March 15, 2021

Jules A./Pixabay

Jules A./Pixabay

When more than one high-powered magnet is swallowed, they can attract each other across body tissue, causing obstructions to the blood supply, tissue necrosis, sepsis and death.

High-powered magnet sets marketed as stress toys, educational tools and desk toys are among the most dangerous ingestion hazards in children.

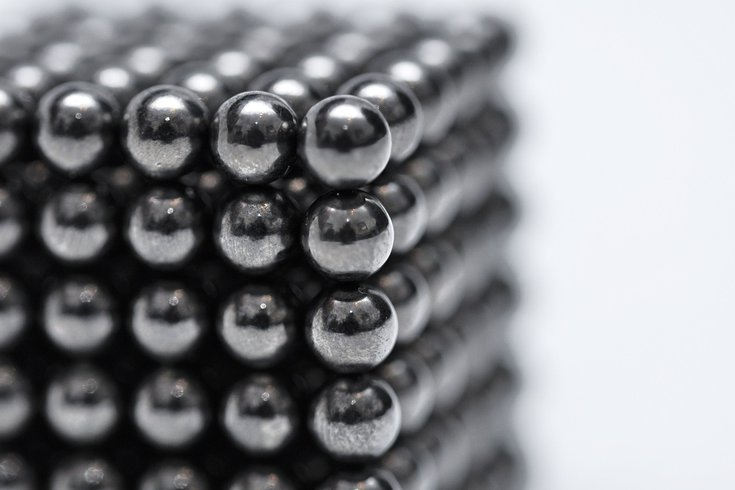

Marketed under names like Zen Magnets, DigiDots and Buckyballs, these small, shiny magnets made from rare earth metals, including neodymium, are sold in sets of up to 200 ball or cube-like pieces that can be contorted into different shapes.

These magnets have caused thousands of injuries, especially among young children. A new study found U.S. poison centers received 5,738 calls relating to the ingestion of these products between 2008 and 2019, with cases surging after a two-year ban on their sale was lifted about four years ago.

The magnets not only serve as a choking hazard, but when more than one are swallowed, they can attract each other across body tissue, causing obstructions to the blood supply, tissue necrosis, sepsis and death.

An emergency endoscopy or abdominal surgery is usually needed to remove them. Two doctors raised concerns in 2019, telling STAT that they had removed 54 tiny toy magnets from the digestive systems of four children over the course of several weeks.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission had halted the sale of high-powered magnet sets in 2012 and issued a recall. Two years later the agency issued a ruling that effectively eliminated the sale of these magnets. But it was overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals in December 2016.

The study, published in the Journal of Pediatrics, found that the average number of magnet-related cases per year decreased 33% from 2012 to 2017, but once the ban was lifted, the average increased by 444%. The researchers also found a 355% increase in the number of cases that were serious enough to require hospital treatment.

Cases from 2018 and 2019 alone accounted for 39% of magnet cases since 2008, the researchers said.

"Regulations on these products were effective, and the dramatic increase in the number of high-powered magnet related injuries since the ban was lifted — even compared to pre-ban numbers — is alarming," said lead author Dr. Leah Middleberg, an emergency medicine physician at Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"Patients don't always know if their child swallowed something or what they swallowed — they just know their child is uncomfortable — so when children are brought in, an exam and sometimes X-rays are needed to determine what's happening. Because damage caused by magnets can be serious, it's so important to keep these kinds of magnets out of reach of children, and ideally out of the home."

A majority of calls were for male children younger than 6 years of age. Almost half of the patients were treated at a hospital or health care facility, with older children more likely to be admitted to hospitals.

"While many cases occur among young children, parents need to be aware that high-powered magnets are a risk for teenagers as well," added Dr. Bryan Rudolph, co-senior author of the study and a gastroenterologist at Children's Hospital at Montefiore in The Bronx.

"Serious injuries can happen when teens use these products to mimic tongue or lip piercings. If there are children or teens who live in or frequently visit your home, don't buy these products. If you have high-powered magnets in your home, throw them away. The risk of serious injury is too great."

The founders of Zen Magnets and Buckyballs have since co-founded a new company, Speks, that markets the magnet sets to people who are 14 years or older. The product packaging contains warnings about the dangers of accidental ingestion

Rudolph and Middleberg support the need for preventive efforts and government action, including federal legislation that would limit the strength and size of magnets sold as sets. They also support reinstating the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission standard restricting the sale of high-powered magnets.

Parents who suspect a child has swallowed a high-powered magnet are urged to take the child to an emergency department for an X-ray immediately.