September 08, 2015

Kevin C. Shelly/PhillyVoice

Kevin C. Shelly/PhillyVoice

Andres Camacho III was gunned down nine years ago after walking away from this corner bodega at 35 Marlton Pike in the East Camden neighborhood of the city, not far from where he grew up and lived. A year-old county-wide cold case squad has re-released a video of a suspect and there is now a reward.

Unsolved homicides “are a stain on a family,” and “hurt so deep,” says veteran homicide investigator Marty Devlin.

Which means a big stain hangs over Camden, a fact understood by Devlin and the other members of a year-old cold case squad with a profound, deep and deadly seriousness.

The city of a little more than 77,000 residents had 152 unsolved murders in just the past five years.

The solve rates for slayings in Camden range from just 19 percent so far this year to 54 percent back in 2010.

By contrast, Philadelphia has had a solve rate of as high as the 71st percentile in recent years and as low as 58.5 percent. The national average for homicides in 2013 was 64 percent.

But for Andres Camacho Jr., cold cases aren’t about numbers or statistics: They are about his dead son and namesake, Andres Camacho III, or “Andy” to the family.

Andy’s children, now 17 and 14, ask their grandfather about the father who died half their lifetime ago as they struggle to remember.

That’s “when the tears come down,” says the elder Camacho, his words catching.

“They ask questions that I can’t explain,” he softly adds, admitting he had to take angina pain pills when he first learned of the murder.

“You want to die in a way. You are not the same for six months. Your life changes,” says the still grieving grandfather.

“It doesn’t go away, God knows. For any parent, it is the hardest thing in the world,” adds Camacho.

Solving the case, adding a measure of closure, won’t heal his aching heart.

But he hopes someone will come forward, identify a suspect in a re-released video, claim a recently-posted $1,000 reward, and help clear the case.

The younger Camacho was gunned down June 9, 2006, at about 9:45 p.m.

The day was a Friday. The 26-year-old Camden County parks worker had cashed a paycheck earlier in the day. He was still carrying the money still when he was shot – a possible reason for the shooting.

But there is another motive: Revenge.

Police believe Camacho was along about an hour earlier when a buddy robbed participants in an illegal dice game, potentially making the younger Camacho a target.

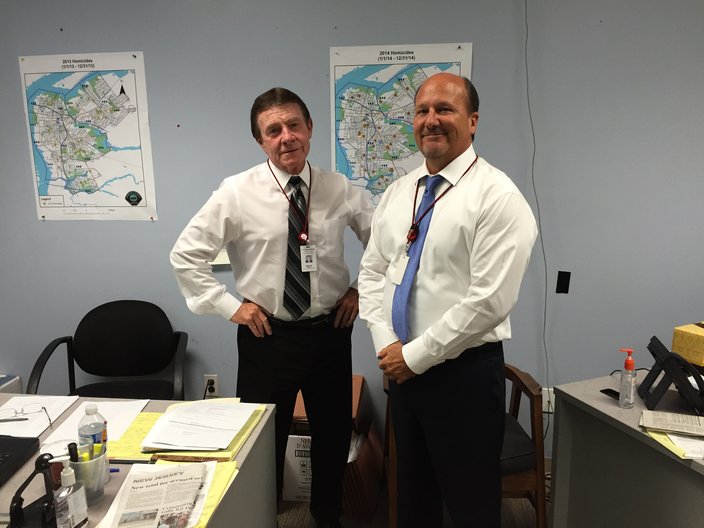

Investigators Marty Devlin and Joe Forte came out of retirement about a year ago to help form a cold case squad overseen by the Camden County Police Department with support from the county prosecutor's office. They are now focused on a nine-year-old unsolved fatal shooting of Andy Camacho. A $1,000 reward is offered and a video showing the victim and his suspected shooter has been rereleased. (Source: Camden County Police Department)

“But he was a human being. He had a family. He didn’t deserve to be shot down like a dog,” even if Camacho participated in the robbery during the craps game, says Devlin, a hard-boiled detective known to break down and cry while talking about a crime victim.

But Devlin – now 71 and a “consultant,” rather than a sworn officer – says that might explain why the younger Camacho was followed and shot repeatedly.

“Money and revenge” are the reasons behind most murders, adds Devlin, a veteran of the Philadelphia Police Department homicide squad and retired Camden County Prosecutor’s Office detective who helped crack the case of Fred Neulander, the rabbi who wanted to be free to pursue an affair and had his wife killed by hitmen.

The elder Camacho has heard about the dice game stickup theory, and while he doesn’t dispute that his son may have been involved, he too says, “No one deserves to be murdered.”

And more especially, no one deserves to be murdered without redress, a case gone cold, put in storage, collecting dust, largely forgotten.

“There’s really no justice,” in solving a cold case, says Devlin. “But there’s satisfaction.”

A satisfaction the squad would like to provide for the elder Camacho.

Peter Longo, a veteran narcotics detective from the prosecutor’s office assigned to the squad, says in a nine-square-mile town where everyone knows each other or each other’s family, there is less incentive for a Camden citizen to risk coming forward and cooperating.

“If we had cooperation, we’d solve 99 percent of all homicides,” agrees Devlin of the “no-snitch” culture that affects most urban areas.

Calling a case “cold” is partially a function of how old a case is, but it is more about if there are still active leads – or not.

In the Camacho case, the case is both old and cold despite a video showing Camacho leaving the store, being followed by a suspected shooter, getting gunned down just out of sight seconds later, with others ducking back into the shelter of the store, and then the suspect once again walking back into the video frame.

Joe Forte, the dry wit on the cold case squad – he describes himself as “Marty’s caddy” even though he was Devlin’s supervisor when they were with the prosecutor’s office – says reviving a cold case begins as “fresh eyes.”

“Sometimes that broadens it. Sometimes it narrows it. The original detective may have concentrated on a street rumor,” that didn’t prove out, says Forte.

Eyes are important to Devlin. Before he reads a case file, he reviews every picture, often more than once.

“I’m trying to be the eyes of the detective, to see what they saw,” when the case broke, he explains.

Longo said the next avenue is generally “going back and beating up the street,” returning to the scene, questioning witnesses.

Talking to the original officers, even if they have retired or moved, also helps, both say.

Despite TV dramas that show cases being solved in an hour via gizmos and lab science, what solves most cases – even when there is good video, as in the Camacho case – is a witness identification.

“It gets personal when you can’t find a witness to tell you what happened,” says Longo.

He shakes his head in frustration about the Camacho video.

“Look at the way the guy approached the victim. He walked right past an area where he knew there was a video camera and there are lights. And then he walks right back."

“Nothing happens in a vacuum. Somebody out there knows something,” says Longo.

“Anyone who has information, call authorities,” pleads Andy’s father.

• • •

HAVE INFORMATION?

If you have information about the Andy Camacho murder, please contact one of the detectives below:

Camden County Prosecutor’s Office Detective Pete Longo – (856) 580-5854

Camden County Police Department Detective Shawn Donlon – (856) 655-1334

Tips may also be emailed to ccpotips@ccprosecutor.org.