June 03, 2022

Albert Lee/City of Philadelphia/Flickr

Albert Lee/City of Philadelphia/Flickr

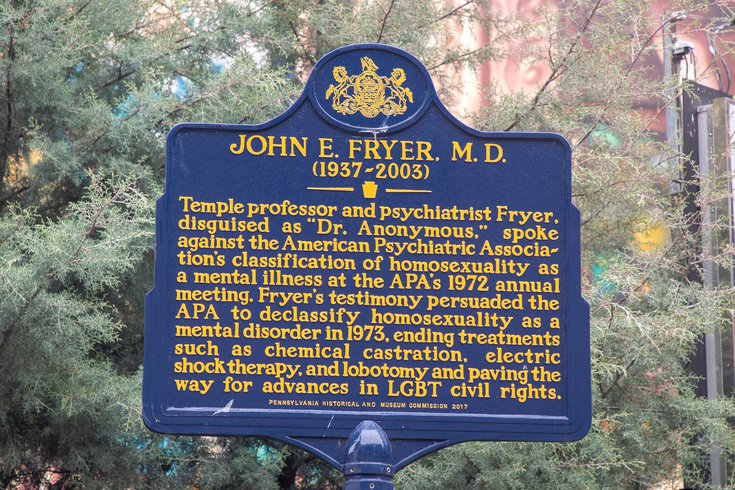

Dr. John E. Fryer changed history at the 1972 convention of the American Psychological Association by declaring, 'I am a homosexual. I am a psychiatrist.' The following year, the APA declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder, paving the way for future fights for LGBTQ rights. Above, a Pennsylvania historical marker in Philadelphia honors his contributions.

Homosexuality was listed as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual — which psychiatrists use to diagnose patients — until 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association declassified it.

Among those chiefly responsible for the decision? Dr. John E. Fryer, a gay psychiatrist who spoke out at an APA convention in 1972. Disguised with a mask and a voice modulator, Fryer — who used the alias "Dr. Henry Anonymous" — said a few simple words that changed history.

"I am a homosexual. I am a psychiatrist."

At the time, being out as a gay man would have meant the end of Fryer's career. In 1965, Fryer was terminated from his psychiatry residency program at the University of Pennsylvania because a program administrator discovered his sexual orientation. He eventually completed his residency at Norristown State Hospital before beginning a career in teaching at Temple University.

Though Fryer's contribution to LGBTQ history is significant, he is not particularly well known. His participation at the APA convention was part of a larger lobbying effort by Philadelphia-based gay rights activists Barbara Gittings and Frank Tameny, who demonstrated at the annual convention in an effort to encourage the APA to delist homosexuality as a mental illness.

Fryer was chosen primarily because of his profession — having a psychiatrist come out on stage and tell a crowd of people that homosexuality is not an illness was unheard of during this time. However, Fryer was hardly the only gay psychiatrist at the convention. He frequently joined secret meetings of a group called "Gay P.A.," which was comprised of other closeted psychiatrists. Many of them were in the room when Fryer made his historic speech.

"Support groups like that were exceedingly rare before the 1970s, but started to pop up after Stonewall. Even then, most of the groups were discreet and very quiet," said Bob Skiba, curator of collections at the John J. Wilcox Archives at the William Way LGBT Community Center. "The most distinct and most closeted of those was the Gay P.A., because it would have been professional suicide to come out at that time."

It has been 50 years since Fryer made his speech on May 2, 1972. His participation in the convention put in motion a range of other fights for LGBTQ rights in the ensuing five decades.

"As psychiatrists who are homosexual, we must look carefully at the power which lies in our hands to define the health of others around us," Fryer said in his speech. "In particular, we should have clearly in our minds our own particular understanding of what it is to be a healthy homosexual in a world which sees that appellation as an impossible anachronism — one cannot be healthy and homosexual, they would say."

In 1972, Dr. John Fryer testified as 'Dr. Henry Anonymous' before the APA, risking his career to tell psychiatry that being gay should not be equated with mental illness. https://t.co/PoZa16jGxC pic.twitter.com/aokJ6LdAuE

— Medscape Psychiatry (@MedscapePsych) May 7, 2022

In 2018, the Pennsylvania Historical Society commissioned playwright Ain Gordon to visit the archives and write a play based on some of the findings. Amid drafts of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence were stepping stones to Gordon finding a PDF of a small yellow piece of paper, which contained Fryer's speech.

"The thing that's really intense is that the speech is very level-headed on paper, and not imbued with the incredible level of personal risk he was taking," Gordon said. "To realize that the man risked his entire livelihood — he would have his license taken away, he would never be able to work again, he would not get tenure, he could be imprisoned, he could be called mentally ill — to realize that the man risked everything in his life in that moment is hard for us to imagine."

Gordon took the paper to the front desk of the archives and asked whether they had any more information about it. The Historical Society did have some more documents about Fryer — 217 boxes worth of letters, case files and other documents that painted a picture about the psychiatrist's life from beginning to end.

Rather than write a play starring Fryer, Gordon wrote from the perspective of three people featured prominently in the stacks of documents. Among them were Fryer's father, a Christian man from Kentucky who never spoke of his son's sexual orientation; Lauren Luder, Fryer's secretary and closest friend; and Alfred A. Gross, a gay social worker in New York City who shared correspondence with Fryer.

Throughout the play, audiences learned about Fryer and his contributions to culture and history through the lives of the other characters in his life. In particular, Gordon focused on Fryer's father as a way to discuss the speech itself, honing in on the inherent risk in Fryer's decision to speak out at the APA convention, despite being disguised.

"As long as all queer people were mentally unsound, all litigation would fall apart," Gordon said. "To me, it's crucial to understand the stepping stones along the way — both good and bad — that led us into the fight that we are in now, which in fact is more in peril than it has been in a long time. I think historical context is important whenever you're in battle, to understand what has and hasn't been done before."

Fryer was honored on the 50th anniversary of his speech with a commemoration ceremony in the Gayborhood. Mayor Jim Kenney spoke along with officials from the APA and Historical Society of Pennsylvania about Fryer's legacy on LGBTQ rights and the ongoing right for equal treatment.

The relationship between the LGBTQ community and City Hall hasn't always been positive, Skiba said.

"As a longtime activist myself, the fact that the city was so involved in celebrating this anniversary shows how far we have come, because this would not have happened even 20 years ago in Philadelphia," Skiba said. "The relationship between the gay community and City Hall has always been checkered, but it has improved remarkably over the last two decades, which I think is a huge stepping stone for the community."

In 2017, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission dedicated a blue historical marker to Fryer, which stands near the corner of 13th and Locust streets in the Gayborhood. The marker notes the historic significance of the APA's decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder, which ended treatments like chemical castration, electric shock therapy and lobotomy.

Earlier this year, Fryer's Germantown home, where he lived until his death in 2003, was added to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places.