March 07, 2018

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoice

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoice

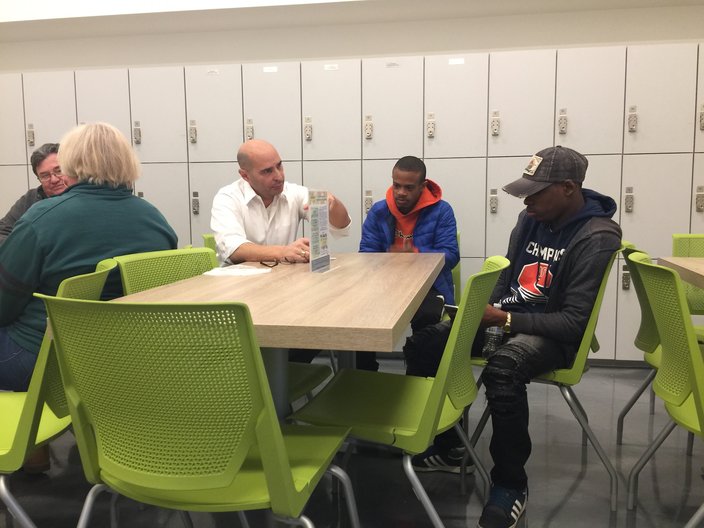

An eclectic group joined Common Pleas Court Judge Scott DiClaudio and several defendants performing community service at MANNA on Monday, March 5, 2018.

On Monday evening, a unique collection of people gathered around food-prep tables inside a non-profit organization's kitchen in Spring Garden.

There was a common-pleas court judge and several law clerks. An assistant district attorney and a pair of public defenders, one retired. And four volunteers who heard about the gathering just because they'd been in that judge's courtroom at some point in recent months.

They were not alone.

A table over from a separate group of volunteers hard at work cutting up hundreds of pounds of potatoes was a chef from the Metropolitan Area Neighborhood Nutrition Alliance (MANNA), an organization which provides people facing life-threatening illnesses with food and nutrition counseling.

And there were nine other folks drawn there – not necessarily on a mission of volunteerism. At least not at first.

They were there because Scott DiClaudio, the judge who donned an apron but not a hair net since he's follicularly challenged, made them an offer they were loath to refuse.

The men – they ranged in age from 21 to 49 – faced charges before DiClaudio of varying degrees. Drug offenses. Burglary. Aggravated assault and terroristic threats.

When they sought a plea deal, DiClaudio invited them to work off some of their community-service hours not for, but alongside, him.

They accepted an offer made to a select few defendants who showed promise of shifting their direction in life. And, with that, Monday marked the third time that the defense attorney-turned-judge who's faced some harsh news coverage over the years bonded with people convicted in his court to help the needy.

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoice

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoiceBefore they got to work in MANNA's kitchen, Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Scott DiClaudio talked about job prospects with a pair of men on hand to perform community service.

It's an unusual scenario to say the least. If one of his peers is doing the same thing with men and women they have sentenced, then DiClaudio, who presides over cases from Northeast Philadelphia, the East Division and Center City, said he's unaware of it.

But that didn't stop the crew from chopping onions or scooping crab filling into flounder filets for roughly two hours on Monday.

No, the time dedicated to MANNA doesn't go a long way toward fulfilling the terms of sentencing, but that mattered little to those who found a unique brand of togetherness in the place where their life choices brought them.

"I have some good news and some bad news: There's a lot of work to do," the judge told the group in MANNA's lobby before they watched a video about the non-profit's mission.

Before long, they headed into the kitchen along North 20th Street not too far from the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

"We'll do some good things here today," the judge said.

Before they got to work, small talk was made. Terry Higgins, a retiree who sometimes sits in DiClaudio's courtroom just to watch the goings-on, quipped that he told the judge "it's either going to an AA meeting, church or sitting in his courtroom."

A young defendant spoke of the challenges getting a job – DiClaudio said he'd talk to the man's probation officer – and how he hadn't seen his mother in years, but she's coming up from the Washington, D.C. area this weekend for a visit.

They spoke about what kind of jobs they'd like to have one day. Among the responses: firefighter, arborist and chef.

And then they got to work.

If any of the defendants were solely motivated by a need to work off community service hours, they gave zero indication, particularly after that video explained the food would go to those in poor health and dire need. MANNA delivers 21 meals to doorsteps each week.

"I can't give out recipes now!" joked MANNA executive chef Keith Lucas as his volunteers settled in at the prep tables near Freezer No. 6. He spoke about the nonprofit's reliance on a constant stream of volunteers who help them achieve goals.

On this day alone, groups from Drexel University, the Interfaith Center and Alpha Sigma Rho were on the schedule.

The week-ahead schedule taped to the wall listed visits from teenagers from NextSteps AmeriCorps, Roxborough High School's Breakfast Club, Hill-Friedman World Academy, Mastery Shoemaker and Lenfest along with college-aged volunteers from East Tennessee State and Michigan State universities. That was about half of the week's volunteer roster.

"We have groups like this all day, every day. It helps us out a lot," said Lucas, a former fine-dining chef who's been with MANNA for 20 years. "(We provide) 21 meals a week with supplements and desserts for 1,050 clients. The cause made me stay as long as I have."

There would be 950 of the stuffed flounder meals prepped and then frozen for deliveries that started Tuesday. Two hundred pounds of potatoes would be cut. Pepper steak was on the list for the next day's effort.

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoice

Brian Hickey/PhillyVoiceWhile preparing stuffed flounder, Judge Scott DiClaudio and several men on probation talked about the nuances of how a guilty plea impacted their lives.

Judge DiClaudio made his way around the room connecting with the volunteers.

As a trio of probationers used dippers to get the crab mix into the filets, one spoke about unexpectedly learning last month that he'd lost his driver's license as part of his plea deal. That's not only made it difficult for him to keep a job, but get his daughter to school.

This doesn't seem like a good proposition for someone who got three years of probation stemming from a guilty plea on drug possession with intent to distribute charges.

"People think their life is bad, but sometimes, you don't know just how blessed you are." –Andre Richard

"I don't think that's fair at all," said 21-year-old Jalil Holder of the Lower Northeast. "They should've told me that at first. Now I have a car that I can't drive."

"Taking away your license, in my humble opinion, does no good, especially on a first offense," DiClaudio commiserated. "Stay in touch. We should go to Harrisburg to convince someone to help us change that."

Andre Richard, a 26-year-old from Kensington, had been to MANNA, albeit under different circumstances, in the past.

Facing a year of probation because of drug offense and "making bad decisions," he appreciated the chance to return. That this will only go a small way toward completing the 100 hours of community service he owes mattered little.

"This helps people, and seeing that video made it real for me, seeing those patients who will get the food we're preparing," he said during a break in Monday night's action. "People think their life is bad, but sometimes, you don't know just how blessed you are. These people are living to think about whether they'll have a next day.

"Coming here just made sense to me. This is all about helping people in need and giving back."

What was most unique about these two hours was the chance that it gave an eclectic group to get together in a setting that wasn't a courthouse.

The one-time defendants were afforded a chance to speak with those on the bench, and with law degrees, about who they really were. Veils were pulled back and predisposed notions cast aside.

For DiClaudio, who said negative coverage in his own past has nothing to do with his present and future endeavors, that was a great thing.

While the offer to volunteer is open to anyone who is interested, he said he's primarily focused on younger defendants.

He usually announces the option during his first couple cases of a given day. He checks back in with some volunteers via status hearings but, ideally, doesn't need to cross paths with them again as they've steered clear of the legal system.

"A lot of negotiations in my courtroom involve community service, which I've done a lot of when I was in private practice," he said. "It comes down to this: I want to practice what I preach. If I'm obligating them to give back, the least I can do is participate myself. It's a great opportunity to help those in need."