

Amy Smith, co-director at Headlong Dance Theater in Point Breeze, is challenging white people in the local arts community to make a concerted effort to be smarter and more inclusive when it comes to everything from selecting projects to casting them. Last month, Smith put out a call to action on Facebook in hopes of generating support for what she’s calling a White Anti-Racist Learning Group.

“I want to focus on racism and internalized white supremacy culture because it’s so present in our community right now,” she said. While still very much in its planning stages, she envisions the monthly meet-up as a learning group co-facilitated by Smith and two artists of color.

“I’ve spent the past few years educating myself about race equity and inclusion broadly, toward increasing my own knowledge base around these questions and creating healthier and more inclusive situations for staff and students at Headlong and the Headlong Performance Institute,” explained Smith. “This fall I did a facilitator training with Art Equity that helped me see even more clearly how I can participate in and agitate for the work that needs to be done in Philadelphia’s theater and dance communities.”

According to Smith, theater and dance companies have a lot of work to do toward racial inclusivity, starting with how companies even consider inclusivity. She encourages white artists to talk to people of color in the arts, to learn more about their experiences, and to spearhead projects that consider more unique voices.

Most times it comes down to what projects get the green light, “like actively seeking out to program or engaging works by artists of color, specifically beyond traditional acknowledgement times (i.e. Black History Month, Indigenous Heritage Month, etc.),” Smith said. “And learn more about the experiences of artists and arts leaders of color by having informational meetings with them.”

Another big push is on the administrative side. If more artistic directors were of color, said Smith, it would show in what gets produced. But there’s still a lot that can be done as leadership shifts and younger theater companies spring up to tell these stories.

“Predominantly white arts organizations in Philly should commit to continual professional development and education about race equity, anti-racism trainings, inclusive hiring and casting practices, and board development practices,” she said. “These require a commitment of time and money, as well as accountability measures.”

Terrell Green/Twitter

Terrell Green/Twitter Source/Theatre Philadelphia

Source/Theatre Philadelphia Photo courtesy/Leigh Goldenberg

Photo courtesy/Leigh Goldenberg Source/www.interacttheatre.org

Source/www.interacttheatre.org