September 29, 2023

Source/Fight for the Future

Source/Fight for the Future

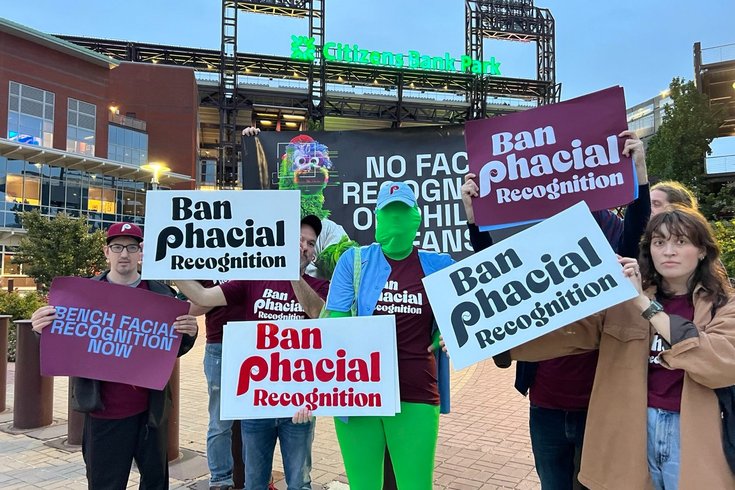

Protesters at Citizens Bank Park on Thursday voice their opposition to the Phillies' facial recognition entrance. The voluntary ticketing system is being tested by MLB and is only available in Philadelphia.

Demonstrators gathered outside Citizens Bank Park on Thursday night to protest the facial recognition technology that the Phillies and Major League Baseball debuted last month at the ballpark's first base gate. The opt-in ticketing system is being tested in Philadelphia as a way to speed up entry to games, but privacy advocates say the use of biometrics is a concerning trend that puts people's safety and data at risk.

Digital rights advocates showed up at the ballpark wearing T-shirts and and carrying signs that said "Ban Phacial Recognition." Some distributed flyers to fans using the Go-Ahead Entry gate, which uses the facial recognition technology.

"Introducing facial recognition at ballparks is a surefire way to ruin America's national pastime, or any outing to catch your favorite team," Caitlin Seeley George, a campaign director at digital rights organization Fight for the Future, said in a statement. "This is techno solutionism at its worst — we don't need to 'fix' our current system of paper or digital tickets because it isn't broken. And there is nothing convenient about giving your most sensitive personal information to a company that could sell it, share it, or leave it unsecure so it gets stolen."

Fans who want to use the new entry system must upload their selfies on the MLB Ballpark app, the league's ticketing platform. The app creates unique digital IDs linked to fans' biometric data, allowing them to pass through scanners at the designated gate instead of presenting electronic tickets to event staff.

The Phillies rolled out the technology in mid-August. By the end of the month, more than 7,000 fans reportedly had opted in.

Leaders from 11 rights organizations wrote a letter to MLB this week calling for the cancelation of the program, which may be expanded to other cities next year.

"Most facial recognition technology stores people's biometric data in massive databases, and no matter what tech companies say about the safety of that data, they cannot ensure its security," the letter said. "Hackers and identity thieves are constantly finding ways to breach even the most secure data storage systems. When it comes to face surveillance data, the consequences of a breach can't be overstated – unlike a credit card number, you can't replace your face if it's stolen."

Advocates say there are other dangers with facial recognition, including the possibility that it will be used for fan surveillance. At New York's Madison Square Garden, Knicks and Rangers owner James Dolan has used facial recognition to ban people from attending games and other events if they or their employers are involved in litigation against his businesses. Dolan's company was sued last December over the bans, and a number of artists signed a pledge against the use of facial recognition technology at venues.

The Phillies declined to comment on Thursday's protest, referring questions to MLB.

An MLB spokesperson reiterated Friday that the Phillies' Go-Ahead Entry gate is a voluntary option for fans who want to use it at their own discretion.

"No images are stored in the system and it is not being used for security monitoring," the spokesperson said. "This fully optional service is being offered solely to improve the fan experience for fans who choose to use it."

Privacy groups contend facial recognition puts people at risk of being falsely matched during criminal investigations. The groups that wrote to MLB cited a 2019 experiment by the American Civil Liberties Union, which tested the accuracy of one type of facial recognition software. With the aid of a computer scientist, the ACLU fed the software headshots of athletes on the Boston Red Sox, New England Patriots and other teams to see whether they would be matched with people in a database of 20,000 public arrest photos. About 1 in 6 of the pro athletes' pictures generated false matches.

In recent years, tech giants like IBM, Microsoft and Amazon have paused sales of their facial recognition software to police departments and other government agencies. IBM cited the potential for racial profiling and mass surveillance that could threaten free speech and violate human rights. Still, smaller companies dedicated to the development of facial recognition and other biometric tools have stepped in to provide their products to law enforcement agencies.

The Phillies told the Associated Press there is a distinction between facial authentication — the type of technology they're using — and other facial recognition systems.

"This is not scanning a crowd looking for people," Phillies vice president and chief technology officer Sean Walker said. "This is determining if a person is authenticated. We're not tied to any law enforcement. There's certainly no sharing of the data. It's simply to get you into the ballpark. It's not facial surveillance."

MLB did not immediately say which company is providing the technology used for Go-Ahead Entry.

For security at ballpark entrances, the Phillies and other MLB teams partner with Evolv Technology, a Massachusetts company that specializes in AI gun-detection software. At the Phillies' first base and left field gates, the company's scanners enable fans to go through security without opening bags, emptying pockets and being screened by staff with metal detectors.

Evolv's security systems and others like them have been installed by dozens of school districts across the U.S., with mixed results. On numerous occasions, The Intercept reported in May, Evolv's scanners either failed to detect weapons that were later used in crimes or they inaccurately flagged objects that were not security threats. Evolv and similar companies have faced growing scrutiny over claims that they've inflated the capabilities of their AI systems.

This week, New York prohibited using facial recognition in schools, joining a number of cities, counties and states that have passed laws either restricting or banning the technology. Federal lawmakers also have been weighing legislation to enact a wider moratorium on the use of facial recognition and other biometric technology.

The protesters at Citizens Bank Park and their allies say people attending sports games and other live events shouldn't be enticed to share sensitive personal data to efficiently enter venues.

"There is no place for violating civil and human rights in sports, which at their best bring fans of different backgrounds together and unites them," said Michael De Dora, U.S. policy and advocacy manager at Access Now. "All professional sports leagues must ensure those who enter their stadiums are free from harmful surveillance."