May 17, 2019

Reading Tom/via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

Reading Tom/via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

Mile End Hospital is a National Health Service community hospital in the Stepney part of East London. In a British-style system, the government fully owns, operates and staffs all health care facilities.

The role of government in the U.S. health care system has been contentious long before the recent emergence of Medicare-For-All proposals among Democratic presidential candidates. Advocates of so-called free-market health care have long described government intervention as “un-American” and “socialist.” Their arguments can perhaps be best summarize in the phrase let’s “get government out and let markets work in health care.”

Yet a closer look at the development of the U.S. health care system paints a starkly different picture. Indeed, publicly owned hospitals – that is, hospitals run by local, state, and federal governments – have played an important and substantive role throughout the country’s history. Government has always been extensively involved in the provision of health care in one form or another.

And to the surprise of many today, events could have taken a very different turn. The U.S. could potentially even have ended up with a British-style, government-run health care system. Yet, the country went a different route. Instead of expanding, public hospitals have been closing since the 1960s in large numbers. How come?

In my recent academic paper on the subject, I analyzed the creation and closure of public hospitals in California, the state with one of the most extensive public hospitals system in the nation. My findings indicate that when state and federal governments extended health coverage through programs like Medicaid and Medicare, all but the most well-resourced local governments in turn began closing their hospitals.

My findings bear implications for policy debates today. Advocates for any large-scale health reform effort such as Medicare-For-All should be mindful of the eventual unintended side-effects they may trigger.

There are many different types of health systems depending on the extent and type of government involvement.

In a British-style system, government fully owns, operates, and staffs all health care facilities. Because government provides both funding and services, this system can rightfully be described as socialist.

At the other end of the spectrum is a health care system where government fully stays on the sidelines. That is, government provides neither funding nor services. Individuals are thus left to fend for themselves, no matter their health or financial status. Given the ubiquity of government today, a more realistic derivative of this system involves government taking on a certain amount of regulatory function.

The current system in the United States is somewhat of an amalgam of both extremes and everything in between. The Veterans Affairs and other government-run hospitals serve as a bookend on one end, and the individual market where consumers choose health care plans offered by private companies as one on the other.

Yet in the context of the U.S. system, it is important to note that public hospitals have played a role in this system since colonial times. For example, two of country’s most famous hospitals, Philadelphia General Hospital and New York’s Bellevue Hospital, were founded in the 1730s. Even today, public hospitals, run by both state and local governments, serve millions of Americans.

At the same time, federal and state governments have become significantly involved in the health care field. However, most of this involvement revolves around shouldering extensive funding obligations. And virtually all Americans benefits from this involvement in the form of Medicaid, Medicare, and tax deductions for employer-sponsored health insurance. However, only rarely does government directly take on the provision of services.

Notably, while policy details remain vague, Medicare-For-All would likely expand this role by eliminating any non-governmental payer while maintaining the private provision of services.

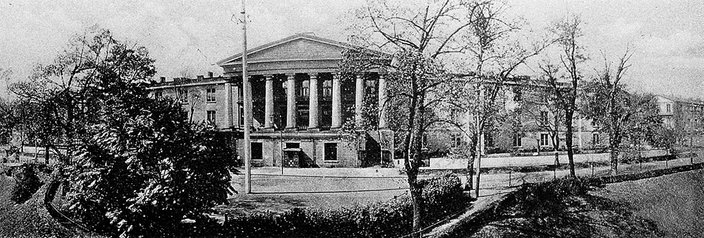

The exterior of Philadelphia General Hospital, which was founded in the 1730s. A public hospital in West Philadelphia, it was one of the country's most famous hospitals. It closed in 1977.

In their earliest days, public hospitals served as little more than holding areas for the poor. Yet over time, they have contributed tremendously to the improvement of the health of the nation.

These contributions ranged from providing services to the blind, the deaf, the disabled, the aged, and the mentally ill, to containing contagious diseases and epidemics, such as smallpox, tuberculosis, typhoid, leprosy, and venereal diseases.

But then, starting in the 1960s, more and more public hospitals began to close their doors for good. What happened?

As I show in my recent paper, a major contributor to these closures were expansions of public health coverage programs beginning with the New Deal, and culminating in Medicaid and Medicare. The programs removed the onus from local governments to provide for the needy and sick by shifting the responsibility to state and federal governments. Providing care for the poor was no longer a housekeeping function of local governments. Government shifted from a role of locally producing services to one solely financing them.

After all, the “deserving poor” could always get coverage through the new and growing joint state-federal programs.

Developments in California, the state with the most elaborate system of local hospitals by the 1960s, are emblematic for the nation. While the state’s network of county hospitals reached near-universal coverage into the early 1960s, only a dozen or so hospitals remain open today, including Zuckerberg General in San Francisco and Harbor/UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Ultimately, only well-resourced local governments were able to keep their doors open, and the state’s poorest communities where left out.

Undoing the nation’s safety net of public hospitals has had crucial implications for the nation’s health.

For one, there are direct implications for the broader health care systems. Public hospitals have disproportionately shouldered key roles that private providers often loathe to take on. These include trauma and burn care, provider education, and access for minorities and populations that are hard to serve like those with HIV or substance abuse problems.

Moreover, throughout this nation’s history, public hospitals have served as a backstop for the poorest members of society. With continued closures, access for the most destitute becomes even more challenging.

While some members of society have gained access to public health coverage, it is important to remember than many have been left out. Indeed, eligibility guidelines for programs like Medicaid continue to excluded most childless adults in many states, no matter how poor. Of course, immigrants both documented and undocumented, are also generally excluded from these programs. Individuals losing coverage for failure to comply with Medicaid work requirements are just the newest members on this list. Any Medicare-For-All proposal is unlikely to address all of these shortcomings.

It is also important to remember that replacing local institutions like public hospitals with federal and state programs introduced significant vagaries into the safety net. While a public hospital’s doors are always open, it is relatively simple for Congress and the President to alter eligibility for programs like Medicaid. Medicare-For-All coverage today thus can turn quickly into lack of insurance tomorrow.

Crucially, these developments have also taken questions of health care access off local agendas. With the discussion shifted to the state and federal level, caring for our neighbors has become a more distant concern to be handled down at the state or national capital. Unquestionably, one may be more hesitant cutting access for someone down the street than for some faceless person across the country.

Going forward, all health care reforms including Medicare-For-All should be mindful of potential side effects. Importantly, they should pay attention to the crucial role public hospitals have played in this nation, and ponder the implication of their ongoing demise.![]()

Simon F. Haeder, Assistant Professor of Political Science, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Credit/The Wellcome Collection via Wikimedia CC-BY-4.0

Credit/The Wellcome Collection via Wikimedia CC-BY-4.0