January 17, 2023

Source/The New York Public Library

Source/The New York Public Library

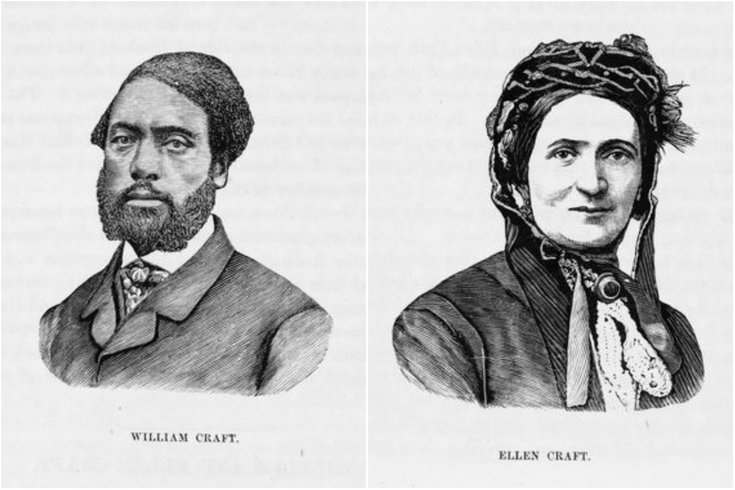

William and Ellen Craft, seen above in 1872 illustrations, escaped slavery through trains from Macon, Georgia to Philadelphia. Ellen disguised herself as a white man and William posed as her slave.

On the morning of Dec. 20, 1848, William and Ellen Craft began their roughly 1,000-mile journey to freedom. The enslaved couple had planned an elaborate escape from Macon, Georgia, one that hinged on a gutsy gambit: that Ellen could pass as a rich, sickly white man and William as her slave.

Slowly, carefully, the Crafts had assembled the disguise: a white shirt, an ill-fitting vest, a baggy coat, pants sewn by Ellen herself, a pair of thick-soled boots to give her an extra inch of height, green-tinted glasses and a silky black cravat to signify wealth. Ellen donned it all before exiting their shared cottage in the pre-dawn hours. When she arrived at the train station later that day, she bought train tickets for herself and William in broad daylight, tickets that would take them all the way to the free city of Philadelphia. No one stopped her.

The couple's odyssey is chronicled in a new book by Ilyon Woo, "Master Slave Husband Wife," published Tuesday by Simon & Schuster. Woo will appear at the Parkway Central Library on Thursday to discuss the astonishing saga.

"I think this story (has) maybe been a difficult one for us as a nation to remember because it doesn't give us any kind of easy closure," Woo said. "It's a story in which all of America was very much implicated, and people in the North had to make a choice as well as people in the South. And I think the fact that there's no easy ending that lets everybody off the hook makes it a story that's been difficult for us to reckon with nationally."

Though many slaves made headlines in the antebellum era for daring escapes — most notably, William "Box" Brown, who mailed himself in a wooden crate to Philly abolitionists — only the Crafts could have pulled off this particular getaway. Their plan played to each of their strengths, and some dark family history.

William and Ellen were owned by different masters, but they were both skilled, urban slaves. William, a longtime apprentice to a Macon cabinetmaker, had made an arrangement with his owner, Ira Hamilton Taylor, that allowed him to pocket a small fraction of wages earned from jobs in town. The rest, of course, went back to Taylor. Ellen, meanwhile, was a talented seamstress, owned by her half-sister, Eliza Collins. Before that, their father, James Smith, had been Ellen's master. He still owned Ellen's mother, Maria, whom he had raped when she was a teenager.

This uncomfortable reality of slavery meant Ellen was extremely light-skinned, and often mistaken for a white woman. But traveling as a white woman with a male slave would raise eyebrows, so she posed instead as a man, one afflicted by rheumatism. This way, no one would question the bandages on her face, an extra layer of disguise that concealed her hairless cheeks, or the sling supporting her arm, which got her out of signing at hotels or stations, since she was illiterate and couldn't sign her name. Best of all, as the Crafts correctly assumed, conductors and other passengers were less inclined to bother a sickly gentleman onboard with pleasantries or difficult questions.

Four days and three trains later, the Crafts arrived in Philadelphia. Riding in the carriage to a boarding house that Christmas Eve, Ellen "wept like a child," praising God for their safe passage, according to the Crafts' memoir "Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom." But they didn't stay in town long. The couple continued north to Boston in January, warned by local abolitionists that were vulnerable in Philadelphia.

"That's one thing I found really surprising in my research, because you do associate Philadelphia with (Independence) Hall and the birthplace of American freedom," Woo said. "Yet it wasn't considered safe for liberty seekers like the Crafts."

Philadelphia had the largest free Black population in the North in 1848, but the city's proximity to the South meant it was "the main place for people to both kidnap and seek out self-emancipated people," Woo said. These contradictions were embodied in pockets of the city like Carolina Row, a section of Spruce Street occupied by wealthy sons of the South who had come to study, or put down roots.

The local Vigilance Committee and Female Vigilant Association, clandestine networks of activists, had once assisted fugitive slaves, but were "under duress" in 1848, Woo explained. Mobs recently had targeted anti-slavery societies, burning down their meeting places, like Pennsylvania Hall, and attacking abolitionists with bricks and stones. A recent influx of immigrants also had ignited nativism in Philadelphia, and the "Black population was targeted for repeated, violent assault," Woo wrote. When Robert Purvis, a free Black man and president of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, fled in 1842, relocating his family to a Quaker community in what is now Northeast Philly, the Vigilance Committee virtually vanished.

The Crafts spent the next year and a half in New England, traveling to different towns as featured speakers at abolitionist meetings, sharing their story to galvanize support for the cause. But the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act forced them to flee yet again, as it empowered slave catchers like never before. Though Boston's abolitionist community was much stronger than Philadelphia's, harassing the catchers who came for the Crafts so relentlessly that they left the city, William and Ellen were ready to start a family, and they had vowed at the start of their journey to never let their children experience what they had.

And so they made a home in London for nearly 20 years, raising five children (a sixth died in infancy), before returning to an emancipated, post-Civil War America. Those children and their descendants continued their parents' work as activists in their own right. One of them, the Crafts' great-great-granddaughter Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely, was a Freedom Rider in the 1960s, "reversing" her ancestors' journey by traveling from her hometown of Harlem to Southern sites of protest — or as she called them "the belly of the beast."

"I ended up working less than a hundred miles from where they escaped," Preacely said. "And it was a profound experience. Every day, I felt the weight, the blood, the pride, the fear, all of those things of my ancestors as I was walking those roads, knocking on doors, getting arrested, getting jailed for protest activities and voter registration."

Preacely had known about William and Ellen since she was a child, but additional scholarship in her lifetime has filled in some of the gaps, and corrected some strategic lies the Crafts told in their day. For instance, on the lecture circuit, Ellen claimed her master was dead, to obscure their identity and shield them from slave catchers. William also claimed at various points that he had to talk timid Ellen into the disguise, and he is listed as the sole author of "Running a Thousand Miles to Freedom," even though the couple wrote it together. Both revisions were designed to conform to Victorian concepts of femininity — a time when women's voices were also suppressed, Preacely noted.

"When people read [this] book, they're going to be informed more than just about what my great-great-grandparents did, but what was going on contiguous to their lives," she continued. "So that we can see how Black lives were manipulated, and the role of history has been manipulated. Because when I was in school in the '40s, we didn't have a lot of (Black) people in our books, or our teachers knowing how many Blacks rebelled.

"People didn't want to know the truth."

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt | @thePhillyVoice Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice Have a news tip? Let us know.