April 07, 2015

It’s college acceptance season, when high school seniors find out which schools have invited them to study on their campus.

It’s a happy time, as students begin to count down the days to graduation and then to arrival at their new college.

Yet, most female students will step on campus in late summer unaware of the danger posed by their first couple of months as a collegian, a challenging, sometimes difficult time when new students are particularly vulnerable as they adapt to living away from home, meet new friends and try to fit in socially.

“It’s good [for students] to know [the Red Zone] is a heightened risk for sexual assaults. It should be conventional not only among administration, but the students, so they have some knowledge of the probability [of sexual assaults].” – Stephen Cranney, Penn researcher

That danger is a higher susceptibility to sexual assault, according to studies.

A 2008 Journal of American College Health study found evidence that young women on college campuses were at higher risk for “unwanted sexual experiences” in their first year, particularly early in the fall semester.

A recent survey of 530,000 male and female collegians at 410 institutions by EverFi Inc., a critical skills education company, found that three percent of them reported a sexual assault in the first four to six weeks on campus.

That period for freshman women between their arrival on campus and Thanksgiving is so fraught with risk of victimization that it has a name: the Red Zone.

Stephen Cranney, a Ph.D candidate in demography/sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, recently conducted research to study the Red Zone hypothesis.

Using self-reported victimization data drawn from 22 U.S. institutions as part of the Online College Social Life Survey, Cranney found the the phenomenon is real, and that the large majority of assaults is almost entirely limited to freshman year.

Many schools use it to highlight the peril that students can face during this time, building it into their health and wellness programming to prepare incoming freshmen at a time when incidents on campus are rising and the federal government has taken a more active role in address the problem.

In November, a Rolling Stone investigation of an alleged gang rape at a University of Virginia frat house put the issue at the forefront of the national consciousness - not because it highlighted the problem but because it was subsequently discredited by other news organizations, and ultimately retracted by the magazine on Sunday.

But within three months of the initial firestorm over the Rolling Stone story, two new allegations of sexual assault have surfaced at UVA. Police are investigating those incidents.

Reports of sexual assault are also under investigation at Florida State University, Vanderbilt University, Columbia University and Duke University, among others.

Last week, a 19-year-old West Chester University student was charged with rape, sexual assault and related offenses after he allegedly sexually assaulted a woman at a party at the Kappa Delta Rho fraternity house.

Indeed, campus rape and sexual assault has become a problem of such proportion that President Obama created a White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault in January 2014.

Last September, as students headed back to campuses across the United States, he launched the "It's On Us" campaign, a new public awareness and action campaign designed to put an end to sexual assault on campus.

To work so hard to make it through the college gates only to be assaulted is "an affront to our basic humanity," the president said at the time.

A number of studies in recent years has clarified the scope of the problem, which many experts consider an epidemic.

More than 95 percent of sexually assaulted students never report the attacks, and those who do often encounter “mystifying disciplinary proceedings, secretive school administrations, and off-the-record negotiations,” the study said.

It also found the following:

• Freshmen and sophomores at greater risk for victimization than juniors and seniors.

• The majority of sexual assaults occurred when women are incapacitated due to their use of substances, primarily alcohol.

• The large majority of victims of sexual assault were being victimized by men they know and trust, rather than strangers.

United Educators, which provides liability insurance to nearly 1,300 members representing thousands of U.S. colleges and universities, conducted a study of sexual assault claims filed between 2011 and 2013 by its client schools. It examined 305 claims from 104 colleges and found:

• 90 percent of victims knew the perpetrator.

• 78 percent of sexual assaults involved alcohol.

• 20 percent of perpetrators were repeat offenders.

• Nearly three out of 4 victims were freshmen or sophomores.

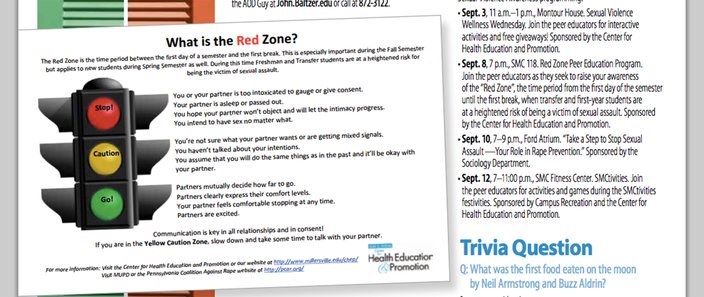

A number of colleges nationwide have embraced the Red Zone term as a teaching mechanism.

• The University of West Virginia defines the Red Zone for its students in a section of its website devoted to sexual assault resources.

• At Texas Southern University, the term and definition is displayed prominently on the cover of a student services guide to “Facts and Tips to Avoid Sexual Assault.”

• A Red Zone awareness event is held on campus at Utah State University to publicize available sexual assault and anti-violence resources available to students, faculty and staff.

Yet, relatively few schools in the Philadelphia region use the term. Those that do say it is a valuable pnemonic to remind students of the dangers.

Dr. Peggy Lorah, director of the Center for Women Studies at Penn State University, said she believes there is a benefit of having a label to identify how serious this time is for freshmen.

“’Red Zone’ means danger: be aware, so it’s a phrase that grabs people’s attention,” Lorah said.

Millersville University has decided to build awareness around the term.

As part of its six-week violence prevention programming, week one focuses on the Red Zone. The university hangs red dots around campus that highlight facts related to sexual assault. Near the dots, posters educate students about the Red Zone. Peer educators on campus also distribute information to students directly on how to keep safe during that period.

Using the term throughout all college campuses might be beneficial, but some schools are skeptical of its connotations, saying it relates too closely to the football term where “teams can score,” according to Jayme Trogus, director of the Center for Health and Education and Promotion at Millersville.

Trogus said one of the main reasons her institution talks about the Red Zone exclusively is because it eliminates some of the misconceptions students might have, and instead, gives them information they need so they can think critically in different situations.

“You can be exposed to different things in college that you might not have [in high school],” she said. “Giving freshmen the right information and having conversations with students so they can make better choices for us, is natural.”

Some programming at the Lancaster County school includes both passive and active education. This requires training peer educators in sexual violence and giving them information on the Red Zone so they can talk about it in a formal way. Earlier in the semester, more active programming, like a mini golf set-up, is used as a way to attract students and start the conversation. For example, students learn about what constitutes consent, their new environment, drug and alcohol safety, and sexual assault.

Angie Marpoe, a junior and Millersville peer educator, said there needs to be some talk about the Red Zone.

“I think it is important to teach other students on campus sexual assault violence is alive and well in this world,” she said. “Perpetrators use this knowledge and lure in their victims this way.”

For most people, “Red Zone” is a football term, describing the area between the 20-yard-line and the goal line. A team that has the ball on that part of the field can be said to have a statistically higher chance of scoring.

The term has no real significance in the game, existing mostly to promote game statistics, hype the psychology of the game and sell commercial advertising. The NFL even has its own RedZone channel where gameday coverage whips around from stadium to stadium to focus on scoring opportunities.

Under the subheading, “Students should take special precautions,” Warshaw wrote:

For first-year college women, the Red Zone of danger is the period of time between move-in day and the first holiday break. Again and again, women are raped during these weeks by men they meet on campus. Why? These young women are good targets because they don’t know campus routines or geography, they’re feeling insecure and alone, yet may be eager to test the limits of a parentless society by drinking heavily and partying enthusiastically - behavior that will win them social approval.

Because the Red Zone is also the time when fraternities and sororities “rush” for new members, there may be parties every night of the weekend (and some during the week as well). Those parties are likely to bring first-year women in contact with upperclass men, some of whom delight in “scoring” with the naive newcomers.

Cranney, the University of Pennsylvania researcher, for one, supports using “Red Zone” as a unified term across institutions, saying it could better prepare freshmen for when they get to campus.

“It’s good to know [this time period] is a heightened risk for sexual assaults,” he said. “It should be conventional not only among administration, but the students, so they have some knowledge of the probability [of sexual assaults].”

As Warshaw tried to highlight the hidden dangers of the Red Zone in her book, the effort to shine light on the hidden problem of crime on U.S. campuses started after a local tragedy nearly three decades ago.

A year later her parents, Connie and Howard, founded the Wayne-based Security on Campus (since renamed the Clery Center for Security on Campus), a nonprofit organization, to address the problem of colleges failing to inform students and parents about rising numbers of violent and non-violent incidents on their campuses.

The Clerys sought uniform laws to improve the reporting of college crime, and in 1990, the Crime Awareness and Campus Security Act, (subsequently renamed the Jeanne Clery Act), was passed.

The law requires colleges and universities to disclose their security policies, keep a public crime log, publish an annual crime report and provide timely warnings to students and campus employees about a crime posing an immediate or ongoing threat to students and campus employees.

It also ensures certain basic rights for victims of campus sexual assaults and requires the U.S. Department of Education to collect and disseminate campus crime statistics.

The tide of federal complaints against colleges began in 2011, when the Obama administration said Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 would be interpreted to include new responsibilities, all the while noting that many schools were already violating the earlier version in their handling of sexual assault cases.

From then on, as outlined in an April 2011 letter, the Office for Civil Rights considered “sexual harassment of students, including sexual violence, interferes with students’ right to receive an education free from discrimination and, in the case of sexual violence, is a crime."

In fact, as of April 1, 2015, 106 colleges and universities have pending investigations by the U.S. Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights for possible violations in their handling of sexual assault cases under Title IX, a federal law that guarantees gender equity. Among those post-secondary institutions that have pending sexual violence cases: Penn State University, Swarthmore College, Franklin & Marshall College, Elizabethtown College, the University of Delaware, and Temple University, which has two cases.

Princeton University resolved a Title IX violation last fall. OCR found the university failed to promptly and fairly respond to complaints of sexual violence. In addition, the policies and procedures used by the university to investigate and respond to assaults and violence did not comply with Title IX. By agreement, Princeton subsequently implemented new policies and procedures to correct many of the deficiencies identified in the investigation.

In addition, the Federal Government mandates that colleges and universities provide programming for parents and students so that before they even step on campus, they are familiar with policies, protocols and have an idea what to expect within the first year.

Despite the programming offered by many schools, some students still remain concerned about how sexual assault cases are handled throughout universities and say even more should be done to make freshmen aware of the possibility of victimization on campus.

Brittah Brown, a 21-year-old junior at Temple University, said there “definitely” should be more schools informing freshmen about the Red Zone.

“Anytime I was at a party [as a freshman] I was leered at, grabbed or made to feel unsafe,” Brown said.

Maggie Wurst, 19, said there needs to be more of an emphasis on sexual assault on campus. She also said that Temple is headed in the right direction because of their counseling services and prevention programs for students.

“I think that it is more common to meet someone who has been sexually assaulted or harassed at Temple, than someone who has not,” said Wurst.

While Temple does not have specific programming on Red Zone awareness, it does focus on a variety of subjects that are crucial for incoming freshmen, including an overview on mental health, well-being, the use of drugs and alcohol, and interpersonal violence and sexual assault, according to Kimberly Chestnut, director of the Wellness Resource Center at Temple University in Philadelphia.

“It’s not that we weren’t aware of [the Red Zone],” said Chestnut. “We are connected with knowing this is a concern but we have broadened the way we address it.”

Colleges can take matters into their own hands by better addressing – as early as possible – the dangers students might face, and giving them the resources they need.

Whether or not this means emphasizing the Red Zone is a decision for each college to make, said Trogus, the Millersville University administrator.

“Find what works best for your college,” she said. “It’s important to see that the programming is working.”