April 26, 2017

Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission/The Mystery of the Monongahela Indians

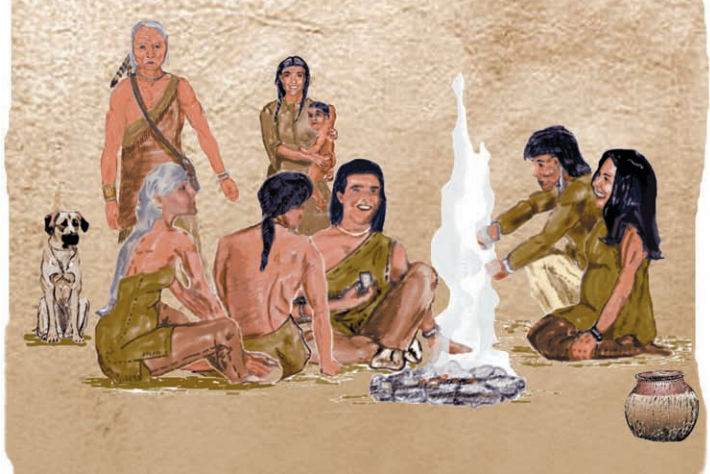

Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission/The Mystery of the Monongahela Indians

This artist's rendering of the Monongahela Native Americans is included in a state pamphlet on the mystery of what happened to the people.

For six centuries, a native people lived in the region that is now southwestern Pennsylvania.

Then they vanished without a trace.

"We have no idea what happens to them," John Nass, director of the California University of Pennsylvania's anthropology program, told PhillyVoice. "They basically vacate this part of the state, but we don’t know where they relocate to."

Nass and his undergraduate archeology students are studying the history of the Monongahela people, who occupied parts of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio and Maryland from about 1050 A.D. into the 1630s.

Attention to their work picked up recently with a local interest piece in the hometown Herald-Standard newspaper, which was followed by a feature from the Associated Press.

California University, however, has been working on sites in seven Pennsylvania counties where Monongahela artifacts have been found since 1969.

Experts knew of the Monongahela people as far back as the 1800s, but they weren't given their name, which comes from the Monongahela River, until the 1930s.

They survived as farmers who grew corn, beans and squash. They lived in villages that surrounded giant, vacant spaces — an equivalent of the modern town square — where they gathered and buried their dead.

What's unique about the Monongahela people is that, unlike other Native American groups, it isn't known what happened to them after Europeans began flooding the continent. The establishment of European trading routes in the region roughly lines up with the last documented timestamp of the Monongahela people.

Pictured are beads, a bone awl, and the blank for making fishing hooks used by the Monongahela people and discovered by researchers at the California University of Pennsylvania.

Trying to find clues to where they went has been tricky. Normally, for example, pottery with markings unique to a certain group of people may turn up somewhere else, indicating the path of migration.

The problem? Frankly, their pottery is pretty bad, and therefore not very distinguishable, according to California's biological anthropologist Dr. Cassandra Kuba, who's studying the people's health and diet.

"They're not sexy," Kuba said of their pottery. "You see one of their pieces of pottery at a museum and people go, 'What is that?'"

While their pottery was too boring to be helpful, Nass and Kuba had been able to piece together other pieces of evidence and get closer to where the Monongahela people ended up.

For example, Nass says, bowls didn't show up in their villages until the 1400s, indicating some sort of cultural shift — possibly an invitation to other tribes to come eat with them.

"Bowls you can use to feed people you want to be friends with," Nass said.One theory is the Monongahela people joined a neighboring tribe to avoid increasing territorial competition.

This bowl was used by the Monongahela people and discovered by researchers at the California University of Pennsylvania. The pottery created by the tribe is considered unremarkable.

Some have suggested the Iroquois may have come from the North and slaughtered them. Yet studying the skeletons of the Monongahela people suggest otherwise: There aren't mass cases of severe trauma, only typical wear and tear such as broken bones from falls.

(Kuba stressed in an email after speaking with PhillyVoice that members of the Seneca Nation are working alongside the university researchers when handling the skeletal remains, also noting the skeletons will be repatriated.)

Dr. John Nass, top, and Dr. Cassandra Kuba of the anthropology program at the California University of Pennsylvania.

The same goes for some sort of infectious disease wiping them out. There are signs of general stress on some of the skeletons that may be from infections like syphilis, but Kuba hasn't found evidence of a widespread, devastating illness.

These theories require gathering and identifying artifacts, a task Nass and Kuba have plenty of help completing. Their undergraduate students are treated to plenty of hands-on experience in the field and handling uncovered items, something not afforded at bigger and more prestigious programs.

"If you think about Pitt or Penn State, they don't always involve undergrads in research," Nass said. "It's graduate, or selective."

At state schools like California, which are under threat of layoffs and possible closures, a priority is placed on undergraduate education.

"We want to immerse our students as in-depth as we can, because this is where we teach them what they need to know," Nass said.

Kuba notes that during her undergraduate education at Arizona State University, a much larger institution, she saw how underappreciated undergrads were; most would have been happy cleaning the counter inside a lab, Kuba joked.

"I didn’t want that for my students."

In many ways, undervalued undergrads at an overlooked state school can identify with the very people they're trying to help find. Kuba does.

"People who make their careers (in archeology) are drawn to more fancy sites," Kuba said.

The Monongahela people simply don't have the same appeal as other Native American tribes. They led "hard," unassuming lives, which may be why other experts in the field haven't been drawn to solving their mystery.

Not so for Kuba, Nass and their students.

"I'm drawn to the more quiet people," Kuba said. "I'm a pretty quiet person."

California University of Pennsylvania/Dr. John Nass

California University of Pennsylvania/Dr. John Nass California University of Pennsylvania/Dr. John Nass

California University of Pennsylvania/Dr. John Nass