April 04, 2016

Credits/Justice Bennett and James Faunce

Credits/Justice Bennett and James Faunce

Three local experts all have the same message when it comes to dealing with a friend who is depressed, has suicidal thoughts, or change in behavior: Tell someone.

Defeated.

Disconnected.

Suffering.

Desperate.

Hopeless.

Andrew Miller stood in the middle of a forest attempting to hang himself on May 22, 2013.

Two years before, Andrew was a senior at Malvern Preparatory School in Chester County and headed to college on a full academic scholarship, but classes were never really his thing.

Related: N.J. suicide prevention bill in memory of Penn student passes Senate

Andrew never had a drink of alcohol or rip of a bong during high school, but by the time he reached second semester of his freshman year at college, he was using drugs heavily.

“The first time I got high...one of the first thoughts in my head was ‘my God I should really not ever not feel like this,” said Andrew, whose name has been changed to protect his family and friends.

“I was just a fan of feeling good, and I would do anything to feel good.”

By his sophomore year he was addicted to cocaine and selling pot, pain medications, Ecstasy, and cocaine for some friends on his campus.

His education fell by the wayside.

“When I decided that I just wanted out, I really stopped battling … and just kind of gave myself over to feeling completely hopeless and alone.”

His grades were not meeting the requirements for his academic scholarship, but he said the college never addressed his declining grade point average, so his grades continued to falter. Ultimately, he finished his last semester at college with a .7 GPA.

He was barely going to class, and when he was – he was usually high.

Andrew didn’t want people to know about the drug and alcohol use, though. He wanted to keep up the facade of the outgoing, wholesome, good kid that everyone knew back in high school. Not even his parents knew the true extent of his struggles.

“It’s not that they were blind,” Andrew said. “It’s that I was blinding them.”

Even in high school, before his challenges with drugs and alcohol, Andrew said he felt he was unable to develop meaningful relationships.

“Through high school – even before high school … I had felt like I couldn’t be myself, like I couldn’t be honest,” he said.

He said he saw a therapist during high school, but he did not work at therapy, and was able to convince his parents and others that he was OK.

The double life in college wore on Andrew, and his drug use, specifically cocaine, was unsustainable.

“I couldn’t continue to survive how I was because the drugs weren’t really working anymore,” he said. “Just physically it stops eventually, and you have to do so much [cocaine] just to feel OK.”

He did not feel like he could tell anyone that he needed help.

“Suicide has become more accepted as a solution for people … especially those with an incurable disease, and that probably filters down into people’s mindsets in general that if you don’t think life is worth living, suicide is an acceptable solution.” – Dr. Dan Romer, director of Penn's Adolescent Communication Institute

“I felt completely alone,” he said. “I felt like there was no way to connect to anyone, even if I had really wanted to.”

Without help and the drugs wearing off, Andrew decided in April to take his life, and on May 22, 2013 he set out into the woods, never intending to return.

“When I decided that I just wanted out, I really stopped battling … and just kind of gave myself over to feeling completely hopeless and alone,” Andrew said.

Andrew did not show up for any of his work or school obligations that day, which was irresponsible, “even for me,” he added.

His friends searched until they found him in the woods, attempting to kill himself.

“I was unable to complete that act,” Andrew said. “I was vacant and sort of defeated [when my friends found me] … I was sort of stuck.”

His friends took Andrew back to his house and called an ambulance and Andrew’s parents. At the hospital, he was put under a 24-hour watch period for three days. There, he spoke to his parents for the first time after his attempt at suicide.

“My parents came in and they were terribly upset but happy that I was existing, and basically said ‘anything you need to do at this point, we’ll be here,’” Andrew said. “At that point I told them everything that was going on.”

A nurse at the hospital approached Andrew with an ultimatum: either admit himself to a psychiatric hospital with a special focus on drugs or she would have to forcefully do the same thing, which would result in it showing up permanently on his mental health record.

He chose the first option.

“It kind of felt like [an asylum],” he said. “There were people that I thought were just flat-out crazy.”

Andrew didn’t really feel out of place, though.

“After about the first day I realized that I was there for a reason,” he said. “Whether or not I felt like I belonged, I was there and that hadn’t happened by accident.”

When he left that facility, he went to an in-patient institution to help with his addiction.

Andrew has been sober since that nearly fatal day.

The percentage of students who seriously consider suicide or make a plan for suicide decreased from 1991 to 2007, but has since started to increase, the study said.

Dr. Dan Romer, director of the Adolescent Communication Institute at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center, believes the increase is due to the recession.

“If you look at suicide rates across all the ages in 2008 they all went up,” Romer said. “The economy affects everyone.”

Romer also believes there is some merit in the idea that suicide is less taboo than it used to be and that as a result, suicide rates are higher.

“Suicide has become more accepted as a solution for people … especially those with an incurable disease,” Romer said, “and that probably filters down into people’s mindsets in general that if you don’t think life is worth living, suicide is an acceptable solution.”

“You can go to your school right now, say something about somebody in front of your whole school in two seconds and you can’t take it back really. And then you have those idiots that chime in (and) say ‘Well, why don’t you just kill yourself?’” – Dr. Matthew Wintersteen, Thomas Jefferson University, on the effect of social media

In the Greater Philadelphia area, suicide has been in the headlines often recently, with six student suicides in 13 months at the University of Pennsylvania and Cayman Naib, the 13-year-old Shipley student whose body was found after hundreds joined in a four-day search.

In 2015, 60 Chester County residents died by suicide, which is the most in at least the last 25 years, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Health EpiQMS database.

Tracy Behringer, community outreach and education consultant of the Chester County Mental Health / Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities office, said the actual number of suicides is even higher.

“Suicide is often underreported,” Behringer said. “Even though the information we have are confirmed suicide numbers, it’s probably not all-inclusive.”

Dr. Matthew Wintersteen, of Thomas Jefferson University and co-chair of the Pennsylvania Against Youth Suicide Prevention Initiative, supports that claim.

“To rule a death a suicide, you need really compelling evidence,” Wintersteen said. “It’s hard to get a real grasp of the number of suicides. It’s probably underestimated, but we don’t know by how much.”

The growth of social media – like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram – is another possible explanation for the increase of youth suicides since 2007.

The potential negative effects of social media were especially highlighted in the death of Madison Holleran at the University of Pennsylvania. Holleran, 19, a New Jersey resident, jumped from atop a parking garage to her death in 2014. She left behind a note and gifts for family members, who shared the information with the public in an attempt to bring awareness to depression and suicide.

Holleran's life on social media portrayed a happy girl with everything together, pointed out by ESPN, although behind her social media persona she was strugging with her adjustment to Penn.

Social media use went from nearly nonexistent in 2004 to almost universal in 2010.

Social media, and most specifically Instagram, is host to a specific teenage culture that shows only the best of oneself – your best smile at a dance with your happy date, your best selfie, your best competition. Teens may not share their ugly pictures and saddest moments with people on Instagram – just like Holleran.

In an interview with HuffPost Live, clinical psychologist Ramani Durvasula said, “We engage in social comparison, but [teenagers] are sort of comparing these ideal selves,” he said. “It’s a contest to see whose ideal life is better than the other person’s.”

Wintersteen thinks social media also plays a role with cyberbullying.

“You can go to your school right now, say something about somebody in front of your whole school in two seconds and you can’t take it back really,” Wintersteen said. “And then you have those idiots that chime in (and) say ‘Well, why don’t you just kill yourself?’”

.

A survey of almost 2,000 middle school students, published by the National Institutes of Health, found that students who were cyberbullied were twice as likely to attempt suicide.

But Wintersteen also pointed out there are several benefits of social media when it comes to youth suicide.

“Social media can be really helpful because it gives you an opportunity to express how you feel,” Wintersteen said. He also mentioned the ability for easier connection between many people who are suffering.

Romer, who studied the effect of social media and online discussion forums on youth suicide, found that social media platforms where students mostly talk to friends and family are not risk factors, and provide a lot of support.

“We think that [support] counteracted the possible negative effect,” Romer said.

Another study that analyzed chat rooms and social media effects on youth suicide published by the National Institutes of Health is more conclusive about the effect of social media. “In sum, evidence is growing that social media can influence pro-suicide behavior,” the study stated.

Romer said his 2011 study “advocated that organizations and the government should be more proactive in putting information online for people who are alienated… [and] who are going online and looking for support.”

But with the speed in which technology is changing, Romer said, “You’ve got to be constantly looking for ways to counteract.”

In the end, social media presents new threats, and opportunities for preventative measure. Until there is more information and research done on the issue, the field remains inconclusive about the effect of social media on youth suicide rates.

Suniya Luthar, Ph.D., now a professor of psychology at Arizona State University, set out to study trends of misbehavior in low-income families in the late 1990s. As a comparison group for her study she used families from a private school in an affluent suburb.

In her demographic of households with a median income over $150,000 per year, she found that more of those students had problems with substance abuse and depression than in low-income families, especially in the male population.

The average household income of a Malvern Prep family is estimated to be $311,125, according to an optional, self-reported survey of current parents, done by The Fidelum Group in 2015.

Two of the most proven risk factors of suicide are depression and substance abuse, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

According to Luthar’s study, 59 percent of suburban males self-reported using illicit drugs compared to 39 percent of inner-city males.

By that same study, the percentage of suburban males who suffered from serious depression was five times that of inner-city boys.

“The belief in the past was that those kids from your higher socio-economic families can’t be suicidal, like ‘look at all the benefits they all have? You’re driving around in a Range Rover at 16 years old, how could you be depressed?’” Wintersteen said. “You have to look at what’s behind all of this. There’s a belief you have to be really good.”

Wintersteen related the concept of socio-economic status effect on suicide rates to suicide rates for medical students. Medical students are one of the most at-risk student populations, Wintersteen said.

“They’re so used to doing really, really well, but then you get put in the context of a lot of other people who also do really, really well,” Wintersteen said. “And suddenly you’re not the best anymore and you spent your whole life being the best.”

Wintersteen believes there can be that sort of culture on the Main Line.

“There’s a lot of pressure to do really well – some of that is self-imposed and some of which is other people,” Wintersteen said.

Wintersteen doesn’t believe that pressure is exclusive to wealthy suburbs, however. “For inner city kids there’s a huge push … to make something for yourself.”

In Hollywood, American boys are fed a perception of masculinity with stars like Vin Diesel, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson and Liam Neeson. Being a man means being bold, courageous, strong and powerful. Often those stars are shooting guns on the big screen.

In the music industry, American boys are enthralled by songs of difficult lives of drugs, alcohol and sexual conquest.

According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, boys are four times more likely to commit suicide than girls, and our society’s expectations of men to be “manly” could be the reason.

Dr. Dorothy Sayers, school psychologist at Malvern Prep, said the difference in suicide rates for males versus females comes down to two things: impulsivity and method.

“Boys are much more aggressive in how they make an attempt and boys are more impulsive,” Sayers said.

“You can teach anyone … three basic steps to help someone in an emotional or psychological crisis.” – Tracy Behringer, community outreach and education consultant, Chester County Mental Health

That aggression may come, in part, from the downpour of imagery associating manliness with toughness and force.

Wintersteen believes it almost entirely a result of method, and not really impulse at all.

“High school is all about how you fit in and there is this interpersonal struggle like ‘who do you hang out with?” he said. “I think girls get it just as much as guys get it, but at the end of the day it comes down to boys are more likely to use guns.”

Wintersteen referenced a study that analyzed the difference between teenagers who were in the hospital after surviving a suicide attempt and teenagers who died from a suicide attempt. The main difference between the two was not socioeconomic status, race, or anything else – only whether there was a gun in the house. Children from households with guns who attempt suicide are two-and-a-half times more likely to kill themselves, according to that study.

According to Wintersteen, 67 percent to 80 percent of suicides by firearm are from guns within the house. As a result, Wintersteen had a message for any parents who have a gun in the house and a kid who is struggling: “Ask yourselves the question, ‘How would you feel if your child shot themselves with your gun?’” he said.

With non-firearm methods such as suffocation or poison, more common among teenage girls, there is a time to regret an attempt and survive it by calling 9-1-1 or telling someone. But with a gun, there is no time for regret.

Starting with the current school year, Act 71 of Pennsylvania law requires every public school teacher in the state to have four hours of professional suicide awareness training every five years.

Malvern Prep is not legally obligated to follow that law because of its independent school status. Faculty and staff received a Crisis Management Suicide Policy and Procedures document which outlines the steps they should take if a student threatens harm to himself and/or others, according Neha Morrison, director of human resources. Faculty and staff must read through the policy every year; however, they do not train to the Act 71 standards.

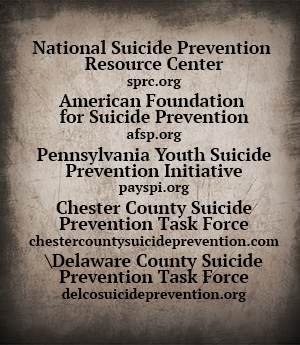

Organizations such as the Chester County Suicide Prevention Task Force (CCSP) are a major source for professional development in youth suicide awareness.

According to CCSP's Behringer, the organization offers several free trainings at major public schools in the area that send students to Malvern Prep – such as the West Chester Area School District.

Sayers, Behringer and Wintersteen all had the same message when it comes to dealing with a friend who is depressed, has suicidal thoughts, or change in behavior: Tell someone.

Behringer, who has been with CCSP since its inception in 2005, is a certified trainer of QPR, or “Question, Persuade, Refer.”

QPR is one of only 12 suicide prevention programs or interventions nationwide that have met the rigorous quality of research and dissemination requirements to be deemed “evidence-based.”

QPR teaches how to recognize the warning signs of suicide crisis, how to offer hope, and how to get help to save a life.

“You can teach anyone … three basic steps to help someone in an emotional or psychological crisis,” Behringer said.

The program, which lasts a little under two hours, can certify teachers, students or anyone else to be an official gatekeeper. A gatekeeper is someone in a position to recognize a crisis and the warning signs that someone may be contemplating suicide.

Beyond the county level, there is also the Pennsylvania Against Youth Suicide Prevention Initiative (PAYSPI), a network of people from the academic and clinical sides, but also survivors and government employees who all work to reduce youth suicide in Pennsylvania.

PAYSPI offers lots of resources for ACT 71 as well as an annual PSA contest for high school students based around youth suicide prevention.

Sayers, Behringer and Wintersteen all had the same message when it comes to dealing with a friend who is depressed, has suicidal thoughts, or change in behavior: Tell someone.

“We don’t recommend that adults or kids keep it to themselves,” Behringer said. “It’s too much for an adult, let alone an adolescent.”

Often times, students may confide in their friends after making them promise not to tell out of fear for potential consequences. Even in those cases, they all say a student absolutely needs to tell someone.

Wintersteen has seen students who knew about a suicidal friend and didn’t say anything.

“That student has a lot to carry,” Wintersteen said. “You don’t want to be that kid.”

Brad Harkins, a member of Malvern Prep's Class of 2004, came home from kindergarten with his best friend on May 15, 1992, like any other day.

Brad’s mother, Carol, now the co-chair of CCSP, had been out shopping when she got a call that her ninth-grade son Jim did not show up to his Downingtown Area School District school that day. She drove home and asked Brad to go up and check on Jim and see if he was OK and just decided to play hooky for the day.

He returned downstairs to report to his mother that his 15-year-old brother Jim was asleep, but Jim was dead.

Jim was a three-sport athlete and an absolute goofball, Carol said.

Jim was the type of kid that would wear a shirt and tie when his baseball team had to, but against societal norms he'd wear them with gym shorts.

“He was absolutely larger than life, funny, that kind of thing,” Carol said. “But he was also very serious about what he wanted to achieve and was hard on himself.”

Her favorite picture of Jim has him on the sideline of the soccer field with a Georgetown bucket hat on his head, before bucket hats re-entered the realm of “cool.”

Jim succeeded on the baseball diamond, soccer field, basketball court, and in the classroom.

“The grieving process really doesn’t stop. It kind of just dwindles, and you can cope with it throughout time.” – Brad Harkins, on coming to terms with his brother's suicide

“He was always in a sport,” Carol said. “He had just made the American Legion [baseball] team and was playing travel soccer.”

During his freshman year, his grades started to slip a little bit and Carol started to become aware that he was drinking alcohol. His travel soccer team was breaking up. Most of Jim’s friends had girlfriends at the time, and Jim was disappointed that his date to the freshman dance wasn’t his girlfriend.

“They were really the normal teenage struggles,” she said.

Now, it is evident that may not have been the case. Carol believes that Jim may have had slight undiagnosed ADD, and depression that he never voiced.

Jim decided not to go to school that May day in 1996, the day of the freshman dance. Instead, he shot himself with his father’s handgun.

After finding Jim, Carol told Brad that some terrible accident had happened with Jim and immediately called 9-1-1.

“I was just in like total shutdown mode – like there, but not there,” she said.

The first few days and weeks were tough for the Harkinses.

“For a long time, you just feel like you’re in an alternate reality,” she said.

Carol couldn’t eat or sleep for the first few weeks, and the grief was actually physically painful. She was almost just totally shut down, and the only thing that lifted her out of it was that she had another son and daughter to care for.

There was an abundance of love and support from the community after Jim’s death, she said. The funeral Mass at their parish, Saints Philip and James in Exton, was overflowing.

“It was amazing to me, the support that we received,” Carol said.

She didn’t feel that there was any external stigma and no one really said anything insensitive, but she felt a stigma anyway.

“You still just feel like ‘Well, what’s wrong with us?’” she said.

Carol eventually had to explain to Brad and her then-middle school daughter that Jim had taken his own life.

They all went to group counseling sessions and became involved with a group called The Compassionate Friends, an organization that helps provide grief support after the death of a child.

Naturally, she tried to be strong and protect her children from seeing her cry. She also believes that her children did the same thing for her. Their family grief counseling sessions and time with The Compassionate Friends were their ways to express their feelings and move along in the grieving process.

“The grieving process really doesn’t stop,” Brad said. “It kind of just dwindles, and you can cope with it throughout time.”

Carol went back to school at Immaculata University the fall after her son’s death, and by “no coincidence” majored in psychology.

She later became a peer facilitator in The Compassionate Friends, joined CCSP five years ago, and is now one of the co-chairs of the organization.

Carol finds her work very rewarding now.

“[Giving back] is really the only way to make sense of everything,” she said.

As for Brad, he said that selective memory has successfully blocked out most of his knowledge from his traumatic experience back in 1992. He joined Malvern’s Class of 2004 in seventh grade.

Carol decided to send Brad to Malvern in part because she wanted him in a smaller, more supportive environment after everything he had been through.

Brad found that care in some members of the community. Now a Penn State University graduate, he is an accountant at a local Malvern firm.

A scholarship established in Jim Harkins’ name at Great Valley High School helps a student who lost someone close to them over the past year, his brother said.

Strengthened.

Connecting.

Improving.

Better-than-ever.

Working hard.

Andrew has now started to put his life back on track.

“Now that I am choosing not to cover up who I really am, I have to find out what life as me is going to be like,” Andrew said.

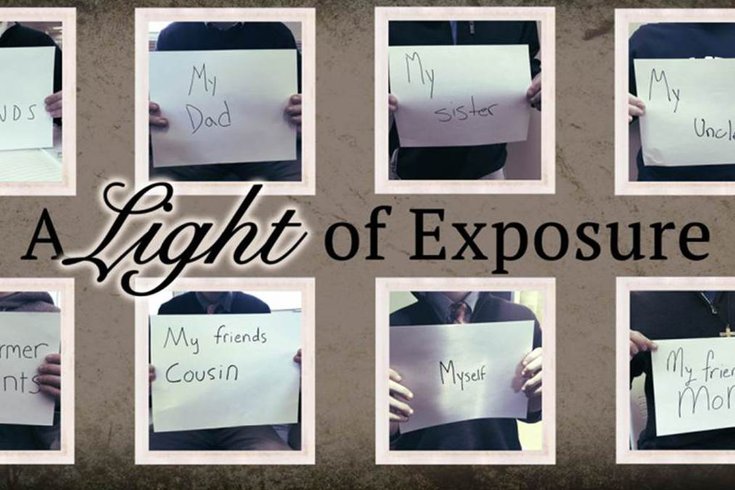

“Shame dies in the light of exposure. Fear of who we are starts to dim in the light of exposure."

Although Andrew never finished his bachelor’s degree, he now happily works in a coffee shop and in retail to support himself.

“I love it because I get to talk to people all day … [and] help solve problems,” Andrew said. “I am challenged and I get a lot of different experiences per day.”

Andrew is starting to develop some meaningful relationships and said he currently meets with a "great" therapist twice a week.

His life still isn’t perfect, but he would never contemplate doing what he did again.

Now 2 years and 8 months sober, the road back hasn’t come without difficulties.

“It’s like going into your closet, taking a lighter and burning anything that you’ve ever worn. Then stripping off the clothes on your back and lighting them up. It’s like being completely naked,” Andrew said. “You have to basically start sewing. You get some fabric from some 40-year-old alcoholic, who is your sponsor, and he gives you the basics. Then you go to your family and they give you some needles. Then you go to some meetings and you get some thread, and eventually you just start sewing until you have something halfway decent to wear.”

He still gets cravings, but he just tries to think about where it would take him. “I think about the long-road it would pitch me on that I would probably not return from,” Andrew said.

Andrew, now without the demons of his double-life, is starting to develop some honesty in his relationships, especially with his parents.

“My parents and I have never been closer … just because I don’t lie to them,” he said, “which I know maybe sounds a little bit obvious, but to me it’s like a total revelation.”

For Andrew, that honesty about feelings and personal struggles is really at the center of it all.

“Shame dies in the light of exposure. Fear of who we are starts to dim in the light of exposure,” Andrew said. “Obviously that’s incredibly painful and difficult, so for me to say, ‘Just do it,’ like I’m in some sort of terrifying Nike advertisement is not realistic. But I think at its core … it’s an issue of honesty.”

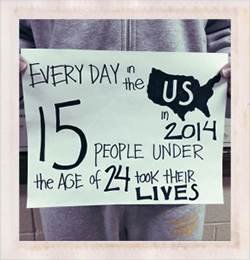

As a society, we aren’t always honest with ourselves about suicide. It can be difficult, gut-wrenching, tense, and emotional, so we avoid honest conversations about warning signs and ways to help. But every day in the United States in 2014, 15 people under the age of 24 took their own life, according to the American Association of Suicidology.

Andrew was and is far from alone.

“It seems daunting almost to say this affects everyone, but in reality, that unites us more than anything,” Andrew said. “It tells us that there are people who have been through the same things. It tells us that there are people that we can talk to that understand these incomprehensible things.”

• • •

Justice Bennett, a senior at Malvern Prep, recently was named the PA School Press Association's Student Journalist of the Year. This story first appeared in The Blackfriar Chronicle, the student newspaper that he also serves as co-editor in chief. You can reach him at his website justicebennett.com or on Twitter at @_JusticeBennett.

James Faunce, a Malvern Prep senior, produced the graphics with this report.

Graphics/James Faunce

Graphics/James Faunce Graphics by/James Faunce

Graphics by/James Faunce