February 14, 2018

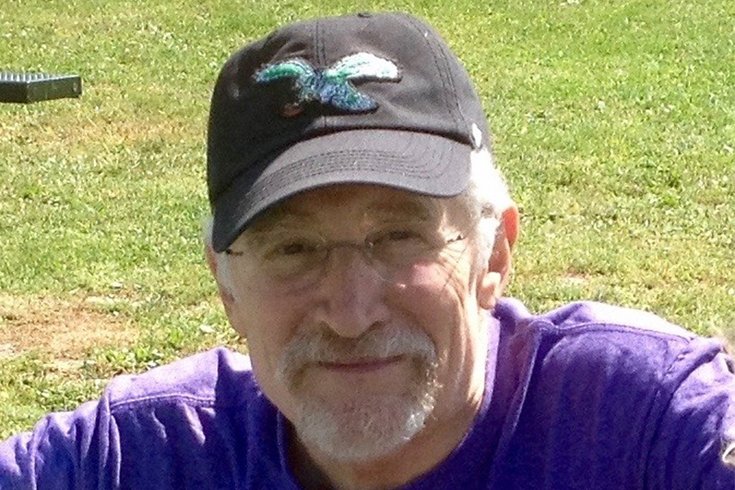

Photo courtesy/Albie SInger

Photo courtesy/Albie SInger

Albie Singer went to his first Eagles game in 1956 at Connie Mack Stadium. On Dec. 26, 1960, he was in the stands at Franklin Field with his father and brother to see the Eagles defeat the Packers, 17-13, for the NFC Championship. "Who knew then it would take 57 years to recreate this moment for the city?" he wrote from his home in upstate New York. "A lifetime for many."

The passage of time melts away like snow under a warm sun when current events trigger memorable moments of the past…like a Beatles’ song that evokes thoughts of old college friends, or going to a specific place that reminds you of past traumatic or seminal events. Sunday while watching the Super Bowl, I might have been in upstate New York, but my heart and soul were back Philadelphia. Thomas Wolfe, you can go home again, or perhaps you never really leave.

During the fourth quarter of that most scintillating of games, while I paced like a caged leopard in my Glenville, New York living room, I could hear the collective cheers and sighs of Eagle fans and knew, like mine, millions of hearts in Philly skipped a beat when the Patriots went ahead in the fourth quarter.

I was sharing last Sunday’s Super Bowl experience with my twin brother, my lifelong Eagles partner, who was on the phone from his home in New York City. Once upon a time, he and I, both diehard fans, joined my now-departed father at the Eagles' last championship, against Green Bay in 1960. For a brief moment near the close of last Sunday’s game, Dad was there in my living room, cussing and cheering just as he did when we were young. As the last seconds of the game wound down, Tom Brady heaved a high prayerful aerial toward the goal line. Time froze in the futuristic, glass-enclosed Minneapolis stadium. The ball fell harmlessly to the blue-painted end zone turf amid a scramble of arms, legs and bodies – sealing the Super Bowl victory for the Philadelphia Eagles, and just then I flashed back to venerable, Gothic, all brick-and-steel Franklin Field on that day after Christmas 1960, when Chuck Bednarik sat on Jimmy Taylor as the clock wound down, preserving an Eagle win.

The 57-year wait was over.

John Kennedy had been elected president to succeed World War II hero Dwight Eisenhower a month before the Eagles met the Packers for the NFL title on a clear, cold day, the field in the old stadium bordered by ice and snow that had been removed due to a blanketing snow just two days before. The NFL was just becoming a national phenomenon propelled by the now-iconic Baltimore Colts-New York Giants championship game of 1958 – won by the Colts when Alan Ameche took a hand-off from Johnny Unitas and crashed into the end zone in sudden death overtime.

At that time, about 40,000 fans normally attended games at Franklin Field, where the Eagles had moved from Connie Mack Stadium (it was called Shibe Park then), where they had played in a converted baseball stadium for about 25 years having debuted in 1933 at Municipal Stadium. That serendipitous championship season changed all of that, sparking local football frenzy such that a season ticket became a precious commodity passed down to generations of family members. The Eagles were woven into the fabric of the city as much as Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell and cheesesteaks.

I remember waking up early that December Monday morning more excited than ever...even more than for my Bar Mitzvah, actually a B’nai Mitzvah, a year before. Attending that game was the highlight of my childhood, aside from being born. My dad’s devotion for the Eagles had rubbed off onto us from his telling many a tall tale over a bowl of Wheaties... like the time he (allegedly) walked several miles from the Logan neighborhood in North Philly to Connie Mack Stadium in a blizzard to witness Steve Van Buren plow through the snow for the only score in a win against the Chicago Cardinals… Or how Pete Pihos would literally carry defenders with him after catching passes… Or the exploits of his first hero, the diminutive (for football) quarterback Davey O’Brien, a Heisman Trophy winner from TCU, who played two years with the Eagles in the late '30s.

At halftime we’d go out to back yard and recreate the first-half action, and repeat the routine as soon as the game was over…no matter what the weather. We were hooked – Eagle fans, for life, as it turns out.

The Eagles acted as bonding agent between him and his sons as we shared heroes like Norm Van Brocklin, Chuck Bednarik, Tommy McDonald and Pete Retzlaff. He took us to our first game in 1956 to see the Chicago Cardinals and Ollie Matson at Connie Mack Stadium, but we rarely got to see games live since he worked most Sundays at his carpet business in North Philly. The next year he treated us to a game on my 11th birthday, versus the Lions at Connie Mack where we watched in the upper end zone seats (the first baseline for baseball) as Sonny Jurgensen, a rookie from Duke, took a few snaps. My brother and I watched the road games on TV each Sunday during the fall, and for home games I’d usually sit in my bedroom and listen to Bill Campbell’s broadcasts on my Philco transistor radio. It wasn’t until college that I started going to games on my own, taking in a game at Franklin Field before heading up to school.

1960 was a magical year for the Eagles, winners of 10 straight including heart-stopping wins over Eastern Division rivals New York and Cleveland. During the televised road games announced by Jack Whitaker and Bosh Pritchard, I’d sit on the floor of our Broomall living room with my brother, sometimes announcing games on our Webcor tape recorder – nothing of note, but I wish my mother hadn’t tossed the tapes when we went to college. My brother was a riot often reacting to hard tackles with a loud “Ewwwwwooooooo!” instead a verbal description. At halftime we’d go out to back yard and recreate the first-half action, and repeat the routine as soon as the game was over…no matter what the weather. We were hooked – Eagle fans, for life, as it turns out.

We shared the experience of many “Philly guys” (now of course gals, too) ardently following the Eagles, Phillies, Warriors (the team that preceded the 76ers as the local pro basketball team), Big 5 college hoops, and later the Flyers. You got into a discussion with a guy from Philly and assuredly the conversation would focus on these teams, whichever was in season. Many a boring law school class was spent in the back row talking about Sunday’s Eagles game. It’s as if upon birth in a city hospital you were vaccinated with a dose of sports fever. Despite being avid fans, we had no earthly idea we’d be seeing the championship game live.

Among Albie Singer's vivid memories from the 1960 NFL Championship game: “the way Bednarik, like a stealth destroyer in enemy waters, searched out Packer runners, busted up blocks and caromed into [Jim] Taylor and [Paul] Hornung stopping them dead in their tracks.”

Soon after the Eagles clinched the Eastern Conference title in ‘60 with a win over St. Louis on the road, their 10th straight win, a foot of snow blanketed Philly and the suburbs, burying our driveway. It was so deep our dog walked over the fence in the back yard on a snow drift. My dad didn’t come home from work due to the storm and called the next morning to tell us he’d be home in the afternoon.

“Is the driveway shoveled yet?” he asked.

“No, not yet,” I said, “it’s really deep, Dad; we thought we’d wait till the sun helped soften it up." (Or something like that.)

“OK, but...if you want to go to the championship game...you and your brother better have that driveway clear by the time I get home,” he replied.

“Holy shit.”

While downtown, Dad had gone to the Eagles ticket office on Walnut Street and purchased three $8 tickets to the NFL Championship game scheduled for December 26, the opponent to be decided (either Baltimore or Green Bay who were tied at the time for the Western Division title with a game to play). Sufficed to say, my brother and I shoveled the driveway in record time.

On the morning of the game we drove a back way to the stadium past Merion golf course through parts of Havertown to Lancaster Avenue, headed east toward the Penn campus, parking on snow-lined 38th Street, five blocks from the stadium, and walked with the horde of anticipatory fans to the stadium where provisional bleachers were added to squeeze in 67,000 fans into the 60,671-seat stadium. We arrived and found our seats in Section SJ, row 26, between the 10- and 20-yard line, early enough to see the kelly green-and-white-clad Eagles and the Packers, adorned in white jerseys and gold pants, warm up.

My eyes fixed on Norm Van Brocklin arching passes that sailed like eagles into the arms of Tommy McDonald, Pete Retzlaff, Bobby Walston and others. The seats were even with the pillars that supported the upper stands, so there was no obstruction. Fans of modern stadiums have no idea about these steel beams. I was so giddy, forgot how cold it was.

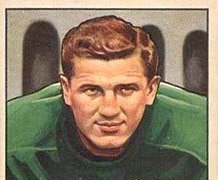

The Eagles' Chuck Bednarik, as depicted in a 1952 Bowman Large football card.

So stymied were the Eagles that I began to think they’d be shut down by this formidable defense. In the second quarter, with the Eagles past midfield and coming toward our seats in Section SJ, suddenly lightning struck. First a nifty pass from Van Brocklin. Rolling right to evade pressure and throwing across his body, he found the elusive McDonald streaking over the middle for a first down near the Green Bay 35. Van Brocklin then dropped back behind great protection and lofted a ball toward the deep sideline, right in front of us. I remember yelling, “he’s open!” McDonald cradled the heat-guided missile with those deft hands of his, got shoved by the defender, and skidded into the end zone, landing in a snow bank. I close my eyes and can still see it. Just like that the Eagles were in business, up 7-6. The noise underneath the upper stands echoing off the brick walls was deafening now, as loud as a subway train pulling into a station. My father was as vociferous and ebullient as I had ever heard or seen him, and each time something good happened for the green and white we’d clap our hands together.

At halftime, the Eagles leading 10-6, we ventured to a concession stand and got hot dogs that only a sports fan could enjoy and hot chocolate that tasted like shellac, but was at least warming on a day that was getting colder. My brother and I now laugh at the fact that our Korvettes-bought black coats and penny loafers weren’t quite up to December football game conditions. Defense prevailed through the third quarter and into the fourth quarter, the Packers taking a 13-10 lead on a Bart Starr to Max McGee slant TD pass at the east end in front of us with almost all of the fourth quarter remaining. My heart beat fast, and the crowd grew restless and pensive.

On the ensuing kickoff, Ted Dean, a rookie, followed a convoy of blockers down the south sideline in front of us past midfield to the Packer 39 that sent an electrical charge through the crowd so raucous I had to cover my ears. Van Brocklin engineered the Eagles with a blend of runs and short passes to the five-yard-line down at the far end of the field going toward majestic Weightman Hall, the U of Penn athletic building that bordered the west end of the stadium. A sweep left, a crushing block, and Dean burst into the end zone for the score that gave the Eagles the lead, 17-13, upon Bobby Walston’s extra point kick.

The national media that ... creates trite stereotypes of the fanbase of Philly completely miss the passion of the city for the team.

But plenty of time was left for a Packer comeback. (When the Eagles took the lead against the Pats, and Brady and company got the ball back with less than 5 minutes left, it felt like déjà vu.) The fans growing more tense and louder with each play, the Packers began a possession with about 4 minutes left and moved inexorably toward Eagle territory. Starr calmly, with short passes against the Eagles' prevent defense, moved the Packers out of the shady side of the field into the sun and treacherously close to the Eagles goal line. The clock up on the facade of the east stands seemed to move in slow motion. Finally, with only 9 seconds left, time for one more play, Starr looked into a congested end zone where Bobby Jackson, Tom Brookshire, Gummy Carr, and Don Burroughs had Packer receivers covered.

The Packer quarterback, who would go onto a Hall of Fame career, dumped a short pass over the middle to Jim Taylor who, like an advancing Sherman tank, shed several defenders. My heart was in up in my throat, headed for the top of my head. Waiting for Taylor at the 9-yard-line was Bednarik, who like a brawny cowboy at rodeo clutched onto Taylor, a determined steer, and wrestled him to the ground. Amid the pandemonium that rocked the old ball yard, Bednarik sat on Taylor until the final gun went off. Jubilation.

Who knew then it would take 57 years to recreate this moment for the city? A lifetime for many.

Amid the joyous, bedlam, we exited the stadium by following the crowd onto the track that surrounded the playing field while some fans in the East Stands were throwing snowballs at police who were trying to stop fans from toppling the goal posts….to no avail. I’ve read recently that several cops were injured dealing with the fans, but I didn’t discern this rumble. As was customary when we got home, my brother and I reenacted the game in our snow-covered backyard, our collie, tackling us whenever he could. Dog was as sure a tackler as Tommy Brookshier.

Fast-forward through 57 years, two spent in the army at Fort Bragg, N.C., two back in law school in Philly, then 44 years in North Carolina, finally the last year-and-a-half here in upstate New York, where a blustery snowstorm out my window evokes memories of that December afternoon in another time. No matter where I was at the time, I’d always watch the Eagles games if I could, listen on radio, or at a minimum check the score. I never went to bed not knowing what the Eagles had done on that day.

Just before going in the army I was at Franklin Field during their abysmal 2-and-12 season, on one particular Sunday afternoon witnessing the infamous Santa Claus snowball game, which at the time was no big deal to me. A few fans upset with the losing season and a scraggly, drunken substitute Santa, fired snowballs in his direction. The national media that focuses on these moments and creates trite stereotypes of the fanbase of Philly completely miss the passion of the city for the team. During my law school days I’d attend games with my dad who had season tickets…but only on days that his wife, my stepmother, wouldn’t go because of inclement weather. The team wasn’t very good during those “white helmet” years, but I’d wake up on a rainy or snowy day, eagerly waiting for my dad’s call. While in the army I’d borrow a friend’s radio and sit in the middle of a barracks with earphones on and listen to games when they were playing the Redskins or were on a national network.

My father had passed away in ‘98, but I felt his presence, especially when I found my seat in the 700 level of the Vet and there was an empty seat next to me.

When the Eagles beat Dallas in January 1981 for the NFC championship, I got in my car and started a one-car parade honking my horn to the disinterested citizens of Raleigh, North Carolina, where I lived for over 40 years. Unfortunately, a dose of what some fans call “suffering” followed that victory, as the Eagles fell flat against Oakland in the Super Bowl that seemed to portend nearly a decade of mediocrity. A missed field goal in '78, in the final seconds of a playoff game at Atlanta, was the first of these distressful events summoned by the gods of football. Three playoff losses in the Buddy Ryan years that produced a grand total of three touchdowns, left a sour, cursed feeling in minds of the Philly faithful, who by now started gaining national attention as a suffering but still passionate fanbase as the team was well into the Super Bowl era without a trophy. The near-misses during the Reid/McNabb era cemented the reputation of the star-crossed team and fans.

About a week before the Eagles faced Tampa Bay for the NFC title in January 2003 a client at my child advocacy office in Durham, N.C. told me of some tickets being scalped by some folks he knew from his hometown of Tampa. Seemed some fans there were chickening out of going to Philly for the game due to the spreading legend of what happens to visiting fans in the midst of rabid Eagle fans. I connected with a person to whom this client referred me and purchased two tickets for 500 bucks, one ticket for my brother. The guy said he and his friends were afraid the Philadelphia fans would attack his bus, he having read of some similar incident.

I flew to New York City, met my brother at his place in the East Village, and we drove down together to Philly on a frigid Sunday. Really frigid. Colder than the ’60 game, 20 degrees with wind chills near zero. Only, we had better clothes to deal with the arctic conditions. We parked the car in downtown Philly and spent a nostalgic hour walking around before getting on the subway to the game. At each subway station hordes of fans were celebrating what they felt was their day of destiny, a sure-fire win over a fair-weather team that would fold in the frigid conditions and send the Eagles to the Super Bowl for a chance at their first title in over 40 years.

My father had passed away in ‘98, but I felt his presence, especially when I found my seat in the 700 level of the Vet and there was an empty seat next to me. (Found out the fan spent the day by the beer concession). My brother sat in the stands below me as the tickets weren’t together. I did join him for the fourth quarter. I wasn’t as optimistic as the frolicking fans about their chances, but that’s my pessimistic nature – developed from watching so many disappointing big games by all the sports teams over decades. I tended to think there was an inordinate amount of pressure in Philly, and that expectations were always too high and premature. I sensed that a big play would turn a rabid crowd to pensive gloom, a collective mood that would affect the team. It was just so Philly.

The Phillies and Sixers had to experience a few near-misses before they won titles in pressure-cooker Philly. I even related to my brother that the crowd would be explosive and deafening at the outset, but get quieted by a big play. Weird things seem to happen in big games there. Just ask the Phillies' Greg Luzinski, who misplayed a ball in the ninth inning of a playoff game with the Dodgers that opened the gates for a 3-run winning rally on a day now known as Black Friday in Philly. Or members of the Sixers or Warriors teams that lost key Game 7s in conference finals three times to the Boston Celtics, twice after leading a series 3 games to 1. Or the Flyers, when they lost not only a 7th game Conference Final to the Jersey Devils, but lost their captain Eric Lindros when he was knocked unconscious by Scott Stevens’ torpedo check at center ice. And the most famous sports disaster of all, the collapse of the '64 Phillies, a 10-game losing streak that began when a Cincinnati Red stole home to win a 1-0 game.

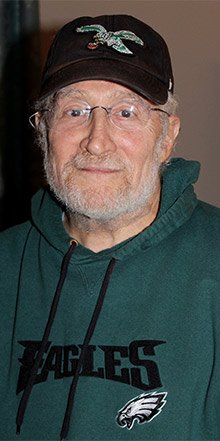

Albie Singer wears his Eagles gear in a photo taken Tuesday.

When Brian Mitchell rocketed up the middle of the field and nearly returned the opening Tampa Bay kickoff for a TD, the old Veterans Stadium concrete bowl nearly crumbled as it vibrated from the tumultuous roar of the crowd. Then Duce Staley rumbled untouched into the end zone … again the stadium rocked – literally the concrete shook beneath my frozen feet. Was it going to be this easy. Was this the year? This mood lasted only to the end of the first period because Joe Jurevicius, a slot receiver, caught a third-and-2 short pass from Brad Johnson over the middle past injured safety Blaine Bishop, and skirted 60 yards down the sideline all the way to the 4-yard-line to set up a Tampa TD that gave them a lead they would not surrender.

Was this that “happening” portending Eagle doom? The crowd, with the Tampa defense dominating McNabb and the Eagled offense, inexorably turned pensive and ornery, just as I had imagined while on the subway. In the early part of the 4th quarter, the Vet became eerily quiet, awakening only when the Eagles, down 20-10, ignited the crowd with a late 4th quarter desperation drive that would have brought them within 3 points with 4 minutes left – enough time to force Tampa after a 3-and-out to punt the ball back to them, giving them a shot for a glorious finish.

The braying wolves in the stands had hope at last. Years of frustration would be wiped away with a heroic comeback. Then the football gods reacted with a vengeance; a McNabb pass targeted to a tight end who appeared open for a fraction of a second in the end zone was picked off by Ronde Barber, who sped unmolested 100 yards to douse the rally and send the Philly faithful into mass depression. I sat there in mournful disbelief with my brother who looked like our father had died again. One fan we had spoken with during the game epitomized the fans who filed out of the stadium. He was obviously drunk and burned out as he sat in his seat, head bowed. He looked over at us and said, “At least you guys saw a championship; what a bummer, man.” In some ways it was a fitting end to the Eagles' 30-year stay at the old decaying Vet, known more for rowdy fans than quality football. The ride back to New York City was somber; at least I got to eat a hoagie on the way home, which we got at a place on Roosevelt Boulevard loaded with Eagle fans who looked as though they had gotten back from a funeral.

The following year, 2003, the team reached the championship game again; however, those same vengeful gods summoned a 300-pound Carolina Panther defensive lineman to pounce on a defenseless Donovan McNabb, crushing his ribs and limiting his performance for the rest of the game, lost by Eagles. In 2005 following a wondrous 13-3 season and getting over the hump with an NFC championship game win over Atlanta, the Eagles came up short against the Patriots and a young Tom Brady, losing Super Bowl XXXIX in Jacksonville.

The loss prompted the city scribes to use the “choke” word toward McNabb and the coach for an unusually slow march to a touchdown in the final minutes, when they were 10 points down and needed to show a bit more urgency. The angry segment of the fanbase even accused McNabb of puking on the field on that slow boat to China touchdown.

In truth, he didn’t vomit, but was exhausted from taking a pounding all day. Did I mention that a substantial minority of Philly fans let their passion run wild while expressing displeasure at players and coaches? Part of the folklore, but in truth, the negativity is no worse than in other big cities. My dad was a fan who not only took losses hard, but would verbally lash out at the coaches or players. I heard the “bum” word a lot growing up.

Watching Carson Wentz in this year’s 14th game at Los Angeles limp back to the huddle after a NASCAR-like collision with two Ram defenders at the end zone, I started getting that old cursed feeling. The Eagles having a banner year, 12-2, winning a Super Bowl a reasonable narrative, and Wentz, capturing the imagination of the fans in Philly and around the nation, was a favorite to win the MVP in only his second year.

Despite the doom and gloom of the press and much of the fanbase (who could blame them). in light of Wentz’ injury and Foles’ less-than-stellar two years away from the team, I did remain resolute in my faith in this team. I’d sensed something in this TEAM that stoked optimism. The way they behaved toward and with one another, the chemistry, the lack of any divas in the locker room, the spirited leaders, the aggressive offensive mindset, the defense that swarmed like hungry hyenas after antelope. With the gifted Wentz at QB the offense was a high-flying trapeze act, the young quarterback breaking Sonny Jurgensen's team TD pass record in just 13 games. The defense displayed the cohesion of a Navy Seals mission.

I didn’t sleep at all after the game, and have been pretty giddy all week .... Haven’t taken off my Eagle sweatshirt, and strut around town proudly with it on.

I took an Amtrak train down the Hudson River from my new home near Albany, and brother and I drove to Philly for an October game against the Cardinals; the game demonstrated the team’s potential, a swarming defense that appeared offended by the opponent scoring anything on them...even when the matter was decided. Surging to a 34-7 lead in front of a raucous crowd that enthusiastically sung the Eagles fight song after each score, they looked “super.” The Cards drove the field toward a late, meaningless touchdown. J.J. Nelson caught a short pass and streaked down the sideline toward the goal, appearing like he’d score. But safety Rodney McLeod rocketed across the field crushing the receiver at the one-yard line and causing a fumble that rolled in and out of the end zone for a touchback. Not here, not now, not ever in our house. The diehards remaining at the Linc loved it, for the effort emblemized the Philly grit.

Super Bowl LII provoked a national narrative about the Eagles 57-year championship drought and the improbability of beating dynastic Tom Brady and the Patriots with Nick Foles, who had replaced Wentz as the Eagle quarterback. Foles’ performance in the rout against Vikings gave the neurotic, starving fans some hope.

The two weeks between the NFC championship and the Super Bowl seemed like months. When it finally arrived, and my brother called on cue, I was affixed in my “lucky” chair, a couple of feet in front of the TV, wearing my Eagle sweatshirt, my belly full of chili and cornbread, and a couple glasses of wine, a rarity since I was diagnosed with diabetes. My wife, not a fan at all, even watched the whole game, exuberantly cheering throughout. I toasted this Eagles team and my father on the 20th anniversary of his death. How fitting for this game to fall on this commemoration. My brother and I both mentioned that it felt like he was “down here with us.”

When the game started, my brother and I were transfixed to every play, trying to predict each Pederson offensive call, (the coach and I were in sync for this one) howling at the Eagles’ big plays, cursing the huge gainers of the Patriots, furious that they were even reviewing the Eagles touchdowns. Paul Simon was right: “after changes upon changes we are more or less the same.”

“Uh-oh, here we go again, just like in 1960,” I mused, for the Eagles forged into a 4th quarter lead (after the Pats had gone ahead for the first time in the game) with a bullet from Foles to the slanting Ertz who dove into the end zone. The Eagles and their fans now had to hold on for dear life and withstand one last gasp from Brady, who had made a reputation for last minute heroics. (I might as well have been back at Franklin Field urging the clock to wind down to 0 as Starr lead the Packers downfield in 1960.) When Brandon Graham crashed through the Pats fortress and knocked the ball out of Brady’s grasp and Derek Barnett gathered it in, 57 years of pent-up hope and frustration propelled me out of the chair and into a hooting prance around the room. I was back home in spirit. Hallelujah!

I didn’t sleep at all after the game, and have been pretty giddy all week. Watched a couple condensed replays, and the vivid dissections of the key plays on the Eagles website. Haven’t taken off my Eagle sweatshirt, and strut around town proudly with it on. Peering out at the piles of plowed snow that border the roadways, I do yearn to be out in the backyard in Broomall with brother and dog reenacting the Super Bowl.

The Philadelphia Eagles Cheerleaders parade along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway at 20th Street.

Last Thursday, watching a computer stream of the massive parade, I’m choked up with nostalgia, wanting to be with other sons whose fathers were fans of the team at the time of my birth in Philly, all who’ve made this journey with the city’s football team. Fans from the Northeast, Kensington, Frankford, Point Breeze, Logan, West Philly, Mt. Airy, Germantown, Center City, Fishtown, Fox Chase, Grays Ferry, Olney, South Philly, Oxford Circle, Port Richmond, Roxborough, Overbook Park, Wynnefield, Fairmount, Chinatown, Mayfair, East Falls, Strawberry Mansion, the suburbs, Upper Darby, Havertown, Cheltenham, Merion, Ardmore, Media and all the unique neighborhoods that make up the city and came together for this festival. These fans stuck with the team through all the near-misses, the mediocre and miserable seasons, bad coaches, greedy owners, bust draft picks, and the national pejorative stereotypes about them…and the city. This parade is catharsis. Redemption.

Amid the vitriolic tribalism of this era, each day producing terrifying or outlandish news and bombastic, divisive outbursts from the nation’s leader, there on my computer screen is a wild celebration of a city united by a sports team of all things. Whites, Blacks, Asians, Hispanics, people of divergent faiths, young, old, men, women, children…all as one exclaiming joy to the city’s team…and unto themselves. I’ve always been amazed at the unifying effect of sports. Feels good to bathe in this glory, for at least another few days. Hope the glow lingers. We need it.

You know, Dad, I’ve been thinking. If we hadn’t shoveled that driveway 57 years ago; you were still going to take us to that game. Weren’t you?

Fly.

• • •

Albie Singer, a Philadelphia native and life-long Eagles fan, lives in Glen

Photo courtesy/Albie Singer

Photo courtesy/Albie Singer Source/Wikipedia

Source/Wikipedia Photo courtesy/Albie Singer

Photo courtesy/Albie Singer Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice

Thom Carroll/PhillyVoice