December 24, 2021

N. Currier/Library of Congress

N. Currier/Library of Congress

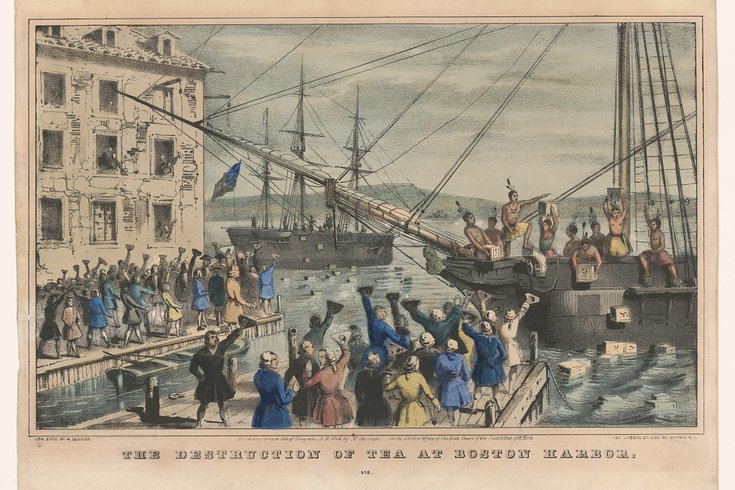

The Philadelphia Tea Party happened on Christmas 1773. Although this protest was a more peaceful act of defiance than the Boston Tea Party, pictured above, patriots in Massachusetts got the idea f for the protest from Philly.

Modern-day Philadelphia doesn't completely shut down on Christmas, and those who have to work on the holiday may be encouraged to learn about another group of city dwellers around during the Revolutionary War era who also didn't take a break on Dec. 25.

Of course, George Washington and soldiers from his Continental Army famously crossed the ice-packed Delaware River from Pennsylvania into New Jersey on the nights of Dec. 25 and Dec. 26 in 1776 to launch an attack that became known as the Battle of Trenton.

But that well-known episode actually occurred on the third anniversary of a lesser-known chapter of the American Revolution involving Philly.

On Dec. 25, 1773, residents of Philadelphia had their own peaceful Tea Party nine days after the first, better known protest happened in Boston.

But the idea of rejecting British tea shipments as a stand against the taxes the empire levied on Americans without representation in parliament had its roots in a meeting Philadelphia patriots held at Independence Hall on Oct. 16, 1773.

That's where several fathers of the American Revolution, including Benjamin Rush and Thomas Mifflin, gathered to draft the eight "Philadelphia Resolutions." They constitute the first example of a public protest against the importation of taxed British tea.

This was a response to the Tea Act the empire passed that May, which slashed the price of the British East India Co.'s tea so it would be cheaper than the smuggled tea most Americans drank at the time.

Purchasing smuggled tea was in part a protest against the Townshend Acts passed in 1767 and 1768, which were meant to help the empire tighten the reins on its North American holdings and impose new taxes on the colonists.

Three weeks after the Philadelphia Resolutions were published, patriots in Boston gathered at Faneuil Hall and adopted them as their own.

"The sense of this town cannot be better expressed than in the words of … our worthy brethren, the citizens of Philadelphia," the Boston group declared.

It was only a few more weeks until the Boston Tea Party happened on Dec. 16. That's when the Sons of Liberty dressed up as Native Americans and forcibly boarded a tea ship docked in Boston Harbor and heaved 342 chests of the import into the water.

The act galvanized the British elite against the patriots' cause and brought the 13 colonies even closer to a war with their imperial overlords.

The Philadelphia Tea Party was carried out very differently than the Boston Tea Party, but was no less effective.

On Dec. 25, a ship called the Polly, carrying 697 chests of tea, docked less 20 miles south at the port in Chester, where it was met by several Philadelphia gentlemen who intercepted the captain and escorted him back to Philadelphia.

The next day, a group of patriots held another meeting at Independence Hall to discuss what should be done with the ship. It was attended by 6,000 people, which made it the largest mass gathering ever held in the colonies at the time.

They ended up passing a resolution stating that the tea should be refused and that the Polly should be sent back down the Delaware River.

The captain decided to turn around and return his tea cargo – which was more than twice as large as the one destroyed in Boston – back to its port of origin in England.

Although the Philadelphia Tea Party was largely non-violent, some say due to the Quaker leanings of the city's elite, the captain and anybody who helped him were threatened with the prospect of being tarred and feathered.

In the mind of Rush, an influential Philadelphia doctor who participated in the quiet act of defiance and eventually signed the Declaration of Independence, the resolutions that led to the Philadelphia Tea Party were the true starting point of the American Revolution.

This was an idea he said he got from John Adams, the nation's second president and a founding father from the Boston area.

"The active business of the American Revolution began in Philadelphia in the act of her citizens in sending back the tea ship," Rush wrote in a letter to Adams. "Massachusetts would have received her portion of the tea had not our example encouraged her to expect union and support in destroying it."