June 30, 2016

Matawan Historical Society/Facebook

Matawan Historical Society/Facebook

In the summer of 1916, four were killed by sharks in New Jersey, and our modern fear of man-eating fish was born.

Before you spend the entire holiday weekend under a beach umbrella, scared you'll get eaten by a shark, know this: From 2006-2010, there was an average of 4.2 fatal shark attacks across the globe, according to the nonprofit organization Oceana. Even last year, when the number of attacks was higher than normal, only one in the United States resulted in a fatality, and no attacks occurred off the Jersey Shore (one happened in New York, the rest down South). It's a "statistically irrational" thing to be worried about, as one researcher put it.

Yet those statistics didn't exist 100 years ago, mainly because there was no given reason to fear sharks. That all changed on a July day down the shore.

In the summer of 1916, the modern fear of sharks as human predators was born. Four people were killed in attacks in New Jersey during a summer that prompted national discussion and even a response from the White House. Its effects still linger today.

At the time, many Americans had either never seen a shark or didn't even believe they existed. Then, on July 1, 1916, 25-year-old Charles Vansant was swimming in shallow water off the coast of Beach Haven when he was snatched by the jaws of a shark.

A lifeguard pulled in Vansant, and he bled to death on the beach. Five days later, Charles Bruder, 27, a bellhop at a Spring Lake hotel, was attacked and killed while swimming in the ocean. Panic was followed by confusion. Per National Geographic:

Some suggested it was a massive sea turtle, or a school of sea turtles that snapped at Bruder and Vansant, says George Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research and curator for the International Shark Attack file.

Scientists had a loose grasp on shark behavior.

“There were all kinds of misconceptions,” Burgess says. “At least one school of thought at the time was this was all stuff of rumors and fabrications.”

Not only were scientists dumbfounded, but the public was (understandably) freaking out, and the media's coverage of the first two attacks fanned the flames of fear. Imagine going from being barely aware of the very existence of sharks, to reading this in The New York Times about the Spring Lake attack:

As the life guards drew near him the water about the man was suddenly tinged with red and he shrieked loudly. A woman on shore cried that the man in the red canoe had upset, but others realized it was blood that colored the water and women fainted at the sight. As the life guards reached for the swimmer he cried out that a shark had bitten him and then fainted.

The most bizarre attack would occur a week after Bruder's death; this time, the shark would strike inland, not out in the ocean.

The culprit of the third attack became known as the Matawan Man-eater. On July 12, along the Matawan Creek, a group of factory workers and the young boys helping them took a break to go swimming. Per WNYC:

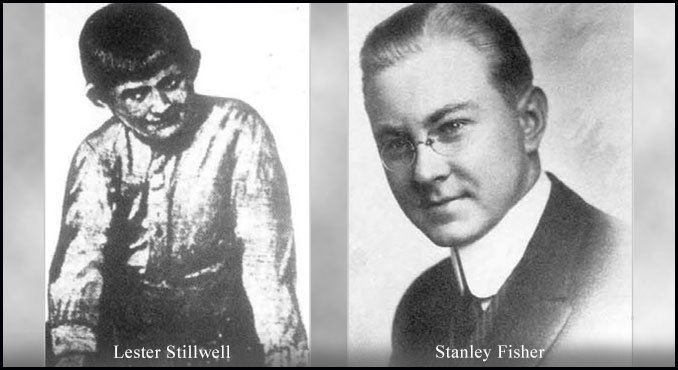

Among them was 11-year-old Lester Stillwell, a frail epileptic from the poor side of town. His friends later recounted that Lester was floating on his back when what seemed like a shadow rose from below, struck Lester with tremendous force and lifted him out of the water, before taking him under.

Among the first to arrive on the scene was the 24-year-old son of a sea captain named Stanley Fisher. He and some other young men stood in rowboats and used poles to probe the murky water for Lester. After a while, it became clear to the men — and to the townsfolk crowding the creek bank — that they were no longer trying to save Lester's life. They were searching for his body.

Fisher would become the second victim of the Man-eater and the fourth of the summer, as he was mauled to death trying to recover the boy's body. Arthur Smith, who was in the rescue team wading in the creek, was nearly ensnared in the shark's jaws but got into the boat before being dragged down. He did, however, sustain a cut that required 14 stitches.

Lester Stillwell and Stanley Fisher were both killed by a shark in the Matawan Creek during the summer of 1916.

A white shark was eventually caught nearby, and newspapers reported at the time that inside were body parts from Fisher and Stillwell, although none of that is confirmed by official records, only media reports.

A century later, Matawan has struggled with exactly how to honor two people violently killed by a shark. A new granite memorial to the two is being unveiled this summer at Memorial Park in the center of town, according to NJ.com. Additionally, a nine-day event in July is being held by the local chamber of commerce to commemorate the centennial anniversary.

Stopped by Rose Hill cemetary in Matawan to pay respect to those who lost their lives to the shark in 1916. pic.twitter.com/J0s1peUUXj

— Mr. Smith (@SmithUSHistory) May 19, 2016

Though the Matawan Historical Society notes that the Jersey Shore attacks are widely believed to be the inspiration for the novel that inspired "Jaws," the author has denied that claim.

One thing's for sure: "Jaws" was a work of fiction, but the summer of 1916 was real and was the beginning of our modern understanding — and fear — of sharks.

Matawan Historical Society/Source

Matawan Historical Society/Source